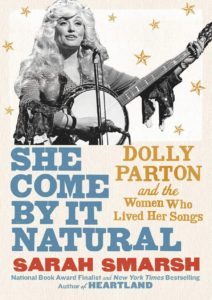

Dolly Parton, 74, has been singing and performing as a self-described “backwoods Barbie” for over half a century. With chart-topping hits such as “Jolene,” “I Will Always Love You,” “Here You Come Again,” and “9 to 5,” Parton has written more than 3,000 songs. She started her own record label, created the Tennessee theme park Dollywood, and frequently donates from her $500 million fortune to treat everything from childhood cancer to Covid-19. She’s even inspired a podcast, Dolly Parton’s America, narrated by the very hip Radiolab’s Jad Abumrad, a Nashville native.

And yet, as Sarah Smarsh points out in her new book, She Come By It Natural: Dolly Parton and the Women Who Lived Her Songs, what Parton is most known for are her improbably sized breasts. Though she also has “a quick mind, a pretty face, [and] a creative genius,” Smarsh writes, Parton became “the punch line of a joke about big tits.” Parton’s surgically augmented and noticeably fake breasts, Smarsh explains, are a strategy to “reclaim not just the joke but the boob itself — as if to make clear, perhaps, that no punch line had caused her to feel shame.”

Throughout her fast-paced and interesting book, Smarsh argues that Parton may have come by her talent “natural,” but she has chosen to perform with hypersexualized femininity to run circles around misogynistic men who continue to control (and shut out women from) country music. Beneath the elaborate blond wigs, layers of makeup, skintight sequined dresses, and relentlessly sunny demeanor, Smarsh writes, lies a media mogul whose deeds align with progressive and feminist politics — though Parton is steadfastly apolitical and refuses to adopt such labels.

Unlike Gloria Steinem and others who have used gender to analyze and celebrate Parton, Smarsh uses the lens of class to examine the country legend’s origins in the impoverished, rural South. She originally published her insights on Parton in 2017 as four separate essays for No Depression: The Quarterly Journal of Roots Music. At the time, Smarsh was also finishing the manuscript for Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth, which she published in 2018.

In the essays and memoir, Smarsh describes growing up poor in Kansas, the daughter and granddaughter of teenage mothers, and coming to know the women who “lived” Parton’s songs. “For these women,” Smarsh writes, “the fight to merely survive is a declaration of equality that could be called ‘feminist.’ But here’s the thing: In my experience, right or wrong, they don’t give a shit what you call it.” Parton’s makeup, clothes, and hair? To Parton and economically disenfranchised women, these “represented not just a life beyond backbreaking labor but also a level of economic agency that might protect a woman from assault.”

Smarsh argues that educated elites likely will miss such undercurrents without an insider’s guide. At some points, her inclusion of personal stories seems insightful; at others, it’s condescending. She reminds readers that her grandmother Betty, who married seven times and eventually earned enough in a government job to provide for Smarsh, understands Parton’s songs as “a nod to women who can’t afford to travel to the march, women working with their bodies while others are tweeting with their fingers.” Less helpful are Smarsh’s overgeneralizations about the educated and wealthy, who, she writes, “tend to regard [poverty] with precious sadness — a demonstration of their own sense of guilt, perhaps, or a lack of understanding about what brings happiness.”

I found Smarsh strongest when she provided close readings of Parton’s song lyrics, especially those from the 1970s, when Parton severed ties to country impresario Porter Wagoner. Wagoner gave Parton her big break, featuring her on his long-running television show, but he also put down her looks and her brains. Smarsh focuses on songs such as “The Bargain Store” and “Down From Dover” to showcase Parton’s gift for telling stories about women with and without power to make decisions about sex and money.

Smarsh brings such analyses back to Parton’s physical appearance throughout the book, describing her performance of femininity as an embrace of the “female divine.” She credits Parton with breaking ground for third-wave feminists long before they were championing “girl stuff.” She notes that when Parton received the Lifetime Achievement Award at the Country Music Awards in 2016, performers included the Chicks and Beyoncé, women who have crossed genres and pushed back against boundaries throughout their careers.

Parton is godmother to singer Miley Cyrus, who raised eyebrows with her overt sexuality with Robin Thicke on “Blurred Lines.” Perhaps Parton’s persistence and successes have also created space for an even younger generation of female singers, some of whom wear baggy clothing to avoid what they call “body shaming.” For the record (pun intended), Billie Eilish, 18, has won five Grammys without so much as revealing a bra strap.