Sarah Anne Johnson’s new novel, The Last Sailor, explores the profoundly personal ways we deal with — or avoid — mourning, and the struggles we go through as we piece our lives and relationships back together after sudden and tragic loss. The story is embedded in the maritime history of 1898 Cape Cod and set in a landscape known intimately to the author since her childhood.

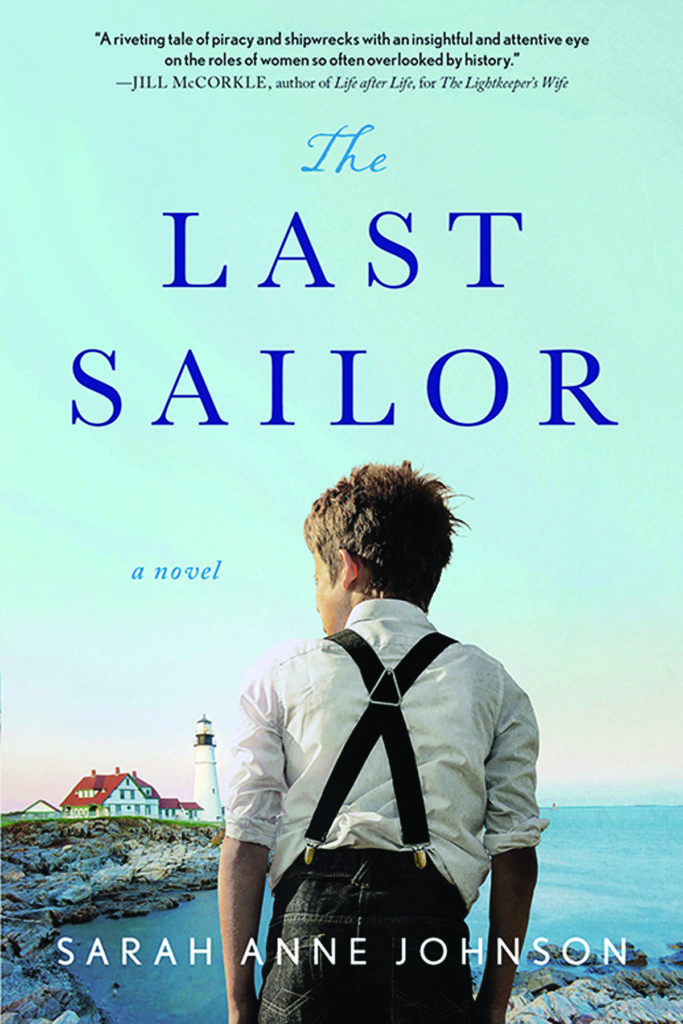

“Loss is a deeply true fact of life,” Johnson says during an interview in her Provincetown home. The Last Sailor, which will be published by Sourcebooks Landmark on Nov. 17, is her second novel; her first, The Lightkeeper’s Wife (2014), is a historical tale of shipwrecks and piracy set in Truro. “Our society does not give us a lot of permission to grieve and does not take into account the layers in time that it takes. I think it’s really hard for people to share their emotions and their loss — to express the depth of what’s going on.” And she notes that this can be particularly true for men.

The Last Sailor opens with the image of a lone man, Nathaniel Boyd, in a small boat on a Cape Cod marsh. “He wanted to be left alone,” Johnson says. “For 10 years, he’d achieved a comfortable solitude on the salt marsh, over two miles from the harbor, until events conspire to bring him back into the orbit of the people he’d once held dear.”

The story was inspired as much by Johnson’s love of literature as her immersion in local history. “In Suttree, by Cormac McCarthy, the first scene is about a man rowing a boat in a river alone,” Johnson says. “I read McCarthy’s descriptions of the water, and it triggered something in me. Reading just those couple of pages in McCarthy’s book gave me permission to see if I could write about this man’s experience, because his solitude spoke to me. I wanted to answer the question: why would someone want be out there alone?”

The reader of The Last Sailor soon learns that Nathaniel is haunted by the death of his youngest brother, Jacob, who drowned in a sailing accident as a child. Nathaniel feels responsible for Jacob’s death, because he had tried to save him but failed. Back ashore, 19-year-old Nathaniel abandons a life filled with plans and the promise of love and disappears into a primal, almost savage existence in the marsh, eschewing all but the most essential human contact. As a result, Nathaniel’s father and brother Finn have to deal with his sudden absence in addition to Jacob’s, and Nathaniel’s young fiancée, Meredith, is plunged into grief as well.

Ten years later, Nathaniel reluctantly agrees to sail a schooner from Boston across the bay to Yarmouth Port with Finn. The tragedy of Jacob’s death is nearly repeated when a young girl they offer passage to, Rachel, slips into the water during a squall — only this time, when Nathaniel dives into the water to save her, he succeeds. Awash in memories of the past, he carries the wounded, unconscious girl to the house nearest the harbor, which happens to be the home Meredith now shares with a husband she does not love.

Nathaniel and Meredith watch over Rachel as she slowly heals. In doing this, they face their longing for a life they believed to be out of their reach after Jacob died. By caring for another person in need, they are able to integrate who they once were with who they have become. As Johnson says, their “transformation is about connection.”

In The Last Sailor, the world of 1898 is effortlessly immediate rather than historical. “I grew up here,” Johnson says. “The book is set in the marsh at the end of my street, Wharf Lane, across the bay from Sandy Neck. I always had a fantasy of living on the marsh. I carry that place within me. I think childhood experiences are so visceral — the smells and the feelings. I can still feel the mud on my feet, so tingly and alive, the briny smell of the air in my nostrils, and the shadows of wind across the grass.”

Johnson’s evocative prose — honed over decades of writing and studying the writing of others — paints details of the landscape of her childhood with a vibrancy that makes this novel about Cape Cod more authentic than most.

After leaving the Cape as a teenager, Johnson returned in 1996 at the age of 32. She lived in Truro for many years before settling in Provincetown. “Provincetown has always been this place where I could find deep respite and silence,” she says. “And I wanted to be in a community of artists and writers.” Her first book took 10 years to write; then she spent six years on The Last Sailor. She’s a believer in endurance. Her mantra: “Writing is all about perseverance, about keeping your ass in the chair.”

Published in the midst of a pandemic that has forced many of us to confront our fear of losing a loved one, The Last Sailor conveys a hopeful message: that our deepest wounds need not define us. Of her characters, Johnson says, “I don’t think they overcome loss as much as go from not being alive to being alive again.”