Jack Boughton, the protagonist of Marilynne Robinson’s much-anticipated novel, Jack, is a thief, a liar, and an alcoholic. He is also exquisitely sensitive, self-deprecatingly funny, and finely attuned to the nuances of spoken and written language. Jack is singular, a beautifully drawn character whose misgivings and inclinations lead him towards tragedy.

Jack is also universal. He is Adam, the Thief on the Cross, and the Prodigal Son. Robinson meditates, through the character of Jack, on knotty Protestant theological problems plaguing Everyman, from predestination to free will. Robinson’s gift is to make the specificity of her characters so interesting and compelling that readers will want to think about hard concepts —especially, in Jack, about grace. Who is worthy of time and patience? Of forgiveness? Of love?

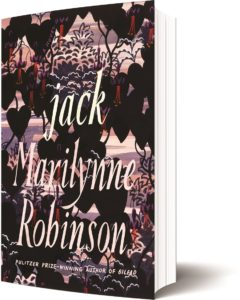

Jack previously appears in a series of three novels by Robinson: the Pulitzer Prize-winning Gilead (2004), Home (2008), and Lila (2014). In these books, Robinson explores conflicts in the families of two white Protestant ministers in Iowa: the Rev. John Ames and his best friend, the Rev. Robert Boughton. Jack, godson of the first and son of the second, impregnates a young woman in Iowa and abandons her. He leaves and then returns home after a 20-year absence, revealing that he has a common-law wife, Della, who is black. The two have a son and are estranged. Beyond these particular details, Jack often serves as a foil in the first three novels. His un-Christian behavior and seemingly terrible choices test the religious convictions of those who know and try to love him.

In this fourth novel, published in September, Robinson turns her full attention and imagination to Jack himself. Where had he gone in that 20-year absence? Robinson has Jack living in a St. Louis boarding house somewhere around 1954, passing time reading in public libraries, hanging out by Eads Bridge, and drinking.

Enter Della, a black high school English teacher from Memphis. She mistakes Jack for a preacher and invites him inside for tea. The joke’s on Della. Jack had bought the suit he’s wearing to appear respectable upon returning home to Iowa for his mother’s funeral. He isn’t a minister. And he doesn’t go to Iowa.

But this isn’t where the book begins. Robinson starts in the middle of many things: the midpoint of her overarching Gilead plot, the middle of St. Louis, the middle of a scene, mid stride, mid conversation, mid ’50s. Here are Jack and Della, mid fight: “He was walking along almost beside her, two steps behind. She did not look back. She said, ‘I’m not talking to you.’ ‘I completely understand.’ ‘If you did completely understand, you wouldn’t be following me.’ ”

Talking and walking and thinking through the middle and muddle take up most of the novel. Some readers — especially if they’ve studied English literature — will take great pleasure in the ways Robinson embroiders lines of poetry, song verses, and passages from the Bible into the fabric of this meandering novel. As Della and Jack wander dreamily through an all-white cemetery over the course of one night, they consider Shakespeare, Milton, Eden, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Protestant hymns.

Later in the novel, Jack turns himself inside out over his desire to give Della a copy of William Carlos Williams’s Paterson, overthinking, as usual, whether it will cause offense. And when, at a pivotal moment, Della considers abandoning her powerful and upright black family for the seemingly worthless white wastrel Jack, she drops off a copy for him of Tribute to the Angels, by boundary-breaking poet H.D., a signal to readers that, against odds and convention, she’ll bestow her love on him.

For those who did not major in English or have not spent time in a church pew, Robinson’s many allusions may feel like obstacles in the way of what little action there is in the novel. These readers may care less for Robinson’s exploration of Christianity, especially the concept of grace — love and forgiveness neither deserved nor even requested — than they do for the specific struggles of these two characters. They will surely be arrested by how Robinson renders human frailty in language, as she does when Jack watches Della slip away into a crowd of white pedestrians, “the path of feckless humankind”: “He stepped into the road, and he saw. The naked man that lived inside his clothes began covering himself with sweat, sticking his shirt to his back. It wasn’t only shame. Yes, it was.”

Jack has so much to be ashamed of. His individual failings defy enumeration. As a white man, he is also guilty of belonging to a population denying humanity and dignity to the woman he loves in a city currently associated with systemic racism. Mid 1950s, there are few places in public they can meet. Della’s neighbors watch “the white man” pine for her on the stoop outside her house. The white desk clerk at Jack’s boarding house threatens to call the police if he catches Della visiting again.

Jack expresses his exasperation as a question: “He said, ‘Look at the life we live, Della. I have to sneak over here in the dark just to steal a few words with you. Is that language, or is it noise?’ ”

Della’s answer shows readers that “stealing words” is a serious and noble business, not at all akin to the thievery usually associated with Jack Boughton: “She said, ‘It’s noise that you have to do it, and language that you do it, anyway.’ She said softly, ‘Maybe poetry.’ ”