Political protest art is not new, as anyone who has seen Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, about an 1830 anti-royalist uprising in France, or Picasso’s Guernica, depicting the merciless bombing by Fascists of a Basque town during the Spanish Civil War, will attest.

Art doesn’t bring truth to power — it brings power to truth. And truth is complex, sometimes enigmatic. We’re more likely to find it in museums than in galleries, which exist to sell art, not to express outrage. Even in progressive Provincetown.

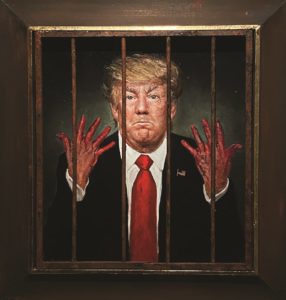

Marla Rice of the Rice Polak Gallery is bucking that trend. She had been offered a painting by Steven Skollar, one of her gallery artists, that depicted Trump with blood literally on his hands, but felt she couldn’t show it in the height of the season. Instead, she decided to show it in the fall. “I wanted to put it in the window before the election, when it would be me making a statement, not just him,” Rice says.

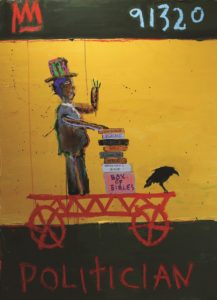

She asked other artists if they’d be part of a show about current crises: Trump’s cruelty and mendaciousness, the suffering caused by the pandemic, and protests against racism and police brutality. The response was strongly supportive, and the result is “Making Waves: Artists Speak Out,” a live and virtual exhibit opening Oct. 16 and on view through Election Day.

“I feel so strongly about social justice,” Rice says. “It allows me to give voice to my own feelings. Artists create art, and I curate shows.”

There are about 80 works in “Making Waves,” by dozens of artists; the Independent caught up with three of them.

Skollar, a native New Yorker and realist painter with consummate old master style, says, “I’ve been obsessed with Trump for years. I grew up seeing this idiot fail upwards. Like De Niro says, he’s a punk. He has cried ‘Fire!’ in a theater. He’s a murderer. I can’t be quiet about this.”

Skollar was diagnosed with pneumonia in January, before testing for Covid was available, and he says he’ll never know for sure if that’s what made him so sick. Early in Trump’s tenure, he painted some lightly satirical paintings that are included in the show, but as the pandemic worsened, his anger took over, and he painted the bloody portrait that inspired the exhibit. “It was somewhat cathartic,” Skollar says. “I’ve never felt like this, and I can’t get over it.”

Wellfleet artist Ellen LeBow contributed a haunting series of Doctor Plague pieces for the show, a character whose origin is in the bubonic plague of the medieval era. “I don’t think I would have taken it up if not for the coronavirus,” she says. “But as an artist, it’s very hard for me to create work that just has to do with the now. It has to show up in the universal somewhere, for me and for people who look at it. I’m more interested in the archetype of the witness, the archetype of the loner, the archetype of the witch doctor.”

Doctor Plague wears a beak-like mask, which was meant to carry protective herbs, but connects to the experience of the Covid pandemic. “All these people are in the hospital dying, and they’re surrounded by people they don’t know wearing these outfits,” LeBow says. “It’s a very lonely way to deal with the healers.”

Willie Little has shown abstract paintings of rusted metal on wood for years at Rice Polak, but for “Making Waves” he contributed a series of assemblages of racist “nodders,” or bobble-heads, that were created as Americana trinkets for white people and made in Japan. Little, who grew up poor, black, gay, and bullied in the rural South, says he was first inspired to create this kind of “in-your-face, reclaimed art” after the shooting death of unarmed Amadou Diallo by New York City police in 1999.

By repurposing racist dolls, Little says he hopes to “reclaim the derogatory and embrace it, thus taking away its power. When slaves were freed, they ate and grew watermelons as a status of freedom, but whites tainted the fruit.” His piece Lady Liberty Realness shows a little girl holding a watermelon slice with cockleburs on her head. These prickly seed pods “sting and hurt,” Little says, “just as it hurt when people mocked us for having nappy hair. I use them on the dolls as crowns of beauty, symbols of black pride.”

For Little, creating these pieces is a way to speak to the racism in America. “To be silent is to be complicit,” he says. “If you aren’t compelled to protest, just don’t be silent.”

Vote of Conscience

The event: “Making Waves: Artists Speak Out,” a group show about “politics, social justice, and the effects of the pandemic”

The time: Friday, Oct. 16, through Nov. 3, Election Day; gallery open weekends

The place: Virtual exhibit at ricepolakgallery.com; in person at Rice Polak Gallery, 430 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free