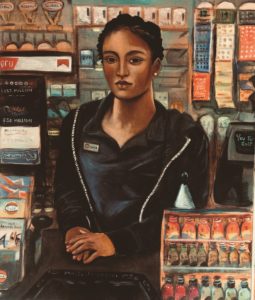

The painter Edith (“Edie”) Vonnegut sits in the sand on Mayo Beach in Wellfleet, gazing at sailboats floating by in the sunshine. Her slender figure and natural beauty defy any guess at her age. “At 70, I have never felt better in my life,” she says. “I’m just getting started, and I finally feel relevant, especially in what I am painting right now: heralding the unheralded, the essential workers.”

Vonnegut, who lives in a renovated barn on family property in Barnstable, stopped to speak with the Independent on her way back from delivering paintings to the Kobalt Gallery in Provincetown for her show, “Essential Frontline Workers 2020,” opening on Friday.

“Edie has given the everyday essential worker their glory day through these portraits,” Kobalt’s owner-director, Francine D’Olimpio, says. “They’re not only masterfully painted but charged with a clear message of the times.”

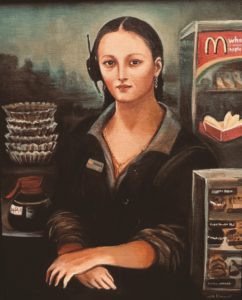

In 2017, Vonnegut embarked on a personal marathon to do a painting a day during the first 100 days of the Trump presidency. One was intended to be a portrait of Ivanka Trump as a McDonald’s worker. “I thought it would make Ivanka more empathetic if she had a minimum-wage job,” Vonnegut says.

She went to McDonald’s to take a photo of a female worker as an Ivanka stand-in but had a change of heart. “I looked at this woman for the first time, and I saw a softness in her face,” Vonnegut says. “She was so sweet and beautiful as she let me take her picture. I thought, I’m not going to cut her head off and put Ivanka’s on it. I’m going to paint her just as she is.”

Vonnegut’s aim to celebrate the unrecognized resonates with aspects of her own life. Born in Schenectady, N.Y., the daughter of writer Kurt Vonnegut Jr. and his high school sweetheart, Jane Marie Cox, Edie spent most of her childhood on Cape Cod. In 1951, when she was two, her father rented a home in Provincetown for the summer and fell in love with Cape life. “There are many photos of me in the water, eating seaweed in Provincetown Harbor,” Vonnegut says, laughing. The family moved here full-time in 1952 — first to Osterville, then, in 1956, to Barnstable Village, where Vonnegut now lives.

“My father wrote his books while my mother took care of everything and kept the quiet for him,” Vonnegut says. “Everyone loved her. It was a fun, free house.” When Slaughterhouse-Five was published in 1969, turning Kurt into a best-selling sensation at 50, he left Cox and moved to New York. “A lot of people don’t take the fame curve very well,” Vonnegut says. “But my mother was never bitter.”

Ten years ago, Vonnegut found a box of 96 love letters written by her father to her mother when he was a young man and World War II soldier. “He kept saying, ‘I’m really not very bright. I don’t know why you believe in me,’ and after he went through the firebombing in Dresden, he wrote, ‘Now, I know what I have to write about, and I can’t do it without you,’ ” Vonnegut says. The letters, edited by Edie, will be published by Random House on Dec. 1 (Love, Kurt: The Vonnegut Love Letters, 1941-1945). “To me, it’s not about him,” Vonnegut says. “It’s about finally putting my mother where she really belongs.”

In her own life, Vonnegut took decades to go public as an artist. It all started when her parents gave her a book on art masterpieces. “I was five, and it was magic,” Vonnegut says. “I knew that I wanted to be a painter.”

When she was 18, Vonnegut spent her first summer away from home, studying with abstract expressionist Irving Marantz. “He was a very nice man, but he wasn’t teaching what I needed,” she says. “All I ever wanted is to paint like Titian or Michelangelo or Raphael. It’s my own little wheelhouse, but it’s enough to sustain me for a lifetime.”

Edie moved to New York City in 1971. “I knew Andy Warhol and all those people, but I never presented myself as an artist,” she says. “I felt people thought that because I was Kurt’s daughter, I was like a cheap souvenir and they weren’t going to give me credit for who I was.”

She returned to Barnstable in 1985 with her second husband, a carpenter and friend from her youth. “When I had my children, I realized that what mothers do is unbelievable,” she says. Many of her works since then depict women in roles denied to them throughout art history, but unlike her essential worker series, they feature angels, mermaids, and cherubs in everyday scenes. “I tend to mess with reality the way Renaissance masters did,” Vonnegut says.

To honor essential workers, she knew she had to play it straight. “That was a shift for me,” she adds. Now that the series, with 15 paintings, is complete, she intends to do more portraits and focus on eco-activist subjects. “I have so much more that I want to say and do,” she says. “I want to be the court painter to common people, to glorify them the way the masters glorified royalty. Marie Antoinette had over 200 portraits painted of her, and she was a useless woman. I’m sick of people thinking they are more important than others. Everyone is beautiful when you look on them with love.”

Pandemic Portraits

The event: Edie Vonnegut, “Essential Frontline Workers 2020”

The time: Friday, Sept. 18, through Oct. 1

The place: Kobalt Gallery, 366 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free; a percentage of sales will be donated to support Cape Cod Covid-19 relief