“I like dramatic, show-stopping images,” says Greg Salvatori. “When I ask you to look at an artwork I created, I want to offer you something that is worthy of your time.”

Salvatori’s captivating photography, which he describes as “playful, uplifting, and provocative,” has found an international following. But behind their bright colors, allure, and technical skill lies a sensitive and thoughtful man who has known intense hardship and trauma and learned to heal through his work. “We all cope in different ways, but when I’m feeling particularly dark and out of sorts, I turn to creating beauty, because there is a life force in beauty,” he says.

Salvatori established his eponymous gallery in Whaler’s Wharf in Provincetown in the summer of 2019, the year he and his husband, writer James Polchin, became year-round residents. “I have lived in many beautiful cities around Europe,” Salvatori says. “Then I moved to New York City and, randomly, one weekend in the summer, found this glorious, phenomenal, unique place, which, to me, beats all other places in the world. In Provincetown, I have everything: the beach, the art community, the LGBTQ community, the friendliness, the liberals, the cute New England look — what else could I possibly want? I could not have imagined this place as a child trying to find his way out of unhappiness.”

As part of his devotion to the town, Salvatori designed and launched the website for the Ptown Gallery Stroll, a group of 35 galleries that banded together to promote the art colony during the pandemic — a time when traditional Friday night gallery openings were largely canceled to avoid crowds.

Born on the border between Italy and France, Salvatori’s childhood and youth were harsh. Following a painful split between his parents when he was very young, Salvatori’s mother joined a religious cult. He broke away at an early age, fleeing abuse at home and bullying at school, and effectively raised himself, taking on various jobs to survive poverty. Instead of allowing these difficulties to break his spirit, he discovered how to live, with evident gusto, a life of gratitude.

“It’s cheesy to say, ‘What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger’ — I believe that what doesn’t kill you should make you think,” Salvatori says. “I realized that every day is a gift, and that life is not necessarily filled with joy. So, when it is, I can’t stop myself from feeling thankful.”

Two of Salvatori’s most recent projects — the photo series “The Clouds,” shot following his father’s death early last year, and the collage series “Moonlight Ptown,” on view at Greg Salvatori Gallery through Sept. 30 — are examples of how he distills beauty from life’s challenges.

Salvatori’s father, with whom he had a strong bond as an adult, suffered from Alzheimer’s. It is not difficult, in Salvatori’s “Clouds” photographs of male faces disappearing into steam, to see an evocation of a loved one’s mind gradually dissolving in front of your eyes.

“My father was a journalist and a marvelous storyteller,” Salvatori says. “When he passed, I had the idea to collect a large number of artists and other creatives from Provincetown and to populate an imaginary heaven with all these interesting people for my father to interview, so that he could tell their stories. It was a way for me to reconcile myself with the fact that he was gone, but also to realize that he is still here within me, and within my art.”

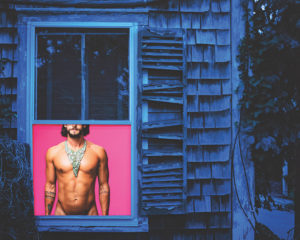

“Moonlight Ptown,” Salvatori says, came together as Covid-19 shut down the world. Salvatori biked through Provincetown, taking hundreds of images of windows and portholes. “Many photographers this year were taking ‘pandemic portraits,’ photos of people in their windows, as a way of documenting what was happening,” he says. But to populate his windows, Salvatori chose images that are vibrant and sexy from his “vault” of hundreds of thousands of photographs. “My pandemic portraits leave the pandemic behind and go into a dreamland where everything is as far as possible from the gray reality we are living in now,” he says.

Using the concept of a doll’s house into which the viewer — or voyeur — can peer, Salvatori created three-dimensional, layered collages of images to create the illusion of gazing into another person’s home. He sets up a contrast between the strength and beauty of male models’ bodies and “the fragility of the architecture of the old wooden houses with peeling paint.”

In saturated shades of blue and pink, Salvatori creates a mood of mysterious, moonlit streets. “I start from an image in my mind, a dream or a vision. Then, the process of trying to create this vision leads you to a new image that surprises you. Art, to me, is really about the journey, which, if you’re humble enough, can be open. You think you know where you are going, but then, you find yourself discovering a new land that is more beautiful than anything you could have envisioned.”

Salvatori’s “Moonlight Ptown” series is also an ode to his new home. One collage, Moored, in which a nude model has his arms tied behind his back through a window, suggests a sense of captivity. Salvatori, however, says he intended something quite different. “To me, this image is about the feeling of safe haven Provincetown gives me,” he says. “Instead of tying you down, the ropes are keeping you from drowning in the storm that is raging outside.”