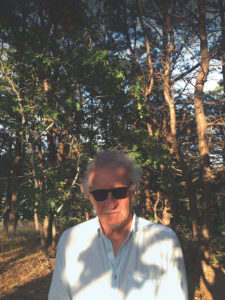

“I loved the darkroom, but the world changes,” photographer Francis Olschafskie says, a light wind scattering his raspy voice. “These prints were sort of an end for me.” Olschafskie, whose work using vintage negatives is currently part of an exhibit at the Schoolhouse Gallery in Provincetown, is seated on the wooden deck of the Truro home he shares with sculptor Anna Poor; their secluded hillside retreat was built by Poor’s artist family. “At night, looking toward Provincetown,” Olschafskie says, “the sky sparkles like a diamond necklace.”

Olschafskie grew up in a northern Connecticut farming community, and was drawn to magazines such as Life, where the world was photo-documented in iconic black and white. “Those pictures,” he says, “made me want to be a photographer.” Early on, he had his own camera and built a basement darkroom. His family urged him to study business, but the pull toward art was strong. By the time Olschafskie was drafted to serve in Vietnam, he’d done enough professional work to list his occupation as “photographer.”

He and Poor met in the mid-1970s as undergraduates at MassArt in Boston. He was impressed with a piece in a campus sculpture show, asked to meet its maker, and was surprised when Poor came over to say hello. She had signed her piece “A. Poor,” and Olschafskie assumed the artist was male. Not long after, Poor suggested he visit her in Truro. “It took six hours to find the house,” he says with a laugh. “A few hours from Boston, and the rest navigating Truro roads.”

Olschafskie showed his work for decades in New York City and Europe before it appeared on the Outer Cape. His Provincetown affiliation began at artStrand, an artist-run cooperative that flourished for a decade beginning in 2005. Poor, a founding member, encouraged him to join. Today, both show at the Schoolhouse.

Much of Olschafskie’s work is color photography, and the complex perspective of these images cause the eye to jump back and forth between layers of form and color. Some see this work as abstract, but not Olschafskie. “It has nothing to do with abstraction, and has everything to do with reality,” he says. “I call it hyperrealism.”

In capturing the shifting panorama of urban life, Olschafskie’s color images appear to nod to ’80s street photography, but his process is more studied. For him, getting to a decisive moment while shooting on the street involves patience and enduring occasional harassment: he stands outside a promising exterior and waits.

This afternoon, though, what’s on his mind is far from the potential of color to capture the buzz of urban life. He’s focused on the stillness of black and white, and his own journey as photographer and inventor, wrapped around the history of photography.

In the mid-1980s, Olschafskie says, “I came across these 8-by-10 glass plate negatives in a box, created in 1929.” The unexpected cache, abandoned by a portrait studio, was stored outside Boston. A friend who knew of his interest in the history of photography and his darkroom skills invited Olschafskie to look around.

“I took a batch and made pictures,” he says. The result was the suite of silvery prints, his “Glass Series,” now on view at the Schoolhouse.

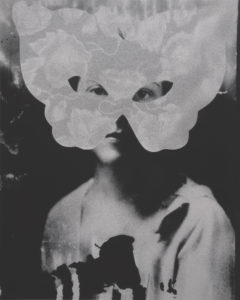

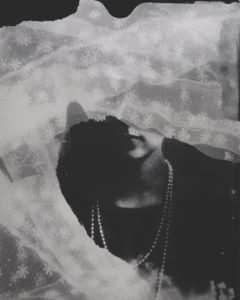

It was a challenging process: he put each glass plate negative on light-sensitive paper and layered it with a unique masking object, often see-through, such as a curtain from his home. The altered negative was exposed briefly to light before being developed in a chemical bath, a process that combines the exposure of a camera-less photogram with straightforward printmaking. “It’s understanding photography, the history of the medium, and understanding light,” Olschafskie says of this project.

Olschafskie was a pioneer of the technology of digital color photography as a graduate student at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but his love for the darkroom and vintage photographs is still palpable.

When the glass plates were originally shot in the late 1920s, surrealism was coming into its own, and their anonymous images, printed with Olschafskie’s surface additions, suggest a noir, surrealist aesthetic. In one, the face of a woman wearing pearls is partially obscured by fabric, her Mona Lisa smile flirting with the camera. In another, a face teases the viewer from under a floating catlike mask.

Olschafskie’s prints arrive at just the right moment, when masking is an act coded with meaning and politics. Exposed in his darkroom three decades ago, from glass plates made by an anonymous artist five decades before that, these images owe their existence to a collaboration that crosses a century of photographic history.

“This work,” Olschafskie says, “reflects the aesthetic idealism that I had, and still do, of what photography is, and how important it is to our world.”

Glass Menagerie

The event: Exhibit of “Glass Series” silver gelatin prints by Francis Olschafskie, part of a group show with Mark Adams, Rebecca Doughty, Ellen Rich, Jason Rohlf, and Frankie Rice

The time: Through Aug. 31; open daily except Tuesday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., Friday and Saturday till 6 p.m.; appointments at calendly.com/schoolhousegallery

The place: Schoolhouse Gallery, 494 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free