Painter Christopher Sousa, whose exhibit, “All the Time in the World,” will be at William Scott Gallery from Friday, Aug. 7,

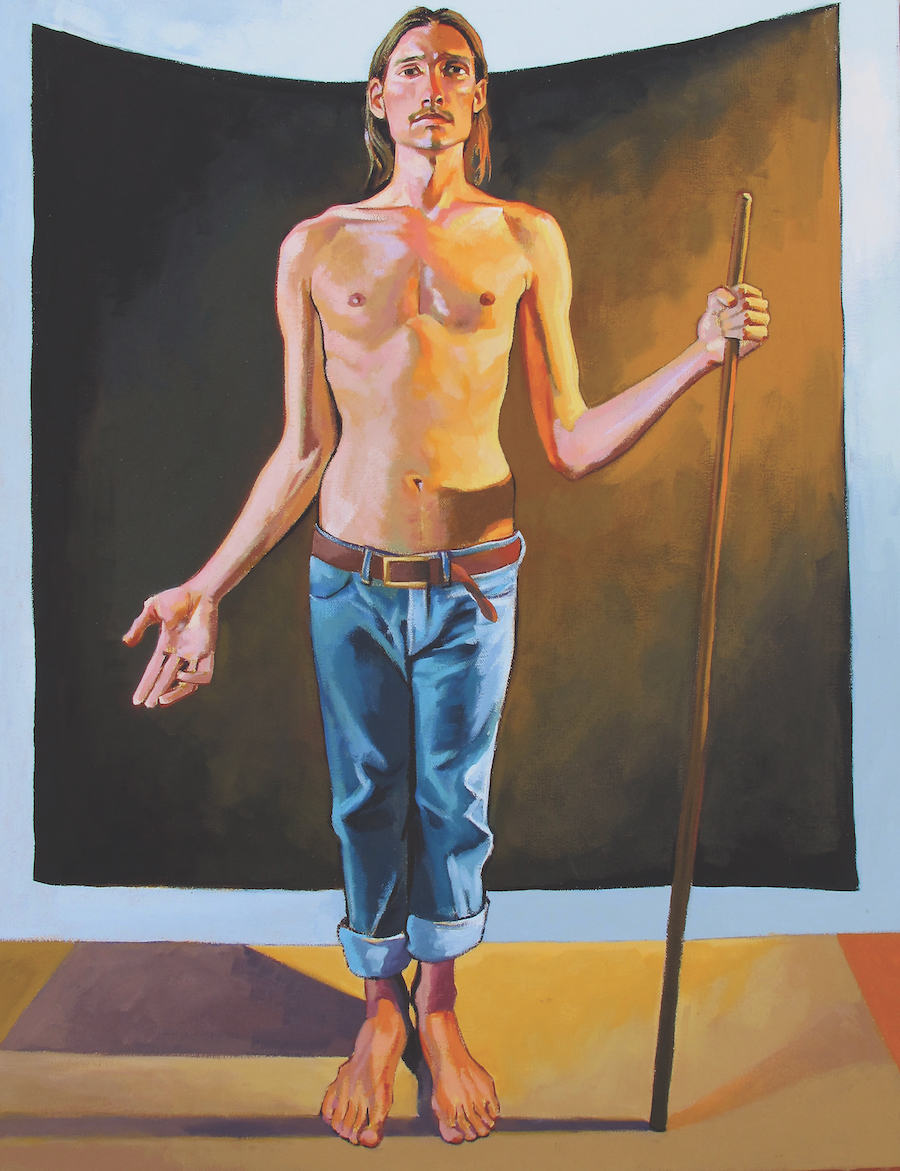

through Aug. 19, does not paint what he considers gay stereotypes: macho, leather-clad, Tom of Finland-type motorcycle men. In his male portraits, he’s interested in depicting “a softness and beauty traditionally associated with portraiture of the female,” he writes in his artist statement. Sousa’s work, first and foremost, is personal, intimate, and contemplative.

“As much as I love and appreciate a lot of queer art, there’s not a lot of it that depicts my experience as a gay person,” he says. “I just want to give my point of view, which is different.”

The 52-year-old Sousa was born in Fall River, the second of four children. “My first memory is that I always wanted to do whatever my older sister was doing, and she liked to draw,” he says. “I found I had natural talent. In school, I got a lot of attention for it. I wasn’t a great student, so I appreciated the positive feedback from my art teacher and kids who would tell me I was cool because I could draw.”

Despite the attention he received, Sousa’s post-high-school landscape was an empty canvas. He wasn’t interested in college, but, at the urging of his family, he enrolled at a local community college anyway. Art was still his only interest, but the school emphasized commercial art, without a shred of creativity, so he dropped out after a semester. His life became a series of meaningless jobs just to pay the bills. He was commuting an hour each way to a job silk-screening highway signs when the airliners crashed into the twin towers. That’s when he heard Provincetown calling him.

“After 9/11, I thought, what am I doing with my life, what do I really want to do?” This coincided with a breakup with a boyfriend with whom Sousa had once spent a summer in Provincetown. “We had always kicked around the idea of eventually moving here together,” he says.

Sousa had been visiting Provincetown since he was a child. “It was a place my parents took us for day trips,” he says. As he grew older and realized that he was gay, he came even more, feeling that the locals were his people. “After 9/11, I wanted to start everything over, so I quit my job, got rid of everything I owned, and said, ‘I’m moving to P’town and learning to paint.’”

He was 35 years old and almost entirely unschooled in painting. The one real class he had taken was a semester at the Art Students League of New York when a friend had lent him his New York apartment.

Some artists follow the royal road to artistic fame — attending a prestigious school, followed by graduate degrees and residencies. It’s the unfortunate truth that some collectors won’t buy a painting before seeing credentials that assure them the artist is any good.

And then there are mavericks such as Sousa, who came to Provincetown and put in the time and diligence, teaching himself things like how to mix color, how painting actually works. Part of him is glad he never had any formal training. His technique slowly improved from taking an occasional class from a local artist, or from friendly advice from a fellow painter or studio mate. “I always wanted to paint my way,” he says.

He chooses his subjects because there is something about them that he finds physically interesting. They aren’t archetypes — they are people Sousa knows. “I see someone who fascinates me visually,” he says. “It’s important for me to capture what I feel is the essence of the person.”

If they agree to sit, Sousa invites models to his studio, where he takes between 800 and 1,000 digital photographs of them. His personal visual language is strong and unmistakable — you’ll always be able to spot a Sousa portrait in a room. The sitter, male, identifiable, not abstracted, almost always partially dressed, is a vertical, either facing forward or three-quarters, and lit by strong side lighting. The lighting separates the sitter from a background that’s either rectangular or circular — Sousa never disguises the fact that it might be a sheet tacked to a wall. His palette is bright and luminous. Odd, obscure props, coupled with equally obscure titles that usually reference song lyrics, finish the work.

Through his painting, he understands what fascinated him in the first place. “Ninety-nine percent of the people I paint I feel are particularly beautiful,” he says. “But I’m not trying to sexualize the subject.” That’s what makes Sousa’s paintings so refreshing. It’s not about sex and come-hither poses. It’s about a particular person’s somewhat wide hips and big feet. And that can be particularly beautiful, indeed.