Even before her mother, Michele Antoinette Pray-Griffiths, died in the summer of 2014, writer-photographer Rachel Eliza Griffiths was shooting black-and-white self-portraits, positioning herself in locations that resonate with history, memory, and anguish. She calls the resulting portfolio daughter: lyric: landscape, and in the preface to her new book of poems and photographs, Seeing the Body, she writes that the images “function as a map of the self and the greater world in which I am both visualized and invisible, as a symptom of grief and identity.”

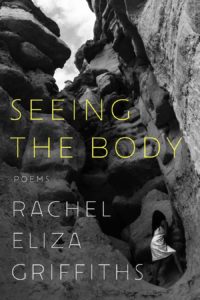

The cover shot of the book suggests the scenic images of Henry Fox Talbot, though from a feminist vantage point. Griffiths, interacting with the Southwestern landscape, her white shift signaling vulnerability, attempts a risky ascent from the base of a soaring, nest-like rock formation. “It was like being inside the body of the Earth,” she says, speaking from her home in New York City. “I was sweating and shaking.”

In another striking image, shot in Mississippi on the side of a road, bordered by a tobacco field, “The Southern dirt is the symbolic image of this country,” she says. “Dancing barefoot as I was, I felt the presence of so many people who worked that field, and why that field is there.”

Poems in Seeing the Body connect to this haunting presence. “The tree/ trying, alone, to survive our dead/ names in the stripped bark,” Griffiths writes in “Whipping Tree.”

Seeing the Body was published by W.W. Norton & Co. in June, after the pandemic drove a retreat into interior spaces. Griffiths herself dealt with Covid-19 in late winter, and, until recently, has remained at home. Her original warm-weather plans included a three-week residency in Italy and an August visit to Provincetown, where she has an enduring connection to the artistic community. The book’s virtual launch was presented by New York City’s Center for Fiction. Other recent virtual readings paired Griffiths with such Fine Arts Work Center colleagues as the poets Marie Howe, Reginald Dwayne Betts, and Nick Flynn.

Griffiths discovered Provincetown two decades ago, around the time she was completing a master’s in fiction at Sarah Lawrence College. The Fine Arts Work Center awarded her several summer scholarships to study fiction and poetry. “I had never been to the Cape,” she says. “The town and the work center welcomed me. I felt like I was home. The energy, the gardens, the smell of the water, the art galleries, the inclusivity of queer and gay and trans and lesbian individuals, all of that was really beautiful to me. I was in my 20s and had found my place, where I could be all of my different selves.”

Griffiths has since returned to FAWC as an instructor. Her mixed-media workshops combine, like Seeing the Body, writing and image-making. Teaching or not, Griffiths often returns to Provincetown, especially enjoying winter’s calmer pace.

About finding her reading voice, she says, “In the beginning, it was, ‘This is how I use my body to read my work: I don’t want to overthink it.’ I like to read aloud. The feeling of sharing, in that way, is a very old thing in me. It is as though I am meeting the language again.”

The pandemic altered that. “Recently, having to read alone to a computer screen, I do think about my voice and try to assure myself that I am not in a room by myself,” Griffiths says. “I try to fill the room with living people I know and love, and also the presence of people beloved to me who are no longer here.”

The poem “Comedy,” originally published in The New Yorker, is set in a hospital room. Griffiths, visiting her mother, sets the stage with plain speech: “I am here before the nurse brings my mother breakfast.” The tone shifts to visions of her mother’s passing: “This is my mother who flew away/ from my grasp in the tunnel without end.” As in cinema, the misty dreamscape dissolves and we return to the bedside visit. The poem ends with her mother’s resigned directive: “Yeah don’t go write about me like that./ I already know you will.”

The impending separation and its aftermath are presented as an epiphany. “I don’t pretend to know her thoughts,” Griffith says. “She has her own agency. Although I am not at peace with grieving her and missing her, I feel the daughter and the artist are at peace within me, and this is really significant to how the book came to be. While there is a loss and an immediacy of pain in Seeing the Body, I also tried to show the powerful things about her, the kind things about her, the salty and sweet things about her.”

While she speaks, Griffith is packing cameras, tripod, and writing materials for a stay in a heavily wooded area upstate. The plan is to create a new set of images, and work on her first novel. Is there a theme? “Not yet,” she says. “I kind of like it to stay messy. I don’t know yet what it is or where it wants to go.”

Griffiths pauses, a smile in her voice. “There is no book before, and there may not be a book after, but I am excited to be caught up in this new space.”