If you’re a baseball fan, William Ciccariello’s paintings of players will soar like a home run sailing over the Green Monster, up into the light and then gone, into the dark of night.

This series of small portraits of great players from baseball’s golden era, part of a group show at Rice Polak Gallery in Provincetown through Aug. 5, transcends the familiar historical art of baseball, because Ciccariello isn’t actually concerned about depicting the players themselves. In these paintings, as in his other work, with such subjects as shipwrecks, soldiers, and still lifes, what he’s interested in is time. Specifically, he’s concerned with what time does to our heroes: our athletes, majestic sailing vessels, warriors, and, by extension, us, when time overtakes us all.

“I’ve always been concerned with time, how long things take and what the passage means,” Ciccariello says. “All of these subjects are dead and gone. I think everyone feels time has a precariousness to it, because it’s your life.”

He was born in 1954 and raised in Port Washington, N.Y., on the North Shore of Long Island, what Ciccariello calls a “really nice, sleepy town.” His father repaired jewelry in New York City, and his mother worked from home for Publishers Clearing House, later getting her degree in library science and becoming the town’s librarian. With six brothers, it was a busy household. It also was one filled with paintings. Ciccariello’s grandmother, who died five years before he was born, was an artist who studied with Hans Hofmann in France, and whose work in the 1930s morphed into social realism.

“She was a serious painter, but never had any recognition or notoriety,” Ciccariello says. “It made such a strong impression on me that someone you did not know could leave so much behind for people to look at.” It seems that, even as a child, Ciccariello was noticing time and history and art, and the dimensions they occupy.

He was shy as a child, and art became his way to discover the world on his terms. The young artist displayed natural talent, and when it came time for serious study, he enrolled at a state university that offered a respectable art program. But it wasn’t enough of a challenge for him, so Ciccariello transferred to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where he finished his training.

He has worked as a fine arts painter his entire adult life, developing a mature body of work, never wanting or needing to dip a toe into the commercial world. “The ideas and feelings I address in my painting are ones of fragility, balance, precariousness, decay and ruin, permanence, and the transitory quality of time,” he says. “I like to impart some hard effort to make them worthy of memory and merit.”

Ciccariello’s process begins with the imagery. “Many historical images are compositionally arresting and are of an era that’s long gone,” he says. “I like trying to portray that.”

First, he traces a photograph on a piece of Mylar. He then coats the back of the Mylar with charcoal, in essence turning the Mylar into something like carbon paper. Placing the Mylar over the board, he retraces the image, transferring it in charcoal onto the board. “It’s an old-school method,” Ciccariello said. “There are other ways of projecting images, but I don’t think like that. I like the methodical process of doing it by hand.”

What’s left behind is a clear piece of Mylar with a tracing on it that Ciccariello sometimes will then paint (some examples are at Rice Polak). “They have kind of a ghostly look about them, because they’re grayed out, and I find them really interesting.”

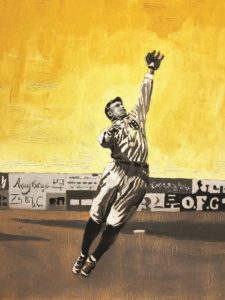

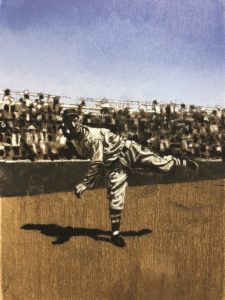

Ciccariello reduces the found images he uses to a simple set of elements that he balances against backgrounds of two sets of complementary colors. This goes beyond representational art — the effect is a visual impression of light and space that belongs to Ciccariello alone.

The painting Lefty Grove is a good example. The unexpected comparison of the blue or blue-violet at the top and the dark sepia at the bottom is how Ciccariello conveys his concept — his idea — of time: colors have shifted and faded, like they do on old photographic color film. The strong, fat diagonal of the fan-filled bleachers that presses down to the left is brought back up by the lever of Grove’s body, his hip the fulcrum, his gaze at the viewer the locus of the painting.

By incorporating conceptual elements, such as archival photography, along with his meticulous brushwork, subdued palette, and tight compositions that ground the paintings into their own liminal spaces, Ciccariello presents heroes who we all recognize, and who are calling to us from another era.

Diamonds Are Forever

The event: Exhibit of artwork by William Ciccariello, part of a group show with Nick Patten, Sean Thomas, and Robin Winfield

The time: Thursday, July 23, through Aug. 5; gallery hours, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily, and Friday-Saturday evenings

The place: Rice Polak Gallery, 430 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free