In 1972, James Baldwin wrote “The Shot That Echoes Still,” a painful and personal essay for Esquire magazine reflecting on the assassinations of Malcolm X in 1965 and Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. Baldwin asserted that the two giants of the black power and civil rights movements, respectively, had begun “at what seemed to be very different points,” but “by the time each met his death, there was practically no difference between them.”

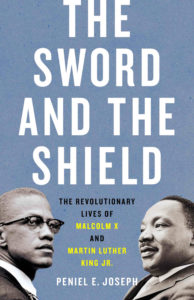

Many historians have, in excellent works too many to number, thoroughly evaluated Baldwin’s observation of the narrowing between Malcolm’s and King’s tactics and visions. With The Sword and the Shield, Peniel Joseph returns to Baldwin’s claim. Joseph, a professor of history, holds the Barbara Jordan chair in political values and ethics at the L.B.J. School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas Austin.

He is more than up to the challenge. Joseph has spent two decades thinking about the intersections of race, power, and social change, having written the lively Waiting ’til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America and accessible biographies of Stokely Carmichael and Barack Obama.

In his latest book, Joseph offers “a new interpretation” of these two 20th-century titans by considering them together and by the metaphors of Malcolm as sword, King as shield. Joseph describes the men’s advocacy and activism as having transformed “the aesthetics of American democracy,” a fine phrase that is nonetheless hard to parse. If, in passages such as these, Joseph works too hard to make big claims, he more than redeems himself by using his masterful knowledge of the material to provide a riveting inspection of these two men’s intellectual and political trajectories.

The first two chapters of The Sword and the Shield borrow heavily from previously published biographies and, though important, are in some ways the book’s weakest.

In the first chapter, Joseph provides Malcolm’s origin story: the early years in Detroit as the child of poor wage workers devoted to Marcus Garvey’s teachings. He focuses on Malcolm’s imprisonment in Connecticut, his self-education and radicalization as he joined the Nation of Islam (NOI) and emerged as an NOI minister and respected acolyte of leader Elijah Muhammad. The chapter ends with Malcolm’s exposure in 1955 to the Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung, Indonesia, which convinced him that American blacks needed to find solidarity with global post-colonial struggles. Joseph refers to Malcolm’s belief in black power and unity, and his rejection of integration, as “radical black dignity.”

King, Joseph explains in the second chapter, was born into Atlanta’s black elite, which was made up of “big Negroes” — college-educated professionals and entrepreneurs. His father was the highest-paid black minister in Atlanta. After earning an undergraduate degree at Morehouse College, King was drawn to the ministry, studying at Crozer Theological Seminary and eventually Boston University, where he earned a Ph.D. At Crozer, King encountered a Christianity whose appeal was rational and political, worlds away from the emotional experiences of faith in his father’s Atlanta congregation. He finished at B.U. and married Coretta Scott. The two moved to Montgomery, Ala., just as activists engaged in a 381-day-long bus boycott. It was there that King learned the nuts and bolts of grassroots organizing, devoting himself to what Joseph calls “radical black citizenship,” an unshakable belief in the principles of democracy and the use of nonviolent civil disobedience to bring about change.

But even as they laid out seemingly opposite stances, the distance between Malcolm and King was never as great as many assumed. While Malcolm was considering the implications of Bandung, King read Gandhi and Marx and visited Ghana to celebrate colonial independence with Kwame Nkrumah. In a sermon he delivered to 12,000 listeners in New York in 1956, King compared Exodus with the worldwide struggle for freedom from “colonial powers seeking to maintain their domination.” Joseph notes that this line “might have made Malcolm X proud.”

It is in such points and counterpoints that Joseph’s scholarship and writing shine. He knows how to pluck nuggets from Malcolm’s and King’s speeches to great effect, providing context each step of the way. He shows that the media and historians have overlooked the more radical aspects of King’s speeches, while he lets Malcolm’s zingers stand.

For example, when King expressed pride in activists’ ability to desegregate Southern spaces, Joseph shows Malcolm countering that any “Negro trying to integrate is actually admitting his inferiority, because he is also admitting that he wants to become part of a ‘superior’ society.” King led crowds on marches through Detroit and Washington, D.C., and Malcolm responded by calling the Constitution’s 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments “hypocrisy” and compared the demonstrations to sporting events such as the Rose Bowl and World Series.

“While King was having a dream,” Malcolm said, “the rest of us Negroes are having a nightmare.”

With time, Malcolm cooled his rhetoric and embraced the possibility of working with whites. And King, especially after Malcolm’s death, and as the Vietnam War accelerated, challenged the status quo with increasing rage. He described blacks as “living in the basement of the Great Society” and noted “the cruel irony of watching Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools.”

Joseph notes in his epilogue the names of those whom police have recently murdered, from Sandra Bland to Michael Brown, and the birth of the Black Lives Matter movement. It’s clear that both King and Malcolm would have anticipated these killings (and George Floyd’s). Whether one would have responded as a sword and the other a shield is ultimately less interesting or important than having been helped to appreciate that they both — had they been allowed to live — would have served not just as spokesmen but as statesmen.