Visiting the Rice Polak Gallery in Provincetown after three months without live art is a surreal experience, from being presented with hand sanitizer and plastic gloves at the door to being allowed to touch (yes, touch!) Anne Lilly’s kinetic sculpture Calendar for Parmenides.

This stainless-steel artwork is set in motion by a human agent. Gears turning, a minimalist hourglass rotates inside a circle so perfectly that the pieces look as if they might converge. Descriptions, photographs, even videos, don’t do it justice — it must be experienced firsthand.

Calendar for Parmenides is one of the works by Lilly on view from July 9 through 22 at Rice Polak, part of a group show that includes art by Ellen LeBow, Julie Levesque, and Connie Saems. The exhibit offers a few of Lilly’s sculptures, but it mostly features her more recent watercolors.

Lilly’s life trajectory seems to consist of several shifts: from the West to the Northeast, from engineering to architecture, from architecture to art, from the three-dimensional realm to the two-dimensional.

“I grew up out West — not the Midwest, but the wild West,” Lilly says. “Oklahoma, Wyoming, Idaho, Colorado. But I was magnetized by the Northeast at a very early age.”

After studying engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y., for one year, she transferred to Virginia Tech to study architecture. Upon graduating, she worked in London and Switzerland before moving to Boston. But being in an architecture firm felt constraining.

“I had ideas that were just never going to find their way into an architecture practice,” Lilly says. Those ideas were about movement, three-dimensionality, and the threshold between being and not being.

She got a studio and took classes in metalworking at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and MassArt. Around 2000, she struck out on her own as an artist, and, until recently, made kinetic sculptures crafted in steel.

Eventually, the urge to shift arose again. Lilly noticed that when she would travel with her husband, Joel Janowitz, a painter represented by Schoolhouse Gallery in Provincetown, he was able to work on the road. “I was just twiddling my thumbs,” she says. Merely thinking about sculpture, an intrinsically hands-on activity, is not always productive.

She also increasingly found her machine shop practice, which consisted of meticulously preparing parts, to be confining. “It felt like I didn’t need those rules anymore,” Lilly says. And due to the tangible nature of her work, she was always making repairs. “I recognized that I needed to find a different way of engaging people’s sense of touch than their literal sense of touch.”

She gave up her shop and works mostly with watercolors now. She says that if she returns to sculpture, “it’s going to be with very different materials.” Her two-dimensional works, however, explore similar themes as her three-dimensional ones.

“Intuitively, I was looking for a way for there to be movement without mass, and with as little form as possible,” Lilly says. “On paper, you can really move into that threshold very effectively.” Her works explore “systems of geometry that aren’t rigid but bounce your eye around in a way that is lively and not just deadly ordered.”

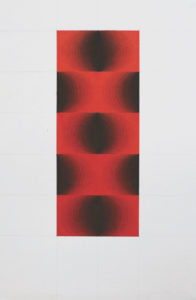

For example, Lucio, one of the watercolors in the Rice Polak show, uses gradients of color to create the illusion of motion. “I realized I could set a palette that was incredibly simple, not dealing immediately with issues of color or tone, and make things come into being, either vanishing or materializing,” the artist says.

Lilly says her painterly practice, which consists of careful measurements and labeling, is influenced by her architecture training. “I think it’s almost a liability,” she says. “Sometimes it’s hard for me to let go and just be direct and spontaneous and free and intuitive.”

The medium, in some ways, helps her. Watercolor is inherently uncontrollable: it runs, it wells up, it soaks through the paper. Unlike oils, it cannot be revised or wiped away. “My husband, Joel, quotes John Singer Sargent as saying, ‘Watercolor is making the most of an emergency.’ ”

In Tide Chart, Lilly overlays red and cyan paint to create an undulating grid that is structured yet not fully tamed, like the sea itself.

She has also begun experimenting with bright colors. A couple of months ago, she was walking to her studio, and azaleas were in bloom. “I stopped to look at them, shocked,” Lilly says. “How is such an intense color possible? Nature is so bold.”

When she got back to her studio, she felt underwhelmed by her work. “I mixed up the most outrageous orange I could and did this really bold wash over the watercolor,” she says. “It was instantly something different and much better. The original rules were still there but disguised in a mysterious way.”

This is the case with Poppy, also on view at Rice Polak. Like Lucio, it possesses a sense of motion, this time in bright red.

Though Lilly’s transition from sculpture to works on paper ran parallel to the pandemic, she says it wasn’t a reaction to it. But in her two-dimensional works, she is able to create a similar sense of touch, of causal motion, that is present in her sculptures. In a time when touch is potentially dangerous, the effect is profound.