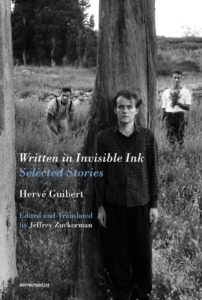

In the introduction to Written in Invisible Ink: Selected Stories, by Hervé Guibert, the late queer literary hero of the AIDS era, translator Jeffrey Zuckerman writes that in French, “invisible ink,” or encre sympathique, connotes not just concealment, but closeness.

The notion of “invisible ink” reappears in these stories that Zuckerman has gathered and translated for the first time into English. (Dating from between 1975 and 1988, they had previously been published separately, and only in French. The newly translated collection was published by Semiotext(e) in May.)

Most strikingly, the phrase appears in “A Trip to Brussels,” in which the author’s excursion with an anonymous young man breeds deep familiarity and intimacy, though they never meet again: “The words we spoke made an apocryphal story that was perfect: faded, singed, written in invisible ink, buried and unexhumable. Nothing could reconstruct these words, they were like a treasure in the depths: intimidating, undetectable.”

It also appears in “For P.: Dedication in Invisible Ink,” which tells of the relationship between a ghostwriter and his older mentor that is filled with as much resentment as admiration. The concept of words unearthed or exhumed also appears in other stories in the collection, such as “A Posthumous Novel” and “A Man’s Secrets.”

Guibert’s work will be read and discussed via Zoom by Zuckerman and renowned author Edmund White, in a virtual interactive event hosted by East End Books Ptown next Wednesday, July 15.

White wrote the afterword to a new translation of Guibert’s To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, also published by Semiotext(e). That book is perhaps Guibert’s best-known work. In it, he documents with shocking detachment his body’s ravaging by AIDS, and reveals that his friend Michel Foucault, the influential philosopher, was likewise infected with HIV. Guibert died in 1991 at age 36.

A master of “autofiction,” his brand of autobiography and imagination, Guibert was also a photographer — a sensibility that is evident in the story “Personal Effects,” a series of descriptions of sinister objects — and a journalist, an experience he draws on in the story “Obituary.”

Zuckerman triumphs at translating Guibert’s long, sinuous sentences into the comparatively clunky English language — no easy task. “French and Italian are both very musical languages,” Zuckerman says by email. “In English, we notice when something is musical, because that’s the exception rather than the norm, whereas in French and Italian, it’s when something isn’t musical that it stands out.”

Zuckerman, who is deaf, says that he picked up French “bizarrely easily” in middle school. “Maybe [it’s] because I didn’t learn to talk until I went to a school for the deaf and had to learn to do so systematically, not organically … picking up another language in the same way some years later was something my brain was wired for.”

The works in Written in Invisible Ink, bordering on undiscovered, trace the writer’s development in sometimes unsettling ways. The earliest works, “Propaganda Death” and “Propaganda Death No. 0,” which were written between 1975 and 1977 when Guibert was in his early 20s, reveal that his preoccupations with body horror and necrophilia far predated his illness.

“Most readers, myself included, know about Guibert from the books at the very end of his life,” says Zuckerman. “So, it was a real shock to … realize that his late style belied the viscerality of his earliest output.” Indeed, the early stories are so explicit and utterly “off-putting” that Zuckerman considered placing the first book in the appendix, so as not to “scare off brand-new readers.”

Nonetheless, Guibert’s “early work lays out all his obsessions and fascinations; it’s almost a road map,” Zuckerman says. “So, I had to put it in front for the sake of chronology and for all the readers who’d come to this volume for a sense of how Guibert’s style and themes developed over the course of his short career.”

For those who don’t mind reading out of order, Zuckerman says his favorite stories are “Posthumous Novel,” “A Kiss for Samuel,” “The Trip to Brussels,” “Mauve the Virgin,” “A Man’s Secrets,” and “Flash Paper.”

Zuckerman writes in his introduction that the act of exhuming Guibert’s corpus can be exhausting. This metaphor for the role of the translator, though apt, can be thought of in another way, especially relevant to this book. The translator, like a catalyst, renders Guibert’s words visible, decoded, and able to be placed in relation to the whole of who he was as an artist.

Missing Ink

The event: Reading and discussion on Written in Invisible Ink: Selected Stories, by Hervé Guibert, with translator Jeffrey Zuckerman and author Edmund White

The time: Wednesday, July 15, at 5 p.m.

The place: eastendbooksptown.com via Zoom; pre-registration required at Eventbrite.com

The cost: Free