The history of the gay liberation movement is usually told from the point of view of those at the center of the action, from the Mattachine Society and Daughters of Bilitis to the Stonewall Riots in Greenwich Village to the various political battles that ensued. The setting is invariably an urban area — New York City or San Francisco — with a dense homosexual population and subculture.

Yet queer people are everywhere, and their stories and struggles are everywhere, too. In some ways, the LGBTQ pioneers who created communities and support systems where there were none, and where hostility was strongest, have the most interesting stories of all.

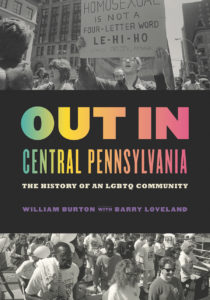

That’s what William Burton discovered in writing Out in Central Pennsylvania: The History of an LGBTQ Community, for which he’ll do a virtual reading and talk via East End Books Ptown on Saturday. Burton, a Provincetown resident and a contributor to the Independent, had just gotten his master’s in history at UMass Boston and was living in Philadelphia when he happened on a trove of archival material at the LGBT Center of Central Pennsylvania History Project. There, Barry Loveland had amassed a collection of 50 gripping oral histories of local gay, lesbian, bi, and transgender people, and in reading them, Burton, who had spent most of his adult life as an out gay man in Houston and Boston, realized, “I’d been living in a bubble.”

Central Pennsylvania, which includes most of the state between the metropolitan areas of Philadelphia in the east and Pittsburgh in the west, is deeply conservative, religious, and socially regressive. The LGBTQ people who live there were largely closeted and isolated from one another in the pre-Stonewall era, and as gay liberation exploded in urban areas after the late ’60s, they had few visible paths to lift themselves up.

“I never had to deal with what people had to deal with in non-urban areas,” Burton says. “I realized I had been blessed my whole life. I was thankful for what had been achieved in gay liberation, but I wasn’t involved in activism. I wanted to give back to the community.”

He also realized that what has been written about non-urban gay life has rarely dealt with the formation of an LGBTQ community. So, with the help of Loveland (duly credited with co-authorship), Burton re-reported the oral histories, researched the evolution of LGBTQ groups in central Pennsylvania, and structured his history chronologically.

The result is a satisfying mix of the personal and the political that offers a view of the queer communities of the region with surprising depth and breadth.

Burton begins with the evolution of the gay and lesbian bar scene, from the ’50s through the ’70s, in the small cities of Harrisburg, Lancaster, and York. In the absence of any sort of social nexus, bars were the only places where homosexuals of that era could actually meet each other and be themselves. Though patrons were often harassed and arrested, they had no recourse — the consequences of being exposed were catastrophic and not infrequently led to suicide.

The effects of gay liberation began to trickle in during the late ’60s, but uniting gay people with a sense of community and purpose was exceedingly difficult in central Pennsylvania. One man, Jerry Brennan, formed Dignity/Central Pa., a branch of the Catholic gay organization, which served as a way for people — many of them Protestant or Jewish — to socialize without a bar scene. A gay switchboard was formed, a kind of queer 911, and also various newsletters. Burton diligently traces these early efforts at creating support systems.

Pride celebrations were started (and halted and restarted), many years after the annual march had become a regular ritual in New York and in other big cities. One lesbian, Nancy Helm, established a gay bookstore in Lancaster, only to see it firebombed twice; the threats to her well-being were so continuous, she gave up the business within a year.

Eye-opening early anti-discrimination efforts by Gov. Milton J. Shapp, working with activists in the ’70s, are detailed. The rise of student organizations at Penn State — also located in the region — are likewise revelatory. So, too, is the landmark case of Jennifer Harris, a black lesbian student basketball player at the university who made a legal case against abusive and discriminatory treatment by a bigoted coach, Maureen “Rene” Portland.

Burton documents the region’s desperate response to the AIDS epidemic in the ’80s and ’90s, and, later, the journey of transgender activist Mara Keisling.

One of the oral histories in the book is that of Lorraine Kujawa, who started a popular lesbian newsletter, The Lavender Letter, and retired to Provincetown, where Burton interviewed her. “She was a teacher in the school system in Harrisburg,” Burton says. “All those years she taught, she never came out. No one knew she was gay. And now she’s happy to be living in Provincetown and to hold her partner’s hand in public.

“The people who fought for their rights in places like Lancaster — they were very brave,” Burton continues. “They’re not national figures, but they’re part of a gay history that needs to be told. I’m so proud to be able to document that.”

Keystone Quest

The event: Virtual reading from Out in Central Pennsylvania and talk by author William Burton

The time: Saturday, June 27, at 5 p.m.

The place: eastendbooksptown.com, via Zoom; prior registration is required

The cost: Free