In the course of an artist’s lifetime, a recurrent theme may emerge almost of its own accord, with an urgency that cannot be ignored. That has certainly been the case for Daniel Ranalli, whose photographic works over the past few decades have repeatedly, and with increased focus, drawn attention to the effects of climate change on our planet and the Outer Cape in particular.

Ranalli is one of the artists taking part in Broto, the annual art-science-climate conference that was originally scheduled to happen live in Provincetown on May 16-17, with paid admission to its panels and workshops. Because of the current stay-at-home directives, director Ian Edwards took Broto online, and it will unfold virtually on the same dates, with free access worldwide (register at broto.eco). Ranalli is part of a panel on Saturday, May 16, at 2:30 p.m. titled “Time as a Muse,” along with artist Elena Soterakis, sculptor Jonathan Latiano, and Julia Buntaine Hoel, founder of SciArt Initiative.

Climate change, says Ranalli, has been a “thread in my work going back a long way.” His many photographic series, such as Snail Drawings, Zen Dunes, and Whale Strandings, arise from his deep interest in the natural world and the passing of time.

In 1995, Ranalli created an image of the Provincetown Monument with its base underwater, a startling vision of rising sea levels. It has since become a familiar local icon.

“I originally did the piece for an auction at the Fine Arts Work Center,” he says. “I titled it Provincetown Monument: High Tide July 2024, a date which, at that time, felt like the very distant future. That date stuck with me, so about 10 years later, I did the first in my Remapping Series of Cape Cod, where I show what the Cape would look like if the sea level rose 10 feet.”

Ranalli has since created similar maps for this year’s Broto conference. “Ian wanted to look 400 years ahead to 2420, as a reflection of the 400 years since 1620, when the Pilgrims first encountered Cape Cod,” Ranalli says. “I decided to do a 20-foot rise in sea level, which turns the Outer Cape into an archipelago, with just the scattering of a hundred islands.”

Originally from coastal Connecticut, Ranalli grew up in a blue-collar household and came to art after dropping out of a Ph.D. program in economics. With a career spanning more than 40 years, Ranalli has work in dozens of museum collections, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

He discovered Cape Cod in the 1980s, when he was hired as the second executive director of the Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill. “I summered in Truro for three years and was completely smitten by the Cape and its beauty,” Ranalli says. He helped to set up the precursor to the Wellfleet Harbor Actors Theater while living in a dune shack above Newcomb Hollow — a shack that has since collapsed into the sea — and bought his Wellfleet home by the bay in 1986.

He became an associate professor of art history at Boston University in 1988 and founded the graduate program in arts administration there in 1993, all the while spending as much time as he could on the Cape. “My work changed once I got here,” he says. “I had been doing very abstract work and started doing pieces that came about by walking the beaches and building constructions out of seaweed and stones, knowing that they were going to wash away in the incoming tide.”

In 2011, Ranalli began his ongoing Daily Observances project, for which he walks from his home every morning at 7 a.m. to the bayside bend on Kendrick Avenue to take a photograph. “Everybody in Wellfleet has driven by that corner,” Ranalli says. “It always causes your glance to move toward it. I’m lucky that I live less than a 10-minute walk away. Every morning, I notice how different the sky is, how the waterline changes. In a way, it is the simplest possible construction of an image, composition-wise. In some frames, the water is as smooth as a mirror.”

The series builds on the idea of paying close attention, Ranalli says: “That is one of the things artists do, photographers do — pay attention.”

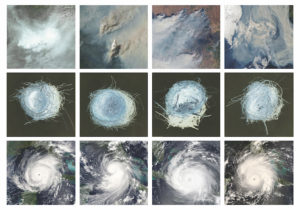

Since his retirement in 2015, Ranalli, who is represented by the Schoolhouse Gallery in Provincetown and Gallery Kayafas in Boston, spends more than half the year in Wellfleet with his wife, artist Tabitha Vevers. Recently, he has been working on a series titled Fire and Ice, which matches NASA satellite photographs of wildfires, floods, hurricanes, and glacial calving with his own photographs, taken on Cape Cod.

“I’ve always thought that NASA satellite pictures were incredibly beautiful, and I always wanted to do something with them by integrating them with my own work,” Ranalli says. One montage in the series juxtaposes Ranalli’s images of birds’ nests with satellite imagery of hurricanes and fires. “I was thinking of birds, descendants of dinosaurs, which have gone extinct, and that it is reasonable to assume that humans will probably go extinct as well,” he adds.

Despite his contemplating the demise of our species, Ranalli has not given up hope. Like other observers, he sees a silver lining for our planet in the current pandemic.

“There are satellite photographs showing much less air pollution,” Ranalli says. “Maybe people working from home will become the norm, saving on commuting. I believe we do have a chance to rearrange the way we live on this planet, and there are an awful lot of people who want to do that.”