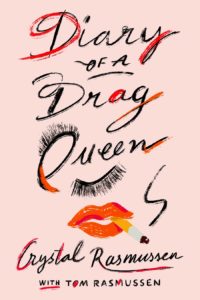

Drag queens are a familiar part of street life in Provincetown, and thanks to stars such as RuPaul and his Drag Race reality show, they’ve become a familiar part of the media landscape. Audiences straight and queer have flocked to drag performances in town — they’re even a hit for bachelorette parties. British writer Tom Rasmussen, who as a drag performer goes by the name Crystal, has been the beneficiary of that familiarity. But how much do we know about the inner lives of drag queens? Rasmussen attempts to satisfy our curiosity with an equally outrageous and perceptive account of one year in such a life, titled Diary of a Drag Queen. Though Crystal is often referred to in the press and by the public as she/her, Rasmussen’s gender identity is nonbinary, using they/them, which highlights the fact that two personalities are telling this story, since both Crystal and Tom are listed as authors of the book.

In it, Rasmussen takes us through that defining year with brutal honesty. Born in Lancaster in northern England to a working-class family, Rasmussen went to Cambridge to study veterinary medicine. While at Cambridge, they were always keenly aware of a sense of otherness — not only in terms of sexuality, but also in the social, class, and economic differences that had to be recognized and overcome. “I came from the bottom of the mountain, a place where I had never even known about class because the top was not in view,” Rasmussen writes.

The book opens in New York City, with Rasmussen working in the publishing industry as a personal assistant for a fashion magazine editor. Realizing that they were never going to make it in the world of fashion, Rasmussen heads back to the U.K. to pursue a career in London and to be near family, friends, and, especially, Ace, their best friend and true love.

In London, problems persist. As a drag performer, Rasmussen is not able to find steady work. Ace is dating another man, so the hoped-for romance flounders. Rasmussen gets an internship at the fashion magazine Chic but is soon fired for telling the editors that the publication is too racist. And finances are tight — they are continually overdrawn at the bank.

As the year progresses, things begin to turn around. Rasmussen joins a drag troupe called Denim, which starts performing in high-profile queer venues in London and all over the U.K. Rasmussen’s talents as a journalist find an outlet in periodicals. And Ace eventually comes to realize that Rasmussen is the love of his life.

The path to a more satisfying existence is hardly seamless, however. As we take the journey with Rasmussen, we are treated to vivid and hilarious stories of adventures good and bad, not to mention the graphic details of many erotic encounters, the cumulative effect of which can be a little much. Rasmussen does not shy away from sharing their exploits, as well as the harassment and suffering they endure, the moments of low self-esteem, or the vicious physical attacks.

“Drag is about both sisterhood and stardom, and those two things require respect: for each other and for yourself,” Rasmussen writes. “As queer people, we are taught to disrespect ourselves because we’re constantly disrespected, and so becoming a drag performer is so much about unlearning that.”

In one horrific incident of physical abuse recounted in the book, Rasmussen, who had just left a drag performance, describes a man screaming vile homophobic slurs, smashing a bottle, and chasing after them. Unbeknownst to the man, a bus is careening down the street towards him. Rasmussen instinctively stops and pushes the attacker out of the bus’s path, averting a likely lethal accident. After the bus passes, the two look at each other, and the man earnestly thanks Rasmussen. Then, looking Rasmussen squarely in the eye, he reaches up and strikes the drag queen so hard in the face that “I heard my nose crack and my brain bounce around my skull,” Rasmussen writes. “My sight disappeared; my mouth filled by blood coursing from some unknown location on my face.”

Of this surreal attack, Rasmussen says, “Imagine a scenario in which someone despises your existence so vehemently, so fervently, that, even when you have genuinely saved their life, they feel you still deserve physical punishment for being.” Rasmussen’s level-headed observations of moments like this are what give the book depth.

And the book is filled with insightful reflections on drag culture. “People think drag queens are stupid,” Rasmussen writes. “This is misogyny in action: they think that because we feminize ourselves, because we spend a lot of time on makeup and hair and getting exactly the right look, we are vapid, bitchy, and stupid. We created a culture that the world marvels at. We know how to make a mockery not of women, but of what you (men) think women should be, whereas you (men) just, simply, mock women. It’s stupid to think drag queens are stupid.”

Diary of a Drag Queen is anything but stupid. Rasmussen tells the daily stories of his year-long journey with intelligence and wit. The amount of explicit sex recounted might be off-putting to some, but what Rasmussen has written, as Crystal and Tom, is raw and powerful, entertaining and thought-provoking.