“In the labyrinth,” writes Oliver de la Paz, “there is constantly the problem of proximity: how what is understood about where you stand depends on where you stand.”

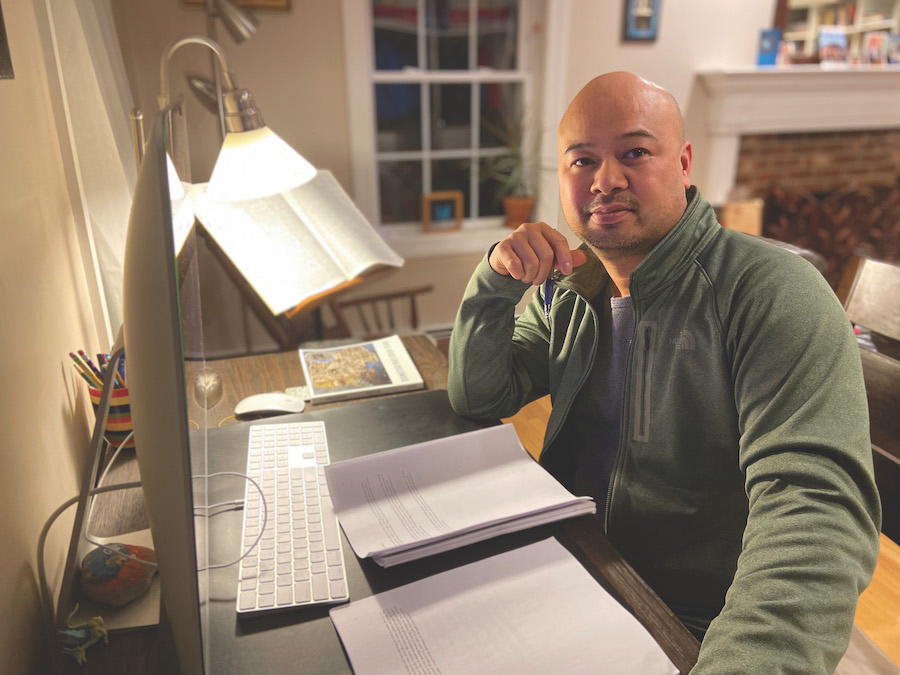

A poet for whom multiple possibility and “neurodiverse” perception of the “surface world” are core subjects, de la Paz is the author of five books, most recently The Boy in the Labyrinth, and the co-editor of an anthology of contemporary persona poems (To Face the Faces). Currently a visiting writer at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, he will give a public reading there on Friday. Though he is new to the Cape, through the experiences of writers he has known — and because of Mary Oliver’s ties to the place — he says he has always imagined Provincetown as being “rich in poetic energy.”

Born in Manila in 1972 — the same year that Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law in the Philippines, abolishing freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and other civil liberties — de la Paz first came to the United States as a child, after his uncle, a student protester, had been identified as “an insurgent,” he says, and “placed on Marcos’s blacklist.” His parents left “as part of the brain drain.” His mother, who had practiced medicine, wasn’t able to do so when she first arrived in the U.S., and she eventually found work in the small town of Ontario, in eastern Oregon, where de la Paz grew up. His third book, Requiem for the Orchard (2010), is, he says, “very much a magical realist reenactment of my early life in the U.S. after immigration.” It’s an attempt “to reconcile that place with who I am today.”

Ontario is a place for which “I hold a lot of ambivalence,” he says. “It was hard on my family to live there, where there were so few Asian families. We were the only Filipino family for quite some time. There were a number of adjacent military bases, and my mother tended the children of some soldiers who had recently returned from the Vietnam War. So there was always some kind of tension with my family and the community my mother served.”

Does de la Paz feel any kinship with the work of Madeline DeFrees, who was born in Ontario in 1919? “She was an incredible poet,” he says. “I would eventually meet her, and she and I shared some old community gossip.” Her experience, however, “was certainly different from mine.”

A principled connection to others seems to guide de la Paz’s poetry. “Inhabiting a character is,” he says, “a poetic mode, that, by its very nature, asks the writer to exercise a tremendous amount of empathy towards the character being rendered. You’re imagining that you are the person you are writing about, and so you must also understand what motivates that character.”

Clues to his process appear in “Self-Portrait With Taxidermy,” in which he writes: “one by one, we are called/ to make something ready. To give back form/ and put everything back in its place.” In that poem, de la Paz says, his speaker “was trying to piece together a bird that had been shot up with birdshot.” As a result, “something that had been irrevocably changed, like the body of a bird or even one’s experience of the past,” is “remounted and put on a display as an exact replica of that thing,” he says. It’s “certainly suggestive of the struggle in making art.”

In The Boy in the Labyrinth, de la Paz creates a hybrid classical-contemporary form pieced together from Greek drama, Platonic dialogues, the Minotaur’s labyrinth, and an autism spectrum questionnaire, in which he plays with standardized ideas about sound, color, taste, and perspective.

“Scale is not a concept. It is a veil,” he says. In “A Story Problem,” the reader is presented with dispiriting choices that seem to question, even reject, the confining notion of color: “The flowers are A. Red. B. Fuchsia. C. Yellow. D. White. E. None of the above.”

Possibility and curiosity drive the questions and responses: “Because the color of the red door renders it mute./ Because the color of the die-cast car is an empty blue/ and the sound of our voices could be any possible starling/ we are not here. He is not here. And what of the place you reside/ if you don’t reside in it? When then does your body blink?”

In Labyrinth, there’s a tentativeness to the speaker’s perceptions, perhaps because they’re not the speaker’s own. “I was very nervous in treading into territory that I had no right to enter — namely, writing about the perspectives of my neurodiverse children as a neurotypical parent,” he says. “Even though I thought it important to strive for a level of accuracy in the rendering of my children’s perspectives, I also knew that it was impossible/bewildering to imagine that such a move was possible or even appropriate.”

To perceive any place in de la Paz’s inventive and allegorical poems may mean to move through bewilderment into amazement. “The making of stories, poems, and art for me is to present the questions that fill my mind in a manner that others may see and perceive my wonder,” he says. “From there, I imagine the possibilities such work could generate should lead us to dialogue.”

Into the Labyrinth

The event: Reading by poet Oliver de la Paz

The time: Friday, Jan. 17, at 6 p.m.

The place: Fine Arts Work Center, 24 Pearl St., Provincetown

The cost: Free