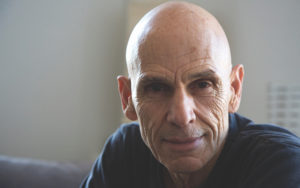

Eighty-one-year-old Joel Meyerowitz, éminence grise among Provincetown photographers, was in Manhattan in late October. The occasion was a narrated slide show and book signing hosted by Aperture, his publisher, at its Chelsea gallery, which was packed. Out since Sept. 24, Meyerowitz’s new 160-page monograph, sized for a coffee table, is titled, simply, Provincetown.

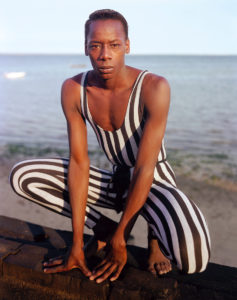

After talking about his pioneering 1960s New York street photography, Meyerowitz moved on to Provincetown, in which summer’s sky and sea serve as idealized settings for all manner of dress, undress, and sun-frosted skin. The book is a time capsule of portraits of the town’s colorful denizens in the late ’70s and early ’80s as they respond to the novelty of a six-foot-plus photographer standing behind a Deardorff 8-by-10 view camera on a tripod. Given the time period, and those lost to AIDS, certain portraits hold a special resonance. The cover image, “Darrell,” is of a black man in a tight brown-and-white-striped one-piece garment. Meyerowitz describes him as a dancer.

By the mid-’70s Meyerowitz’s work was evolving. “I decided to switch to a large format camera, the antithesis of a street camera,” he says, speaking by Skype from his home in Tuscany. His close friend Murray Reich suggested that he go to Provincetown. Reich, Meyerowitz says, described the locale as “just like 8th Street in Greenwich Village — full of interesting people, Portuguese fishermen, an artists’ colony, lots of playwrights, musicians, poets.” Meyerowitz, a long-distance swimmer, came to town during the winter of 1976 with his son, Sasha, and Reich. “I immediately went to a real estate agent, signed for an East End summer rental. The first pictures I made with the 8-by-10 camera were made on Cape Cod,” Meyerowitz says excitedly in his high-pitched, raspy voice.

Eventually, he would buy a beachfront cottage (sold in 2016) and befriend Christopher Busa and Ray Elman, co-founders of what became the Provincetown Arts Press. From the mid-’80s through 1993, Meyerowitz regularly did cover portraits for Provincetown Arts without charge (Stanley Kunitz, Robert Motherwell, Norman Mailer, Annie Dillard) as a “gesture of support for the arts community,” Elman says, speaking by phone from Miami.

Provincetown is a record of the photographer’s 35-year love affair with the town, beginning when such landmarks as Dairy Land, with its extravagant neon, ruled Shank Painter Road. Meyerowitz captured this quintessential example of Americana as his hero, Robert Frank, might have, but in bright color. Several images in the book are taken from other Meyerowitz volumes; most are previously unpublished. And if, as Meyerowitz asserts, individuals posed themselves, the lighting and composition are reminders of his brilliant use of color, pattern, and design.

In pursuit of subjects, Meyerowitz posted an ad in the Provincetown Advocate: “Remarkable People! If you feel you were remarkable because of a birthmark, scar, personal experience, etc., or know someone remarkable, I’d like to make your portrait.” Most subjects, however, were discovered on the street. Julia Goodman, speaking by phone from Boston, recalls working in a juice bar near the Governor Bradford when Meyerowitz approached, saying, “ ‘I’m working on a series of photos of redheads. Would you be willing to pose for me?’ ” Goodman was 16. “I was a shy person, really nervous,” she says. “I think he must have been aiming to capture the gawkiness, since that’s all I see when I look at the photo [in Redheads], with a giant scrape on my knee.”

During that same shoot, Meyerowitz had a Leica on hand for a Fuji promotional campaign. Goodman agreed that he could take some extra shots with the smaller camera, and later was paid $400 for it. She was thrilled. Her image would be displayed in Times Square and Madison Square Garden.

In Provincetown, Meyerowitz was shooting portraits as well as the seascapes and interiors for what would become his best-selling book Cape Light, originally published in 1979. It has since gone through multiple printings and has sold 150,000 copies, spawning posters and calendars. Other images would go into A Summer’s Day (1985), Redheads (1991), and now Provincetown. Why did it take so long to publish Redheads? The market for photography books was soft in the ’80s, Meyerowitz says. He eventually convinced Rizzoli it was time to publish Redheads — fortuitously, the publisher’s director was a redhead. “Rizzoli succumbed to the temptation,” he says, “and the book was very successful.”

Sarah MacDonnell is an actress and longtime East End resident whose beachfront family home is a short stroll from the property Meyerowitz owned. He photographed her in 1980, when she was in her teens. Images from that shoot appeared in A Summer’s Day, on the cover of Redheads, and now Provincetown. “These are beautiful portraits of a young woman,” MacDonnell says by phone from New York. But, she adds, she was never told when or where her image would be used. “Even if he didn’t know at the time the photo was taken,” she says, “you can call somebody, tell them their image will be on the cover of a book, and give them a copy. Or give them a copy of the photograph,” MacDonnell says. Still, at the Aperture opening, she and Meyerowitz reconnected with pleasure. They are part of each other’s life history.

On notifying subjects, Meyerowitz says, “When I made the photographs back in the day, every single person that I spoke to, I took their name and address and told them it was likely I would be publishing these pictures or showing them. And if someone would say to me, I don’t want the image to be published, I would not take their photograph.”

Meyerowitz often speaks of finding “the figure of his truth” as a portrait photographer. “There can be a sense of anima, a spirit that is recognizable to me in a more profound way,” he says. “Those are moments of intimacy, in which otherness is communicated and shared…. I think photographers know how to harness this kind of elemental sensitivity, from person to person.”