WELLFLEET — Five hundred yards upstream of the Chequessett Neck bridge, sequestered on a maintenance access road, a $7-million dike designed to prevent flooding in the Mill Creek sub-basin is nearing completion. It marks a milestone in the restoration of the Herring River salt marsh and tidal estuary.

The primary structure on Mill Creek, consisting of five tidal gates and a steel-sheet retaining wall, is “done and operational,” said Geoff Sanders, the natural resource management division chief at the Cape Cod National Seashore, at a June 12 meeting of the Herring River Executive Council, which brings together the town and the Park in directing the Herring River Restoration Project.

That means “Mill Creek is flowing through the water control structure now,” Sanders told the Independent on June 16. Contractors are still working on a catwalk for maintenance personnel to access the structure, he added. This part of the project should wrap by September at the latest.

The structure is one of two recent steps forward in the $70-million restoration, which is funded primarily through state and federal grants.

In March, contractors completed the southern bay of the permanent bridge replacing the Chequessett Neck Road dike, according to project representative Wes Stinson of Apex Environmental Partners. It was that dike, built in 1909, that has choked the river’s tides and natural estuary habitat since.

Mill Creek’s Place in the Flow

The Mill Creek structure has been a recommended component of the restoration project for 35 years, as John Portnoy, Alice Iacuessa, and Barbara Brennessel wrote in Tidal Waters, their 2016 history of Wellfleet’s Herring River.

After the dike’s construction, summer residences and development in the Mill Creek sub-basin sprouted as the tideline moved lower. The Chequessett Golf Club was established in 1929; today, five of the course’s nine fairways, now owned by the Chequessett Yacht & Country Club, lie in the river’s natural floodplain.

In 1990, a study by hydrologist William Nuttle found that without a dike to control the creek’s flow, its restored tidal heights would flood those low-lying fairways with salt water.

The near-complete structure, spanning 158 meters, is designed to protect those low-lying properties once the tidal range is restored, Seashore Deputy Supt. Leslie Reynolds told the Independent in an email. (The Chequessett Club received $6.7 million in 2021 to raise and renovate its five lower fairways by 6.36 feet, the maximum high-tide level if the new structure’s gates were fully open.)

Each of the new structure’s 1.5-meter culverts is a combination sluice and flap gate, Reynolds wrote, allowing drainage but not inundation: ebbing waters at low tide can travel unhindered through the flaps, but high tides are barred from rising past the sluiceways.

In the future, Reynolds said, “the gates can be raised to allow tidal flow inland of the structure and more salt marsh restoration,” but only once additional flood mitigation on properties like the golf course is completed.

Raising the gates would be critical for ecological restoration, said Portnoy, a retired Seashore ecologist. When the dike choked the flow of salt water to the river’s tidal estuary, he said, former marshes in tributaries like the creek were overtaken by thickets of black cherry, shrubs, and invasive Phragmites, which decreased flow and increased water retention. Releasing brackish tides upstream would kill those thickets and create conditions for marsh flora to thrive, Portnoy said. And in that case, fresh water carried downstream by Mill Creek would encounter not a morass of invasive plants but glide through the structure’s five culverts toward the Chequessett Neck bridge.

The Mill Creek structure is the project’s sole infrastructure element that is owned outright by the National Park Service, Sanders said.

Construction on the water control structure began in spring 2024, according to Reynolds, with the $7 million provided by the Natural Resource Conservation Service, an agency of the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture. The National Park Foundation provided an additional $1 million for engineering and contract support.

“We’re all looking forward to restoring tides — not only higher high tides, but lower low tides,” Portnoy said. A broader tidal range “drives production in these marshes and provides access for marine animals.”

New Bridge and Gates

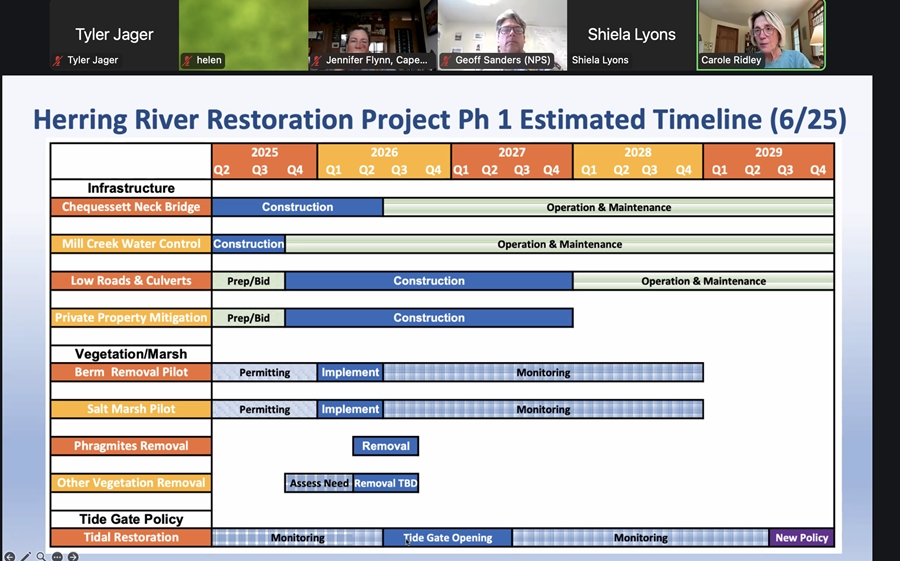

At the June 12 meeting, Stinson and Sanders presented the council with an updated restoration project timeline. Though they said that the timeline was subject to change, Stinson estimated that the permanent Chequessett Neck bridge would be completed by mid-2026.

In March, Stinson said, crew members with contractor MIG had successfully redirected the river’s tidal flow from the dike’s existing three-bay culvert toward three open gates on the permanent bridge’s southern bay.

The transition has not yet affected the rate of flow under the bridge, Stinson told the Independent. That’s because the southern bay’s two flap gates and single sluice gate are designed to maintain the flow conditions of the original three-bay culvert constructed in 1974. Even so, for those involved, this step is exciting. “It’s really the first time since the 70s that the path of the river has been shifted,” Stinson said.

Contractors are now starting on the middle and northern portions of the permanent bridge — the last part of the bridge-building phase of the project.

Last year, engineers were waiting for Verizon and Eversource to connect electrical wires across the temporary bridge before starting work on the old dike. That step has since been completed, Stinson said, and crews are now working within sheeted coffer cells to demolish the old culvert entirely.

A Tale of Two Grasses

So far, little vegetation has been cleared from the Mill Creek sub-basin, said Reynolds. Phragmites was cleared only as needed to build the structure and clear the immediate surroundings. Future clearing work will be needed in the lower part of the river, she wrote.

“If and when” the structure’s gates are opened for upstream saltmarsh restoration, Sanders said at the June 12 meeting, the Phragmites would be cleared and displaced with native Spartina cordgrasses.

Some members of the council suggested caution when removing the Phragmites. Though the reeds are known to choke waterways, Helen Miranda Wilson said, their long roots could hold soil and absorb chemicals from ground and surface water.

Phragmites do remove contaminants and service the ecosystem, Sanders said — but only “in the absence of anything else.” He added, “I think we would see that Spartina will perform the same types of services that Phragmites does and probably provide even more benefits.”

Portnoy told the Independent that while it’s true the invasive reeds absorb high concentrations of nitrogen and carbon in runoff, that doesn’t necessarily outweigh their negative effects, which include mosquito breeding and decreased species diversity. He pointed to a 2022 finding from the USGS’s Woods Hole Coastal Center that Phragmites-impounded wetlands in the Herring River contribute to increased methane emissions.

Once salt water reaches the sub-basin, Portnoy said, black cherry and other species would die almost immediately. But “Phragmites is tough,” he added, because the reed can tolerate up to about two-thirds the salinity of regular seawater.

“Like all ecological questions, it’s a complicated calculus,” said Seashore Supt. Jennifer Flynn. She added that Phragmites removal could affect upstream flow over the golf course’s fairways, a worry that she said club representatives had expressed.

Sanders said that the NPS would continue monitoring changes to sediment flow as more extensive Phragmites removal occurred in mid-2026, according to the updated timeline.

In the next stage of the project, project coordinator Carole Ridley said, Wellfleet is preparing a bid for contractors to elevate low-lying roads and replace culverts along those roads. The town is working with Friends of Herring River to advertise the bid this summer, and construction on that stage is slated for the end of 2025.

Stinson and Sanders were to present their updates on the restoration to the select board on June 25 at a 2 p.m public meeting at the Adult Community Center.