Many visitors to Provincetown have admired the funky, colorful Bob Gasoi Memorial Alley beside Shop Therapy at 290 Commercial St. Few, however, are familiar with Arnold Charnick, the artist who took on the daunting challenge of refurbishing what was left of Gasoi’s original mural in 2016 after Shop Therapy owner Ronny Hazel moved the landmark “alternative lifestyle emporium” from the East End to the center of town. With a jigsaw, Charnick cut out each salvageable figure in the former mural, which used to bedeck the old Shop Therapy. He then restored and reassembled them in a new constellation, including new work he added, to create the Memorial Alley, which many consider even more magical than Gasoi’s original.

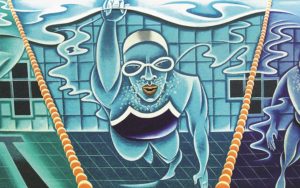

At 73, Charnick has created an impressive body of work in his “deco style” — his murals can be found in New York City, Provincetown, and other locations here and abroad. Now he’s finished something new. When Charnick moved back to Provincetown this year (he’d lived here in the ’70s), Hazel asked him to create a second mural on the opposite side of Shop Therapy from the Memorial Alley, facing west. This time the piece would be entirely his.

“Ronny suggested, since the alley is very popular, that I paint something on the other side of his building to make it complete,” Charnick says. “Of course, I agreed.” Thinking out loud, he suggested it be a garden, to which Hazel blurted out, “An ‘Octopus’s Garden in the shade!’ ” Charnick ran with this line from the Ringo Starr tune and came up with Octopiece, a mural now visible from Ryder Street and Provincetown Town Hall. Instead of literally depicting octopuses, Charnick played with the number eight: eight orchids, eight butterflies, eight sunflowers, eight petals, with three psychedelic mushrooms in the center from which the whole piece flows out. “It’s my version of a garden,” he says.

He likes to layer his work with innuendo. The orchids in Octopiece, for example, are “very erotic, comical, and alien,” with images hidden in the blossoms, he says. “You see more as you look: eyes, a bearded man, even a phallus.”

Much as he did with Gasoi’s mural, Charnick cut out individual pieces with a jigsaw and assembled them, directing his “fearless, ladder-climbing assistant,” Bo Johnson, a local house painter, from 60 feet away. “Most mural artists create a model, then copy it onto a wall,” he says. “I can’t work that way, because it’s not fun. I’d rather do things intuitively.”

To make the piece more sculptural, Charnick looped in a green garden hose to create a border between sky and garden, and wired antennae to the butterflies. “Everything was bought locally,” he adds. “I have a quote by which I run my life: ‘The means is always at hand.’ And it’s true —what you need is usually right there. Just look around.”

As a young boy growing up poor in the Bronx, Charnick turned to art “because it was the only way for me to escape and express myself,” he says. “I didn’t have any toys. We didn’t have a TV. We didn’t have a car. We had nothing.” When he was 12, Charnick’s mother let him paint a mural in the family’s living room. “It was just a shitty little apartment,” he says. “But she knew I was talented. After that, murals became my thing.”

Charnick’s artistic ability got him into New York City’s High School of Music & Art, which “pretty much changed my life,” he says. “I knew that I wanted to become an artist, because that was all I could do. But that experience set me on the path.”

Charnick was then accepted to Cooper Union’s School of Art but he dropped out after a year and a half to follow a group of friends to Provincetown. “I was 18,” he says, “and it was fantastic.” He shuttled between Provincetown and New York, returning home for “a hot meal and a place to sleep.” He finally moved here full-time in 1968, remaining until 1980, when he returned to New York, though he still came for summers.

“Now the circle has led me back, and I’m here to stay,” Charnick says. “This is a great place to be. Demographically, it has changed — there is more money, and everything is more expensive. But it’s still a playground, and, for me, that works perfectly.”

Many of Charnick’s early murals were created here. “I’d see a wall and think a mural belongs there,” he says. “I’d go to the owner, tell them I was good, and offer a deal they couldn’t refuse. One mural would lead to another.”

Few of those pieces still exist. His very first Provincetown mural was the backdrop to a nightclub in the Provincetown Inn. Another, on the Crown & Anchor, was destroyed in the Whaler’s Wharf fire of 1998.

“All of my projects have some crazy story,” Charnick says with a boyish grin. “That’s why I get a kick out of what I do. Don’t get me started, or we’ll be here all night.” And while some of his murals have “sparked controversy over the years,” Charnick says his clients “always tend to be very happy.”