Pride, being one of the seven deadly sins, has good and bad sides to it. It’s like patriotism. To the extent that it means self-love and self-respect, it’s essential and a positive force. But to the extent that it’s exclusionary, about yourself and no one else, it can be hurtful and worse.

For gay people of my generation, pride was a key to happiness and self-fulfillment. It was the basis for coming out: letting the world know that you are gay and not hiding it. Not everyone who was gay or lesbian was capable of “passing” — putting a straight face on being in the closet. But many were, and did. In the same way that Jews might present themselves as gentile and “high-yaller” blacks might present themselves as white — pride makes the very idea offensive. Why should you prefer to be anything that you’re not? It makes you complicit with bigotry. If you use the false pretense to survive, it’s sad. If you use it to achieve success, the end result gets murky.

Hatred of LGBT people has always been belittling: you were seen as diseased, perverted, disgusting, weak, laughable, pathetic, worthless. Coming out took pride, and the annual gay pride marches and celebrations were always out and public.

The Stonewall Riots, which began on June 28, 1969, when the police raided the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street in New York City, became a symbol of gay pride. It was a pivotal breaking point: led by fierce drag queens, gay people fought back, no longer sheepishly accepting their persecution. Pre-Stonewall, pride came in fitful bursts. Afterward, it was a rallying cry, a credo, the basis for a full life.

On June 28, 1970, a march commemorated Stonewall, starting with hundreds of people in Greenwich Village and accumulating thousands in the trek uptown to a rally in Central Park. It was symbolic: an emergence from the ghetto.

It became a tradition on the last Sunday of June and spread to other cities and nations. What started as a political march evolved into a celebratory parade.

I came to New York for graduate school in 1978. I was out but still finding my way to a life on my own in the city. My first pride march was a few years later. What I remember was being indoctrinated into the ritual by a friend in 1982. He pointed out to me and my boyfriend (now husband), Ed Christie, that a drag queen on the front lines of the march, Sylvia Rivera, was one of the Stonewall rioters. We marched up Fifth Avenue, past St. Patrick’s Cathedral, into Central Park. It was exhilarating to be among many thousands of gay people in the middle of the street, cheered by onlookers. But being out was no longer new to me, so the experience was not especially revelatory or affirmative. I was no longer coming from a place where being in the closet was the norm.

Heritage of Pride took over the march in 1984. It had become a parade, with floats and costumes, and less political. Controversially, the parade started uptown and went down Fifth Avenue to the Village. Some said it was because of the bars: they wanted the throngs to end up downtown. But the symbolism had changed.

Rivera’s presence at the march, along with her friend, Martha P. Johnson, both of them pioneers of transgender liberation, is worth noting. In the early ’70s, in order to put a macho face on gay pride, drag queens were often disinvited. They were considered embarrassments. It was disputed whether Rivera actually was at Stonewall, though Johnson certainly was. Any discounting of drag queens’ crucial role in the riots was a cowardly P.R. move. It reflected an underlying sexism, racism, and transphobia in the gay movement at the time: Rivera was Latina; Johnson, black. More to the point: it was the flip side of pride.

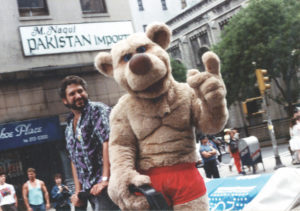

Ed and I went to the Gay Pride Parade most every year till the mid-’90s. Ed, who was a puppet designer and builder, would go as Brucie Bear, a walk-around character he created: a huge, musclebound gay bear in a tank top and gym shorts. (Ironically, this was before the Bear movement.) One year, we borrowed a car and drove in the parade with actor and playwright Harvey Fierstein, who is a friend. In 1991, sans Brucie, we rode on a float for a play Harvey was performing in, The Haunted Host. The last year that I remember well, 1994, was the 25th anniversary of Stonewall. The city was bursting with millions of LGBT people from all over the country and the world. I remember thinking, haughtily, how much the out-of-towners looked like out-of-towners. By the time we shifted our lives to the Outer Cape, in 2003, Gay Pride was more of a fond memory than an essential ritual.

In a year when Covid-19 gives crowds (especially Trumpers) a threatening tint, and most Gay Pride celebrations, including Provincetown’s, have been canceled, what was once rebellious now seems a bit nostalgic. AIDS has made the gay male community more appreciative of support from lesbians, and leveled the playing field a bit. With the Supreme Court making non-discrimination the law of the land, coming out seems less an act of courage. Black Lives Matter makes us more aware of racism within the queer community. The transgender movement has come into its own.

Pride is as necessary as ever. But it’s more therapeutic than revolutionary.