The writer Nick Flynn, whose work has been published in the New Yorker, Esquire, Paris Review, and a dozen books, came of age as a poet in Provincetown.

He was born in 1960 in Scituate, raised by his mother — his father adrift — and in the mid-1980s, after his mother’s suicide, Flynn moved to Boston and then to Provincetown, where he was a Fine Arts Work Center fellow during the 1990s and FAWC’s writing coordinator. He lived mostly on his houseboat, a 42-foot Chris-Craft, moored seasonally in the harbor. Friends came and went, and ties to this town of artists and renegades continue to ground Flynn’s work.

Especially now, Flynn’s followers will find his recent book, Stay: threads, conversations, collaborations, to be a source of solace, illumination, and a recognizable sense of place.

It’s a braided sequence of artist collaborations and previously published work that provides space for Flynn to plumb his archives and come up with a range of symbolic, aesthetic objects, including family photographs and ephemera.

“Collaborative work with other artists is such an important part of my work process,” Flynn says from his home in Brooklyn. The book includes a late-in-life letter from his difficult, troubling father, Jonathan Flynn, encouraging his son to be a writer. In Flynn’s memoir, Another Bullshit Night in Suck City, about the time he was a case worker at Boston’s Pine Street Inn, a homeless shelter, Flynn recounts being at the desk when his father is admitted. Photographs of his mother, Jody Draper, as a young girl, are particularly affecting — she remains a ghostly presence in Flynn’s life and work.

The poet Phil Levine, with whom Flynn studied at New York University, is another significant influence. Levine once returned a poem to Flynn, saying, “You have more light inside you than this.” Levine’s observation leads Flynn to note, in Stay, “I knew I had light inside me, and that somehow I would have to find a way to let some of it into my poems.”

Locally known collaborators whose presence is felt in Stay include Mark Adams, Mischa Richter, Amy Arbus, Nicholas Kahn and Richard Selesnick, Jack Pierson, and M. P. Landis. Their inclusions form a tapestry of Flynn’s friendships — art offers an avenue to keep them close.

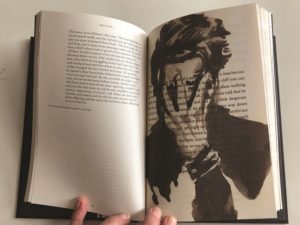

His work with Adams, a visual artist and cartographer with the Cape Cod National Seashore, began “when he appeared at one of my readings in the early 1990s,” Flynn says. “Mark is so open and curious. He knows so much.” Adams and Flynn recently did a workshop together at Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill, going out onto the dunes, where Adams would paint on pages in Flynn’s books with his signature walnut ink brushstrokes. Stay includes a portrait of Flynn by Adams painted on Flynn’s rendition of the myth of Proteus, the old man of the sea, who loses his way and becomes stranded on an island. In Adams’s portrait, Flynn looks down, his left hand sheltering his eyes. The words “Proteus,” “sea,” “rock,” dislodge,” and “thorns pierce” emerge from the text, suggestively.

From Proteus, Stay segues to a fragment from The Reenactments, Flynn’s memoir of his role as executive producer of the film Being Flynn, an adaptation of Another Bullshit Night. In the excerpt, Flynn finds himself discussing with Julianne Moore, who plays his mother, the pills she took; he also fields questions from director Paul Weitz about the gun his mother used to kill herself. “I get to the edge of knowing, then teeter back and forth,” Flynn writes. “It is all we can do, all I’ve ever done — stand before what I know, and pulse into the unknown.”

Another long-standing connection is with photographer Mischa Richter. “Mischa’s always working on something having to do with Provincetown — I save a lot of my energy for our collaborations,” Flynn says. “We always keep in touch.” Richter’s film about Provincetown, I Am a Town, premiered at the Museum of Modern Art in February. At Richter’s request, Flynn wrote a poem for the film, which became the source of its title. Flynn also wrote a poem for Saudade, Richter’s 2010 book of photographs; here, too, the theme is Provincetown, set against a background of change and loss.

Richter’s photograph Ray accompanies Flynn’s eulogy of beloved outsider artist Ray Nolin, who struggled with mental illness, first published in Provincetown Arts 2016. “Provincetown, when I got here, was a town of eccentrics, of outcasts, of misfits,” Flynn writes. “I was living on a boat then, and for a while, Ray stashed paints and canvases on board. I never knew when I’d find him set up, in the midst of painting.” Flynn describes how Nolin hid and even burned his artwork: “Ray was always working for God, not for you, and that was part of both his beauty and his difficulty.” Now that he’s gone, Flynn writes, addressing those who hid Nolin’s artwork to keep it secure, “If we really understand what Ray was trying to do, all his life, we will burn it.”

Flynn took photographs while living in Boston and includes some self-portraits in Stay. His early collages were assembled from torn pieces of the photographs. Wandering in new cities, he began making collages of ephemeral scraps he glued to cardboard — gum wrappers, grocery lists, drawings. The goal was to map interior as well as exterior space: to find out “where or who or what I am,” he writes.

“My writing is also very collaged,” Flynn says. “The whole book is a collage.” When he puts works next to each other, “the space between them means as much as what’s on the page.” Stay was released in hardcover, calling attention to the white ink embossed on black. The back cover, Flynn says, reads “a light coming on in an empty room.” That line, from his poem “Sudden,” investigates a newspaper reporter’s use of the word “suddenly” to describe his mother’s suicide.

In an excerpt from The Ticking Is the Bomb, which Esquire magazine described as a “painfully beautiful memoir of torture,” Flynn describes a theatrical scene when his daughter, Maeve, was a year and a half old, and he and his wife, actor Lili Taylor, were spending the summer in upstate New York. Flynn observed a light going on and off in Maeve’s room. Maeve, standing in her crib, he writes, was aware “that she was the one controlling” the switch. “Her room, from a distance, pulsed like a huge firefly.”