After World War II, when Europe was left in rubble and crushed in spirit, it lost its seat as the epicenter of Western culture. The art world largely shifted to the United States, a beacon of safety and stability that had remained relatively unscathed during the war. New York City drew artists from around the world and within the U.S. and blossomed as a mecca.

What they found, however, was not exactly a haven for creativity. The postwar era in the U.S. was a time of nuclear paranoia, anti-Communist witch hunts, and regressive morality. Artists, on the other hand, often strive to subvert the conventions and tenets of the society they live in. A struggle ensued. And when the Baby Boom generation reached its teenage years, beginning in 1958, the yearning for change gained momentum.

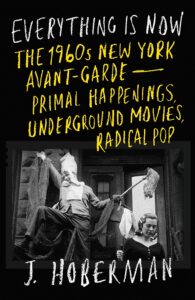

In his expansive and immersive new book, Everything Is Now: The 1960s New York Avant-Garde — Primal Happenings, Underground Movies, Radical Pop, J. Hoberman details how New York became a “cradle of artistic innovation. Boundaries were transgressed, new forms created. A collective drama was played out in coffeehouses and bars, at openings and readings, in lofts and storefront theaters and ultimately the streets. The dramatis personae were an assemblage of penniless filmmakers, marginal musicians, former painters and performing poets, as well as less classifiable and hyphenate artists, including political organizers. A significant few were émigrés from Europe and Asia, profoundly affected by their experience of World War II.”

Hoberman — a film and culture critic at the Village Voice for 40 years, the author of several books on the intersection of film and politics, and a longtime summer resident of Truro — has done an impressive job of documenting the heyday of the New York avant-garde from 1959 to 1971 in Everything Is Now.

“Born in 1949 and brought up in New York,” he writes in his introduction, “I lived through this period. Written in my seventies, Everything Is Now is an act of remembrance, underscored by a sense of belatedness. Although too young to have participated in most of these events I evoke, I am old enough to have experienced what might be termed the normalization of cultural craziness that characterized the 1960s.”

As a veteran journalist, Hoberman has prodigiously researched the salient art-world events of the decade, interviewing witnesses and participants and culling through years of reporting, much of it in “downtown” papers such as the Voice. For each chronological chapter of the book, he weaves a dense web of interactivity, linking each performance or reading or screening or happening to the work of other artists. The effect is indeed evocative: the swirl of events depicted in the book comes to life in a way that makes you an active observer. What was radical then may not seem so mind-bending now — although much of it retains its outrageousness — but Hoberman’s “act of remembrance” provides a thorough context in which to experience it the way people did in the ’60s.

That is his particular expertise as a critic: Hoberman’s books often explore the films of various eras (the Cold War, the Reagan ’80s) through the prism of the politics and culture of their time. In Everything Is Now, he provides an account of events or artworks — say, a screening of Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures — along with critiques by influencers such as Susan Sontag or mainstream critics such as Bosley Crowther of the New York Times, as well as an update on relevant news coverage, such as power broker Robert Moses’s plans to demolish the neighborhood, riots in Harlem, raids by police, and official censorship. The determination of the artists involved, as well as the repressive reaction of the powers that were, is palpable.

Certain figures and personalities emerge as central characters in the book: Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs among the Beats; Bob Dylan among the folkies (his onetime girlfriend, Wellfleet’s Suze Rotolo, is a dedicatee); the Fugs and the Velvet Underground among rockers; Ornette Coleman among jazz musicians; LeRoi Jones (renamed Amiri Baraka) among poets and Black activists; Claes Oldenberg, Jim Dine, and Yayoi Kusama among artists; the Living Theatre’s Julian Beck and Judith Malina and comedian Lenny Bruce among live performers; Jonas Mekas among cinema mavens; Jack Smith and Ken Jacobs among avant-garde filmmakers (and their summer in Provincetown in 1961); and, of course, Andy Warhol and the Factory as a nexus for all these groups.

It’s both a personal and collective journey, and Hoberman’s enthusiasm for the drama of it all is evident, giving his clear, readable prose some energy, which is especially welcome for a 400-page book that’s jam-packed with cultural history. But it’s history that is increasingly relevant today, at a time when freedoms are being threatened and squelched. For those who lived through the ’60s in New York and those who are curious about the struggle that it was, Everything Is Now is a richly resonant resource.

Digging Underground

The event: Reading from J. Hoberman’s Everything Is Now

The time: Thursday, Aug. 28, 6 p.m.

The place: Provincetown Public Library, 356 Commercial St.

The cost: Free