Happy Birthday, Mary Oliver

To celebrate what would have been the late poet Mary Oliver’s 90th birthday this fall, the Truro Meeting House (3 First Parish Lane) will hold a reading of her work at 7 p.m. on Saturday, July 19. Organizer Ken Field says that more than a dozen people have signed up to read two to four poems. Marcene Marcoux, whose new book A Unique Sense of Place includes an essay on Oliver, will read an introduction.

Field says he discovered Oliver “a long time ago” when someone sent him her poem “The Summer Day,” which begins with one unanswerable question (“Who made the world?”) and ends with another: “Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

“Her work is so down to earth but also deep,” says Field. As part of the program, he’s asked readers to talk about their connection to the poems they’ve chosen or to Oliver’s work in general. “It’s important to personalize the readings,” he says.

Participants will read poems that span seasons — from “The Summer Day” to “Starlings in Winter” — and range in length from a few lines to meandering musings. Field says he’s “thrilled” at the breadth of the selections.

During some readings, Field and Rod McCaulley will play background music on alto saxophone, flute, and upright bass. But Field says the music won’t interfere with the sound of Oliver’s words: “Sometimes it’s helpful to sort of reflect, or to give a little acoustic vibe to the reading.” And some of the poems will be read without accompaniment. “Some people will prefer to read in silence,” says Field. In those cases, the music of Oliver’s language will speak for itself.

The event is free. See truromeetinghousefriends.com. —Dorothea Samaha

People and Places in Color

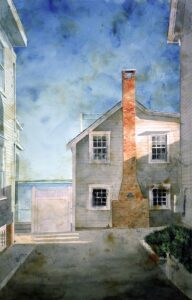

It starts with an early-morning walk with a camera and a sketchbook. Something catches his eye, like the way sunlight slants across a building — and Tim Saternow has just found the subject of his next painting.

This week, an exhibition of Saternow’s paintings of buildings in New York City and Provincetown is on view at William Scott Gallery (439 Commercial St., Provincetown). The two worlds he paints — his home and his summer vacation spot — are “quite different in terms of atmosphere and flavor,” says Saternow. But a common theme unites them: “When you look at old buildings, whether in New York or Provincetown, it’s almost like you can see the story of the lives of the people that inhabit these spaces.”

Some of the settings in Saternow’s work are familiar. The current exhibition features paintings of Commercial Street, Days Cottages in Truro, the harbormaster’s office on MacMillan Pier. But the paintings are meant to be more impressionistic than representational. “I begin to create a mystery to what’s behind the paintings,” says Saternow.

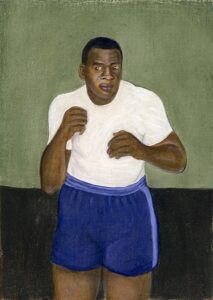

Also on view in the gallery is “Gym Boys and Couch Potatoes,” portraits by Daphne Confar. One painting features a Black man in a white T-shirt and blue shorts with his arms positioned as if he’s getting ready to throw some punches — except that his hands are half-open, and his unfocused gaze screams more “dove” than “lion.”

There will be an opening reception for the exhibitions at 7 p.m. on Friday, July 18, and the shows are on view through July 30. See williamscottgallery.com. —Lauren Hakimi

Two Modern Masters at PAAM

This month, the Provincetown Art Association and Museum (460 Commercial St.) is bringing together the work of Edward Hopper and Marsden Hartley, two significant American modernists.

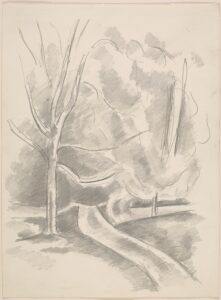

The drawings are grounded in each artist’s connection to place: Hopper’s Cape Cod and Hartley’s Maine. It’s a fitting exhibition for summer, both in the lightness of the medium and the subject matter. Many of the drawings look and feel like they were done on the beach.

Hartley finds his muse in Maine’s rocky beaches and its mountains, specifically Mount Katahdin, a repeated motif in his paintings that is represented here by one of the strongest drawings in the show: an economical drawing of the mountain rising above a lake and single tree.

Hopper turns his attention to sailboats and cottages along the shore. He draws with quick, fluid lines that move across the page with the same ease with which his sailboats glide through water. Many of his drawings are compositional studies for paintings in which Hopper is concerned with the relationship between architecture and landscape. Some drawings are fully realized, but most are quick, offhand sketches.

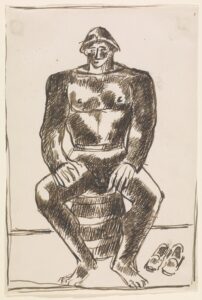

It’s inevitable to compare the two artists. Hartley’s drawings don’t read as studies like Hopper’s do but rather as artworks that existed parallel to his paintings. His range is impressive, from a Cezanne-like pencil drawing (Landscape With Forest Road) to dense, cramped ink drawings of fishing equipment (Fish Nets and Lobster Traps).

What’s significant about these artists is their way of integrating modern experience into seemingly straightforward drawings of landscapes and people. Hopper’s study of a nude woman (likely for A Woman in the Sun) renders the individual existentially exposed and unadorned. Hartley’s drawings of broad-shouldered, burly men convey a heaviness of existence and desire. Beneath the summery delight in these pictures is another layer of truth: one that doesn’t deny the pleasures of the quotidian or the pastoral but rather finds meaning in the rocks along the shore and in the lifeguards, cottages, sailboats, and fishermen that populate it.

The show is on view until Aug. 17. See paam.org. —Abraham Storer

Midsummer Music in Orleans

Joseph Haydn’s Piano Trio in C Major starts with a light conversation between piano, violin, and cello. Like people chatting over tea, the instruments trade banter and build on each other’s ideas politely. Published in 1797 with three movements — Allegro, Andante, and Presto — the piece is classical in structure. But despite the formulaic rules of the era, Haydn’s wit comes through in moments of overlapping melodies and dark turns of phrase. His sense of humor especially shines in the finale, where the instruments’ pleasant conversation turns into heated debate.

The trio is the first piece on the program in the fifth concert of the current season of the Meeting House Chamber Music Festival, which is on Monday, July 21 at 7:30 p.m. at the Church of the Holy Spirit (204 Monument Road, Orleans).

Also on the program are 20th-century composer Rebecca Clarke’s Two Pieces for Viola and Cello and Midsummer Moon for Violin and Piano and the finale of Carl Maria von Weber’s Quartet in B-flat Major. The musicians are violinist Joyce Hammann, cellist Megan Koch, violist Danielle Farina, and pianist and festival artistic director Donald Enos.

Clarke’s pieces are lyrical and atmospheric, bringing to mind the work of Impressionistic composers Maurice Ravel and Claude Debussy. With Von Weber’s quartet, listeners return to the world of traditional harmony — the quartet’s finale is a triumphant declaration interspersed with moments of serenity.

The program ends with Johannes Brahms’s Piano Quartet in A Major, Op. 26, completed in 1861. It opens with contemplative chords from the piano, followed by a meandering descending melody on cello before evolving into a dramatic, expansive quartet collaboration. The piece has four movements, and all have the lush, dark romanticism listeners expect from Brahms. It’s a masterpiece of emotion: the melodies are poignant, with stirring chords and an unexpected ending.

Tickets at the door are $25, with those under 18 free. See meetinghousemusic.org. —Eve Samaha

An Artist’s World of Whimsy and Connection

In Orestes Gaulhiac’s colorful paintings, currently on view at Galería Cubana (357 Commercial St., Provincetown), birds drift on the heads of wide-eyed figures. There are curious cats; colorful, striped hats; a sleeping moon; and a sun with exaggerated lips. Flowers populate the canvases in a rainbow of hues.

The world of Gaulhiac’s paintings is a gentle one, where the only goal is to appreciate the miracle of life. “For these paintings, Gaulhiac imagined himself to be in an ideal world,” says gallerist Michelle Wojcik. “One without fear, stress, or need for money.” The work is playful and theatrical, demonstrating the influence of the 10 years Gaulhiac spent creating set designs for children’s television.

Part of creating the serenity of this imagined world lies in an appreciation of nature and a desire to live in harmony with it. Birds, cats, plants, and humans are all given the same treatment and recognition. For Gaulhiac, this appreciation started as a child growing up in Santiago de Cuba, where he noticed the natural beauty around him.

Gaulhiac’s painting With One Flower, It’s Enough (Con una flor, es suficiente) is dedicated to the idea of simplicity: sometimes, a simple gesture is enough to create connection and contentment between two people. This simplicity is reflected in the flat geometric shapes Gaulhiac uses to render his subject. Through layers of acrylic paint and detailed crosshatching, he creates a sense of three-dimensionality, adding shadow, light, and texture.

But a little extravagance doesn’t hurt either in this whimsical world. In The Enchanted Vase (El florero encantado), flowers and birds of every color overflow the titular vase. Each face that looks upon this abundance has an avian companion returning the gaze: part of a magical connection between humans and the flora and fauna that surrounds them.

The show is on view until July 28. See lagaleriacubana.com. —Antonia DaSilva

A ‘Party’ of Queer Resilience and Strength

According to photographer and curator Quil Lemons, “AFP” (short for “American Faggot Party”), currently on view at Stanley (494 Commercial St., Provincetown), is not just a group show — it’s a “happening.”

Lemons calls the show “a declaration of resilience and liberation.” It features works by 13 contemporary queer artists and seeks to create a dialogue on diversity, identity, representation, and equality.

The show is Lemons’s response to the rise of American fascism. He says the idea for the project started to emerge after the Jan. 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol, which threatened the fundamental ideals of American liberty. Lemons conceived the exhibition as a means of establishing that queer representation is stronger than ever and here to stay.

In addition to Lemons’s own work, the show includes pieces by Drake Carr, Lyle Ashton Harris, Thomas Allen Harris, Oscar yi Hou, Papi Juice, Myles Loftin, Ryan McGinley, Slava Mogutin, Juan Antonio Olivares, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Diego Villarreal, and Ocean Vuong.

“As queer people, our community is always oppressed — especially now,” says McGinley in a recent interview in Cultured magazine. “I come back to the mantra, ‘No pride for some of us without liberation for all of us.’ It’s nice to shout this phrase with your comrades before a battle.”

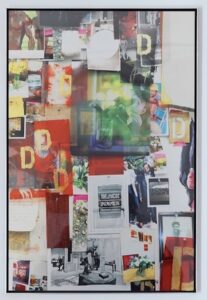

The works in the show express struggle and liberation in various ways. Lyle Ashton Harris’s collage Untitled (for Daddy I) includes photos of white lilies rising out of green glass vases. The shine of translucent green surfaces matches a glistening half-torso photo in the top left corner of the piece, while a stenciled letter D appears in gold repeatedly throughout the composition and a book cover of Richard Wright’s Black Power: A Record of Reactions in a Land of Pathos occupies the center.

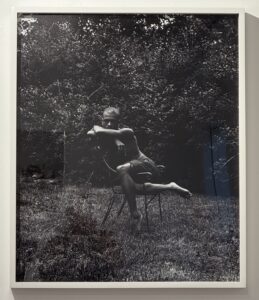

In Myles Loftin’s Untitled (Self-Portrait), sunlight catches the horizontal planes of the artist’s arms and legs as he sits sideways in a metal chair. Draped over one of the armrests, his left leg descends down towards the grass with his toes en pointe, like a dancer’s. Loftin gazes straight at the camera, his portrait a blend of vulnerability and strength.

The AFP project also includes a series of film screenings and artist conversations over the course of the summer, including a discussion between filmmaker Patrik-Ian Polk and Paul Glass, former board member of the AIDS Support Group of Cape Cod, on Thursday, July 24 at 6 p.m. The talk will be followed by a screening of Polk’s film The Skinny at Waters Edge Cinema. There is a $20 suggested donation for the talk and a $10 suggested donation for the screening.

The AFP exhibition is on view through Sept. 28. See 20summers.org for a complete schedule. —Pat Kearns