The screened porch of the house that eminent architect and designer Marcel Breuer built in Wellfleet in 1949, a box-like room cantilevered off the side of the house in such a way that it seems to float in the air and the room in which the family ate all its summertime meals, was going to come crashing down if the dining table was allowed to remain.

The original table was a 600-pound, two-inch-thick square of slate, balanced on six cement blocks. “It was structurally damaging the whole building,” says Peter McMahon, founder of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust. The trust bought the Breuer house, saving it from likely demolition, last July, and in one year McMahon has orchestrated a complex project of restoring the modernist structure.

For the porch, craftsman Jeff Soderbergh is building a replacement table of dark oiled mahogany, a lighter material.

Pacing in the sun outside the Breuer house on June 25, McMahon makes an announcement: a truck carrying mattresses is due to arrive in six minutes. Or, at least, that’s what the driver told him 10 minutes ago. They probably got lost, he says, trying to navigate the deeply eroded, sandy tracks that wind between Slough Pond, Herring Pond, Higgins Pond, and Williams Pond.

Trucks carrying important equipment keep doing that, he says: chickening out before they reach the house, which stands atop a slope overlooking Williams Pond.

Four days before the first-ever renters are to arrive, McMahon says, “We’re reaching peak chaos.” These last few weeks have been hectic, as everyone involved works to make up for time lost to winter weeks when frigid weather and tariff trouble slowed down construction.

The rental is a significant milestone for the trust, which seeks not only to preserve the houses it protects but to share them with an appreciative public — many of them art historians, architects, and students who want to “experience the architecture in a really intense way,” says McMahon. The place is booked through the summer, and the rental revenue will help support the work of the trust.

Inside the house, a quieter sort of chaos — different from the ringing of hammers, revving of pickups, and scrubbing of blades against wood — abides.

In the 1961 extension of the house called the studio, artist Bob Bailey rifles through a shifting stack of artwork, most of it high-quality reproductions of pieces found in the house when the trust acquired it last summer.

McMahon and Bailey first collaborated in 2006 when they curated a show called “A Chain of Events” at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum about the modern houses of Wellfleet. At the time, “most people didn’t really understand how many important modern houses there were around here,” says McMahon. “It started this real momentum.” In 2007, McMahon created the nonprofit with the aim of preserving them.

The studio, an airy room grounded by a large concrete fireplace, is where Connie, Breuer’s wife, hosted jazz parties, says McMahon. There’s an upright piano against the wall, covered in canvas to protect it from construction dust.

Bailey lifts up a print by Juliet Kepes: a graceful bird, maybe a pheasant, against a background the color of coffee. “Where’d you find that?” says McMahon. Bailey positions it above the piano. The two men consider it; they come to a sort of nonverbal agreement; Bailey puts it down again.

Even before the trust bought the Breuer house, McMahon began to remove items in collaboration with Breuer’s son, Tamás. “There were certain things that were valuable,” he says, “that were in danger from insects and mold.” Alongside the renovation, there’s been the painstaking work of archiving Breuer’s belongings, “books, art, photos, furniture, ceramics, ephemera,” says McMahon. In the first round of removal, he says, he consulted archivists who told him to “try not to throw anything away.” Who knew what could turn out to be important?

Sometimes it was difficult to tell. McMahon found an original lithograph by Paul Klee, dating from 1921, called The Saint of the Inner Light. It was attached to the wall with thumbtacks. He found another 1921 Klee stuck in a book. “An original, signed,” he says. “It had a coffee stain on it, and it was ripped.”

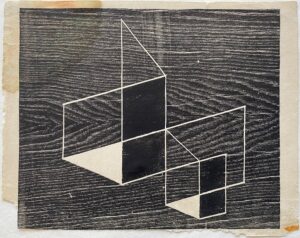

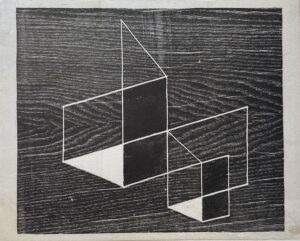

He found a Herbert Bayer painting from 1948 shredded. And there was a Joseph Albers woodblock print from the same year, High Up, which he found in an envelope. “Silverfish ate the margin where the signature was,” says McMahon. “It stopped when it got to the ink.” He enlisted Somerville paper conservator David Columbo to restore those pieces.

“Breuer revered Klee,” says McMahon. “They were close. Breuer really admired him as an artist and emulated him in some ways.” It’s not that Breuer treated the artworks with disrespect. It’s just that it was “buddy-art,” says McMahon, pieces given to him by artists who were family friends. “It was not precious in that it was almost like a birthday card that somebody sent you.”

The Breuer house was broken into at least three times before the trust bought it, says McMahon. But he says no one ever took anything of value. “They looked around and said, ‘There’s nothing here.’ ”

McMahon will put a reproduction of the Albers over Connie’s desk in the studio. He’s thinking of hanging one of The Saint of the Inner Light on the wall with thumbtacks, the same way the original was.

There will be a bed in the studio, opposite the fireplace, if the mattress is ever delivered. Bailey holds up two copies of pieces by Norman Ives, an acolyte of Joseph Albers, over the bed. “I think they’d be beautiful here,” he says. “Boom, boom.”

Bailey is adamant about not overwhelming the space with artwork. He wants blank walls, straight lines, empty spaces for light from the big windows to pool and spread. As for the works that he does hang, he says, “I want them to sing.”

Bailey and McMahon know one thing for sure: a large painting by Jack Hall will hang above the bed in the main bedroom. Hall, a self-taught Wellfleet architect and artist who created a welcoming environment for the European modernists when they arrived in the mid 1940s, lived on Bound Brook Island until his death in 2003. Hall studied to be a clown, says McMahon, and was known to lead Wellfleet’s Fourth of July parade.

The painting’s perspective is from inside a car: there’s the steering wheel, the side mirror, and the wide windshield through which the hood of the car is visible. In front of the car, a sandy road seems to wind on forever through a verdant dreamscape of beach grass. “You can tell it’s the road going out to Bound Brook because the marsh is on the left and the trees are on the right,” says McMahon.

Bailey holds the painting up: it looks good against the brown wall, he thinks. “It’s somehow super quiet up there,” he says.

Two years ago, McMahon described the house as “a fascinating shipwreck”: beautiful, full of secrets, but ruined. After Breuer died in 1981, maintenance on the house was scant. As the house rotted, says McMahon, “there was superfluous framing added that really detracted from Breuer’s original idea.”

Breuer wanted things to be crisp, says McMahon: the main building and the wings were supposed to appear to hover; the beams below were covered with creosote, so that they disappeared into the shadows. But as the building weathered and supports were added, McMahon says, “the building got kind of fuzzy.” Chunks began to fall off; the pergola plunged.

McMahon removed the fuzz.

When the pickup trucks go home, calm returns. The house floats again.

“In a way,” says McMahon, “it looks better than it ever did.”