Susannah Cahalan writes that Rosemary Woodruff Leary is “everywhere and nowhere.”

Her point is that the woman who was the fourth of five wives of Timothy Leary — the Harvard lecturer whose radical life captivated and headlined the psychedelic counterculture of the 1960s and ’70s — was more than his backup girl. She was an adventurer on many fronts and a co-creator of America’s psychedelic consciousness. “There’s a good chance you’ve seen her face dozens of times without ever registering her existence,” Cahalan writes.

In Cahalan’s new book, The Acid Queen: The Psychedelic Life and Counterculture Rebellion of Rosemary Woodruff Leary (Viking), she brings Rosemary out of Timothy’s shadow and into the light.

The book chronicles a life that takes some strange turns. Rosemary Sarah Woodruff was born in 1935 in St. Louis. While still a teenager, she had a short-lived marriage to an Air Force officer named John Bradley. She was a model, a stewardess, and an actress. After moving to New York in her early 20s, she began using LSD. She went on to spend a significant part of her life experiencing an alternate reality induced and shaped by the drug.

The book has a feminist angle because it’s about Rosemary instead of her more famous husband and also because “Rosemary provides a perspective on the underground women’s experience of psychedelics,” says Cahalan. “It’s been glossed over by a very medicalized view — this is typically also a male-dominated view. Rosemary and a lot of women of the underground accrued a knowledge that you couldn’t include on a research paper but is very important to the understanding of the psychedelic experience as well as understanding the brain and body.”

In 1967, Woodruff married Leary, a Harvard researcher and proponent of LSD. She helped take care of Timothy’s children and backed him up when he had brushes with the law. When Timothy led group psychedelic experiences, Rosemary’s role was to facilitate the “set and setting” — creating an atmosphere, moving furniture, providing food, music, and comfort — for their successful acid trips.

This “caregiver” life was not without drama. People jumped out of windows on LSD trips encouraged by Timothy. His daughter stuffed drugs into her underwear when the family car was stopped by the police. Rosemary, too, rushed to hide evidence of drugs many times. In 1970, after several run-ins with the law, Timothy was sentenced to 20 years in prison. Rosemary teamed up with the militant Weather Underground to help Timothy escape. The couple fled to Algeria to live at the Black Panther embassy.

Even after she separated from Timothy in 1972 and they divorced in 1976, Rosemary’s life was affected by her famous ex-husband’s. Rosemary, too, had broken the law and was on the run. Her refuge: Outer Cape Cod, where she lived for 10 years under an assumed name, Sarah Woodruff.

During her research for The Acid Queen, Cahalan came across Kathy Shorr’s 1997 Provincetown Banner article, “A Public Secret, Finally Revealed.” Shorr didn’t out Rosemary — the article was published after Rosemary had moved to California and re-adopted her name. “When I found that article in the New York Public Library archives,” Cahalan says, “I thought, this is a book.

“The Cape Cod chapter of her life has never been written about before,” Cahalan says. For Rosemary, this was a place to hide, she says, but also to find herself again. “I love this idea of her getting her life back and finding a new identity as Sarah.”

Cahalan visited the Provincetown Inn, where Rosemary had worked. She walked by the places Rosemary had lived in Provincetown, Truro, and Eastham. She searched out old friends of Rosemary’s who are still here. “I walked in her footsteps on the Cape,” says Cahalan.

The NYPL’s archives proved an invaluable resource. Cahalan spent a year going through them: 25 banker’s boxes of primary source material including multiple drafts of a memoir that went unpublished during Rosemary’s life, diaries, tax returns, day books, and Christmas cards.

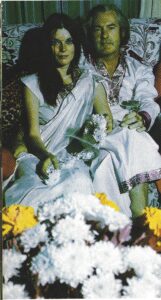

In 1992, Rosemary reclaimed her previous identity and reunited with Timothy. In spite of her complex feelings about him, she found that their passion for each other had survived. “With him, holding him,” Cahalan writes, “she remembered his humor and joy; how he filled the space with a great balloon of his enthusiasm.” The book covers their reunion and their end: Timothy died of cancer in 1996, and Rosemary’s death came in 2002 from congestive heart failure.

At the end of her life, Rosemary had mixed feelings about her lifelong use of LSD. When she was invited in 2001 to give a lecture at the University of California Santa Cruz, she told the students that they must prepare to engage with both the light and the shadow if they chose to use the drug.

“It made me aware of another reality than this reality that we experience in our daily lives,” Rosemary said. “We have blinders on and don’t pay attention to it.” Because of the drug, she said, “I’m more inclined to pay attention to beauty.”

What becomes clear in The Acid Queen is that Rosemary spent years searching for an identity that was truly her own. She “provided the scaffolding for another person to go off and shine,” says Cahalan. But who was Rosemary without Timothy?

The book suggests an answer. The experience of awe that she discovered through LSD as well as her warning to the younger generation of its perils are parts of a legacy of Rosemary’s own.