Photographer and filmmaker Thomas Allen Harris founded Digital Diaspora Family Reunion (DDFR) in 2009 as a vehicle for audio-visual events incorporating community organizing, performance, virtual gathering spaces, and storytelling. Ten years later, Harris, who teaches at Yale, brought DDFR to national TV with Family Pictures USA. Originally conceived as an exploration of how African Americans appear in family albums, DDFR grew into an international cultural initiative, with Harris leading workshops across the globe.

People bring their own archival family images to these workshops. Harris and his crew help them digitize 15 to 20 photographs and tell stories about them. The process is captured on film, narrated by family members, and guided by Harris. He has documented 75 of these workshops in Brazil, Canada, and Ethiopia, and in 65 American cities. (Many of the documentaries can be viewed online.)

Harris is bringing his workshop and documentary model to Provincetown as part of the Twenty Summers series. He will lead a “Queer Ancestors” storytelling workshop at the Hawthorne Barn on Saturday, May 31. Participants will bring photographs of a queer ancestor or mentor, and Harris will guide the group in storytelling. He says he hopes a “metanarrative” will emerge.

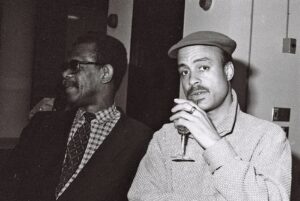

In a separate exhibition, “House of Haizlip,” curated by Sonnet Carter, Harris will show 10 45-by-60-inch black-and-white photographs taken in the late 1980s of his experiences with his own queer ancestor and mentor, TV producer Ellis Haizlip. Haizlip created the groundbreaking public television show SOUL! from 1968 to 1973, which helped introduce the Black Arts Movement to a wider audience. Haizlip also produced the famous 1971 conversation between author James Baldwin and poet Nikki Giovanni.

Harris’s photographs of Haizlip were taken during events Haizlip produced at the Schomburg Center for Research on Black Culture at the New York Public Library. One of the photos in the exhibition, which will be mounted at Stanley, the Twenty Summers annex at 494 Commercial St., is of the Black gay men’s writing collective “Other Countries,” founded in New York City in 1986.

Harris and Haizlip met in 1984 through their mutual friend Henry Chin. “I was in my early 20s, and Ellis was in his mid-50s, producing shows with Alvin Ailey,” says Harris. The two became lovers after Harris moved to Paris in 1985. They stayed close until Haizlip died in 1991 of lung cancer.

“Ellis was my mentor,” says Harris. “He was an openly gay cultural leader. It was difficult seeing his health decline so precipitously during a time when we were also losing so many friends to AIDS.

“During Ellis’s final months,” Harris continues, “my relationship with my Spanish boyfriend, Miguel, was also coming apart, and he was preparing to leave and move back to Spain. It was during this time of impending loss that I purchased my first Hi-8mm video camera and began setting it up and speaking directly to the camera as a form of therapy.”

It was October 1990. Harris confessed to the camera that he didn’t want to move to Spain with Miguel. “I wanted to remain in New York to pursue a career,” says Harris, “even though as an emerging Black queer filmmaker, I didn’t see images of myself or my community portrayed in media.” These video diaries will be included in the exhibition at Stanley.

Harris told the camera he was committed to remedying this absence through his work and that somehow he would find a way to do it. “Videotaping myself and teaching my community how to use the camera to create images of ourselves became a hallmark of my practice as an artist and filmmaker,” he says. “When you share an image in public, you might have something in mind, but your heart has a story or song that’s also there and comes out in ways that are unpredictable.”

Harris’s Queer Ancestor Workshop is part of his documentary practice. Participants are invited to share images of people who have guided them at pivotal moments and shown them what’s possible.

“I thought it would be a good historical moment to celebrate us,” Harris says, considering the current backlash against trans people and the rolling back of LGBTQ rights. “It will be important to celebrate and affirm who we are.”

Harris was born in 1962 and raised in the Bronx. He spent time in Tanzania as a child because his mother, Rudean Leinaeng, was teaching there. Leinaeng was a chemistry professor at Bronx Community College for more than 30 years. She is the subject of Harris’s latest film, My Mom, The Scientist.

His late stepfather, B.P. Leinaeng, worked at the United Nations as a journalist in the anti-apartheid division. He and 11 of his comrades left their home in Bloemfontein, South Africa in 1960 to support the African National Congress and Nelson Mandela. Harris captured his stepfather’s story in the 2005 award-winning documentary Twelve Disciples of Nelson Mandela. Harris’s mother and stepfather both went to graduate school at NYU. They started vacationing on Cape Cod in 1980, just as Harris entered Harvard College. He graduated with a degree in biology in 1984.

Harris was a producer at WNET, New York’s PBS affiliate, where he made Emmy-nominated programs about HIV-AIDS activism and the culture wars of the late 1980s for the station’s public affairs shows.

“We did one show about artist Karen Finley,” he says, “and one on Radical Reverends — an initiative by ministers who were painting over alcohol signs in Harlem.” Harris came out “politically,” he says, during those early years in public television. He points to productions like “Day Without Art,” a 1992 segment he produced for The Eleventh Hour that covered artists’ efforts to confront the AIDS epidemic in the absence of mainstream media coverage.

Harris’s brother is American artist Lyle Ashton Harris, who works in photography, collage, installation, and performance art. The two frequently collaborate.

Harris’s films include Through a Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People (2014), which won an NAACP Image Award, É Minha Cara/That’s My Face (2001), and VINTAGE — Families of Value (1995). His PBS series Family Pictures USA (2019) expanded his exploration of how family photographs can illuminate broader historical narratives.

Harris is a professor of film and media and African American studies at Yale. His Family Pictures Institute, with the New York Hall of Science, won a $3.2-million grant from the National Science Foundation last year to support Scientists in the Family, a national documentary storytelling project highlighting participation of Black and underrepresented communities in science.

That grant was just rescinded in the administration’s campaign against diversity, equity and inclusion.

Harris had launched the Family Pictures Institute for Inclusive Storytelling at Yale in 2021. “I’m happy Twenty Summers was on the radar, because I’m doing what I love to do — storytelling and working in this way,” he says. “It’s a strange new landscape we’re in, but we can do this — that’s why Twenty Summers is so important, because it allows artists to strip down everything and come with the purity of our art.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article, published in print on May 22, incorrectly identified a group featured in a WNET program as “Radical Reverence.” It was called “Radical Reverends.” Also, the National Science Foundation grant for Scientists in the Family was to support a national documentary project, not one documentary film.

Queer Ancestors

The event: Storytelling workshop with Thomas Allen Harris

The time: Saturday, May 31, 1 p.m.

The place: Hawthorne Barn, 29 Miller Hill Road, Provincetown

The cost: Free (registration recommended)

‘House of Haizlip’

The event: An exhibition of photography and video by Thomas Allen Harris

The time: Opening reception Wednesday, May 28, 6-7:30 p.m.; on view May 29-30, noon-4 p.m.

The place: Stanley, 494 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free