Commercial Street in Provincetown is a theatrical place. In the summer, it’s filled with drag queens, street performers, and colorful characters. Similarly, many of its buildings embody outsize personalities. There’s the red-orange glow of the neon signs at the Lobster Pot. In the West End, Spiritus Pizza looks and smells enticing with its hand-painted signage, brick patio, and aroma of tomato sauce and fresh dough wafting through the air.

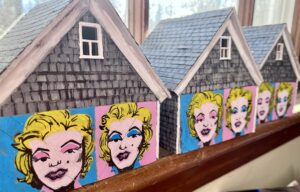

For Brewster artist Elizabeth Kirby, those two restaurants were ideal subjects for her growing collection of miniatures. “I think of each miniature as a theatrical stage set where someone just walked off,” she says. Her pieces are devoid of people. Rather, she focuses on the idiosyncratic details of each building. The sculptures, no more than one or two feet long on any dimension, are reminiscent of set design mockups or the buildings and scenes that populate a model train setup.

Kirby started the miniatures project last year when her mobility was restricted because of illness. “It’s about approximation,” she says. “I want to capture the emotional feeling someone has when they’re there as opposed to being completely accurate.”

Initially, Kirby built her miniature buildings from recycled household materials. Now, she selects her materials with an eye to longevity. In her miniature of the Lobster Pot, she painted balsa wood for the structure and used plastic film for the windows. The shingles are cut from paper. The irregular pattern of the shingles on the second story reflects Kirby’s fascination with subtle details. She uses thin fiber filaments to approximate the Lobster Pot’s signature red lighting.

Kirby uses a 3D printer to make molds for pieces she needs a lot of, like the brick walkways around Spiritus. It was the brickwork that initially got her interested in making the Spiritus miniature.

She starts with the basic structure of the building, and then, to find the right scale for the details, she picks one element — a window or door — and creates everything else based on that. She relates this process to the many years she spent as an event designer and florist — starting with the largest element and then working down to the little parts.

Kirby, who grew up in Needham, says she knew she wanted to be an artist from a very young age and also loved crafts. Her grandmother was a children’s clothing designer for Carter’s and encouraged Kirby’s crafting. At art school, the emphasis was on separating craft from art, a distinction she says she doesn’t find meaningful. She attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Penland School of Craft in North Carolina before completing her studies at Pratt Institute in New York.

In 2019, after living in Brooklyn, Kirby and her husband, who is also originally from Massachusetts, decided to return to their home state. They chose Cape Cod because of the Provincetown art scene. “It’s the best art scene in New England,” Kirby says. She shows her work at AMZehnder Gallery in Wellfleet.

Kirby’s miniatures sit at the intersection of craft and fine art. In her career as a florist, she realized that the line between the two was blurry. “I was essentially making sculptures,” she says. The different aspects of her work didn’t have to be compartmentalized, she concluded. The history of miniatures, likewise, inhabits an ambiguous territory. Humans have long reinterpreted the world around them on a small scale. Ancient Egyptians created miniatures for the tombs of pharaohs — a way to bring their life on Earth with them to the afterlife. The dollhouse is a more recent variation, popularized in the 18th century to teach girls how to manage a household.

Kirby’s sculptures reflect an increasing interest in the handmade. “People want an object,” she says, noting a contemporary reaction against digital art and AI. “They want to know that you touched it and that there’s humanity behind it.” The rise of platforms like Etsy and Pinterest have also encouraged the emergence of the handmade. There, anyone who has the desire to make something can share it with the world.

Kirby’s work carries an inherent connection to place. For years, she has been a graffiti artist — work that’s about site specificity and immediacy, she says. While the miniatures don’t try to capture a specific moment in time, they are certainly site specific. They preserve a moment in the life of each building.

Kirby wants her project to expand and continue. She would like to create miniature versions of historical buildings in Boston that could be displayed on pedestals at the actual buildings. She sees her project as a way to build community by connecting people over their experiences of a shared place.

After she showed her version of Spiritus Pizza at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum in a members’ open show, people contacted her. “The best part about it was that I kept getting emails from people telling me what Spiritus meant to them,” says Kirby. “I knew it was an important part of the community, but to have it laid out for me was wonderful.”