Janice Redman, a sculptor, and Elizabeth Bradfield, a poet, are neighbors in North Truro who have worked together for the past 15 years. “She sits in this chair and works on her laptop,” says Redman, gesturing to an armchair in her studio. “I give her a little sheepskin rug in the winter and a pair of slippers I got at Mass Appeal.”

They start off by chatting for a few minutes. Then they set an alarm for 30 or 40 minutes and get to work. “When the alarm goes off, we get up, stretch for a couple of minutes, maybe get some water,” says Redman. They repeat the pattern for three or four hours, sometimes for a whole workday, and then go for a swim or a walk. “We swim together more in the winter than in the summer,” says Bradfield.

Bradfield often reads aloud to Redman poems she’s writing. “Putting the words out there in the room and being aware of another body receiving them changes the way I hear them,” she says. “It feels like a promise to the poem. If I voice it, it’s becoming something real, instead of just hiding in the notebook.”

Bradfield often writes about the natural world, but, as Nicky Beer wrote in a 2008 review of Bradfield’s book Interpretive Work, this outward-focused perspective “inevitably boomerangs back to remark upon the desires and motivations of the human observer.”

Redman’s sculptures are made with an assortment of materials including honeycombs, hot water bottles, pins, and fabric. When she had a broken toe last year, Redman worked mostly at her desk creating white doll-like figures stuffed with sand that she arranged in interlocking hexagons. The piece, titled Legacy, is an homage to her mother, who died four months ago and was a prolific maker of lace, embroidery, quilts, and clothes.

“My mum taught me everything,” says Redman, who employs methods associated with domestic craft into her sculpture. She had written something about her mother to accompany the piece — Bradfield took the text and created an erasure poem, which is now stitched onto the dolls.

Redman grew up in South Yorkshire, England and came to the U.S. for artist residencies, first at the Core Residency Program in Houston and then at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown. When her son was born, she took a break from making art, aside from creating toys for him. When he started school, Redman was ready to begin again.

At that same time, Bradfield had recently returned to Cape Cod after a two-year Wallace Stegner Fellowship at Stanford University. “Both of us were at a transitional moment,” says Bradfield. She was questioning her next steps: “How could I continue to make work without the support of that fellowship? What would be my artist community?”

Redman often spotted Bradfield jogging by her studio. They didn’t know each other well. Redman invited Bradfield for tea, but the poet had a different idea: “parallel play” — doing separate things together. “It gave me discipline and self-esteem after not having worked on my art for a pile of years,” says Redman. “It was a really nice way to start again.”

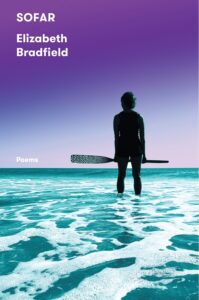

Redman’s intimate sculptures are currently on view in a solo exhibition, “Rough Alchemy,” at Bookstein Projects in New York City. Bradfield has a new book of poetry, Sofar, scheduled for release by Persea Books in August. These projects are not exactly collaborations, but it’s become difficult to disentangle their parallel play from their joint efforts. “There’s always a sense of collaboration, a to and fro,” says Redman.

One of Redman’s recent sculptures was made by stitching wool around a wooden oar, covering it with glue, sanding it down, and then boring holes of various sizes into the paddle. It’s a familiar object but completely reimagined in terms of material and purpose. The stitches on the back of the oar reveal Redman’s handiwork. “That idea of making labor visible and making that be part of the emotionality of the pieces is one thing I really like about her work,” says Bradfield.

Bradfield titled Redman’s piece Feathering, referring to rotating an oar so that the blade doesn’t catch air when it’s above water. A feather also seemed like a fitting metaphor: “They are light and delicate, yet so strong,” says Bradfield. “It just felt right for that piece, which is both strong and vulnerable.”

Bradfield comes up with titles for most of Redman’s sculptures. “It’s like making a poem for the art,” Bradfield says. “You have to think about a title that’ll be suggestive and open up different avenues but also reflect the emotional truth of a piece of art.”

As the founder and editor of Broadsided, a digital publishing project where artists and poets collaborate, Bradfield thinks about the intersection of words and images. “I like it best when the words are not just a caption for an image but when they’re both present and can both do their own thing,” she says. “How do they create energy? How do they amplify each other?”

In a poem in her new book, Bradfield writes about Feathering but offers it a new title: “Memory Rowing the Passage of Time.” The oar becomes a symbol of time and memory. The poem ends: “…Each day,/ there are little moments I can’t reach back/ and touch, which makes it easier to pull/ the oar. Which makes it harder to get anywhere.”

In addition to inspiring a poem in Sofar, Feathering is also featured on the book’s cover. Bradfield is photographed in silhouette, holding the oar while looking out at the ocean. “The idea of an oar is something that gets you somewhere on the water, but the way that she’s changed it has made it incredibly fragile and delicate and a little scary,” says Bradfield.

To create the photograph, Bradfield needed to stand in water with the oar. Like their broader creative partnership, this collaboration was an act of trust. “It was scary because if that thing gets wet, it’s ruined,” says Bradfield. For Redman, “It was a risk, but it was worth it. And luckily, she has better balance than I do.”

Memory Rowing the Passage of Time

By Elizabeth Bradfield

—after a sculpture by Janice Redman

is what I’d title this piece, if asked. And

this is what my new mind, which is an older

mind, feels like: an oar with the blade

so thoroughly drilled it’s more hole

than wood. I’m reading about different

cultures of time — linear (the past

behind you), visible (future

at your back), vertical (time falling,

your body an hourglass), coiled

(loops touching again and again).

Janice has covered the oar in something

like moleskin, which was never

the skin of a tiny, shy mammal, but heavy

cotton roughed to softness. I like hacks

for anticipated wear. One spring, I sewed

leather cuffs onto our skiff’s oars, pushed

waxed twine through punches with a sailpalm,

which made me ridiculously enamored

of myself, sitting in the sunlit drive, thinking

if only someone could come by and see this, they’d

have to fall in love with me. Janice’s oar hangs,

vertical, braced by a special-made mount. If

it dropped, it would break, but my heart’s not

in my throat. One version of time

is a circle, Ouroboros, the world’s waters

held inside, everything inside, held. Each day,

there are little moments I can’t reach back

and touch, which makes it easier to pull

the oar. Which makes it harder to get anywhere.