Rachel Brown remembers arriving on the Outer Cape as a child in 1944. Her family had moved from New York and rented a cottage on Slough Pond in Truro. “It was the largest body of water I had ever seen,” she says. “It was so huge, I couldn’t imagine swimming in it.”

Brown has focused her attention as a photographer on moments like that. She has traveled far from home to create images that convey the feeling — for her and the viewer — of seeing something for the first time. A sense of poetic wonder ripples through her revelatory black-and-white photographs.

Brown grew up in Wellfleet among artists and writers. Her parents, novelist William Slater Brown — who appears as the character “B.” in E.E. Cummings’s autobiographical novel The Enormous Room — and dancer Esther Rosenberg, had met through bohemian cultural circles in Greenwich Village. On the Cape, the family continued to expand its network. Artist Mary Hackett became Brown’s godmother.

Despite this wealth of creative influences, Brown didn’t pursue the arts until she was 40, after rearing her children. It felt natural for her to choose a creative career.

“I certainly wasn’t going to be a businessperson,” she says. “I was surrounded by artists all my life, so I easily fell into it.” She learned her way around a darkroom from Elspeth Halvorsen in Provincetown and later audited a photography class at M.I.T. taught by another friend, Melissa Shook. “The training I got in photography was from my friends who were kind to me,” says Brown.

In 1976, she visited Ireland for the first time. In a 2012 interview in Transatlantica, she said she felt drawn to the landscape after seeing a photograph of the coast of County Kerry. She continued visiting and moved to Northern Ireland in 1992. A year later, she met Daniel Dejean, now her husband, at an arts center and eventually joined him in his native France. The two lived in Toulouse for 14 years before settling in Wellfleet in 2010.

Brown hasn’t made photographs in Wellfleet, in part, she says, because she’s never been able to find a way into landscapes that she finds “too familiar.” There’s also the legacy of other artists, many of whom Brown knew, who mined the local scenes for their creative work. “I always felt inadequate trying to take pictures of this place, which I love more than almost anywhere in the world,” says Brown.

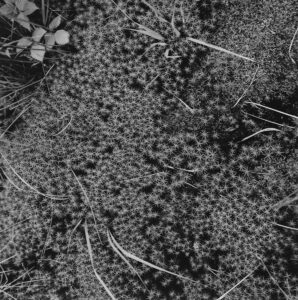

Sitting in her sun-drenched living room on a frigid winter day, Brown flips through some of the books she has created since taking up photography. The viewer vicariously travels with her in these photographs. She directs our eyes downward to a patch of heath moss as if we’re on a walk with her. In Donegal, on Ireland’s northwest coast, she introduces us to stone ruins, local characters, sheep markets, and turf, which she documents being cut and dried. “These photographs lie at a tangent to the accepted tourist view of Ireland,” wrote poet Ciaran Carson in his introduction to Brown’s book The Donegal Pictures.

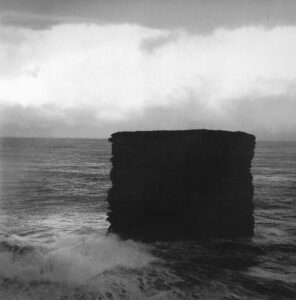

To look at Brown’s photographs is also to travel into her imagination. When editing her work, she says, she would look for images that conveyed “a kind of introspection” or atmosphere of the place. The photographs conjure the meditative experience of being arrested by a peculiar detail in a landscape: the strangeness of a form, like a monolithic stack of earth rising from the sea in Dún Briste, a Sea Stack. Her photograph of a tree laden with apples is a scene familiar to a New Englander, but she reimagines this motif in a tightly cropped image on black-and-white film so that the tree and apples appear almost like a sculptural frieze or an illustration from ancient literature. It’s at once familiar and universal, of the Earth and of a collective cultural imagination.

For Brown, poetry has served as a guide and inspiration. “If a photograph didn’t have any poetry in it, it wasn’t of any use,” she says. In 1992, she collaborated with Seamus Heaney, an Irish poet who at the time was living in Cambridge and teaching at Harvard, to publish Sweeney’s Flight. The book pairs her photographs of Ulster, a historic province of Ireland, with extracts from Heaney’s translation of a medieval Irish tale. (Brown had a different last name, Giese, when the book was published.) “I was responding to his poetry, which I love so much,” she says. “We’d get together and have lunch in Cambridge. I would spread out all these photographs, and we would pick out the ones we thought were meaningful in some way.”

In a later book of photographs, Solstice, Brown enlisted poet Mary Oliver, also a friend, to write an introduction. “To see such wildness balanced, as it must be at winter solstice and summer solstice, is Rachel Brown’s purpose and her achievement,” wrote Oliver. In one photograph from the book, Man Standing Before the Waves, Brown depicts Dejean at the shore’s edge, dominated by the expansive space and crashing surf. “I have seen the figure of a man at the edge of the waves — a better measurer of things than any foot-rule anywhere,” wrote Oliver of this image.

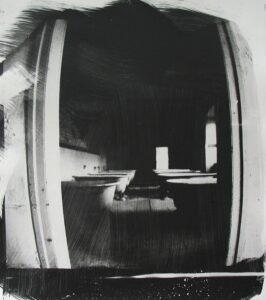

Brown’s first subject was eggs. “They were just something at hand,” she says. Some of her subjects are darker and the resulting images heart-wrenching. Her last project was something much further afield. She photographed the women’s wing of an abandoned asylum in Saint-Lizier, France. For these pictures, she enlisted pinhole photography and a new mentor, Marian Roth. This technique — along with the gestural quality of the printing process — casts a ghostly atmosphere over the space, referencing its dark past. “It was so spooky, and I was thinking of all these poor women who were probably just troublesome, and their families couldn’t deal with them,” says Brown. The photographs of rows of bathtubs, empty rooms, and a single chair by a window tell a story.

Brown’s career as a photographer has co-existed with major changes in the artform. When she was starting out, “People were still quite disdainful about considering photography as art,” she says. It has since gained status, but digital photography has widely eclipsed film photography.

“I wasn’t at all interested in digital photography,” Brown says. “I’m not saying it’s not good, but it’s not expressive in the same way.” In her photographs, the texture and literary quality of a film photograph is of primary importance.

“Black-and-white photography is like reading,” she says.