On a long wooden table in the quiet confines of the Cobb Archive in Truro, the beasts don’t circle as much as they overlap, still menacing but yellowed with time. They are flattened to two dimensions, disinterred from the stories they once illustrated, and frozen in a moment where perseverance or annihilation might stand equal chances.

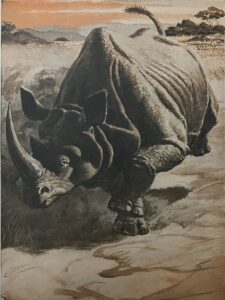

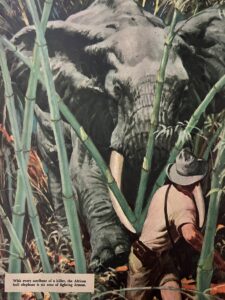

The rare rhinoceros charges across the dust. Trumpeting elephants trample jungle underbrush. A lion leaps into a red truck that has a flat tire. Six men stumble into surrender. Always, in each frame, a shotgun looms, in someone’s hand or within reach. The viewer watches a hunter watching his prey, uncertain of which is which. The tension hums.

“Coolly, almost contemptuously the hunter kept advancing,” wrote John E. Carlova in the October 1954 Adventure magazine story, “The Man Who Hated Rhinos.”

“The baked earth of the lake bed shook as the bull rhino started his charge,” he continued. “At first he moved awkwardly, head up, gait shambling. Then his head came down, his great horn pointing at de Charcourt, and he pounded his tremendous hulk along….”

No shot is fired. The story ends mid-sentence, its climax lost to the Adventure archives. This unresolved struggle deepens the existential themes that Courtney Allen’s illustrations evoke. Man confronts nature, confronts himself, and is left stranded in the act.

Allen hasn’t exactly been forgotten. But while his good friend and contemporary Norman Rockwell still makes appearances in America’s collective imagination of mid-century, Allen’s work has been largely boxed away.

Here, in the Truro Historical Society’s paper collection, dozens of his illustrations are preserved. Allen, in his later years, was the society’s co-founder and first president.

Volunteer Cathy Skowron, who lives in Truro, has spent the last couple of months sorting through two boxes of them, clipped or torn from old issues of the Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Cosmopolitan, Field and Stream, and Outdoor Life.

“He was definitely prolific and versatile,” said Skowron. “But you have no context for where it came from, no dates or anything.” To reconstruct that context without an archivist’s expertise, she examines the contemporaneous photographs also housed in the archive. Allen posed people to inform his painting and illustration.

“There’s a lot of action stuff,” said Skowron. “Big white hunters in Africa, Northwest explorers and fishermen, and a lot from World War I and II.”

On the surface, Allen’s illustrations are straightforward: they sell stories and the magazines that published them. Beneath the surface, though, they’re unsettling. Like the historical dioramas Allen later built, his illustrations both idealize and confront the past.

Allen was born in Norfolk, Va. in 1896 into successive upheavals. As the new century dawned, his parents split, and he moved from Ohio to Tennessee to Washington, D.C. working odd jobs before World War I began.

In D.C., he saw an exhibition of illustrated Saturday Evening Post covers, including one for a story by adventure writer Jack London. He’d found his calling: he enrolled in night courses at the Corcoran School of Art.

“He bought paint and brushes and academy board and went to work and made stories in pictures of anything and everything he could think of — western characters, men frozen in snow in the Far North, anything that told a story,” Leah Early wrote in a 1950 catalog for the Manor Club of Pelham, N.Y., which exhibited Allen’s oil paintings.

In translating three dimensions into two, Allan often carved wooden animals or photographed live models to study the angles, shadows, and tricks of light he then meticulously replicated with oil and watercolor.

Allen’s connection to the Outer Cape began when he was in his 20s. After serving with the Camouflage Corps in France in World War I, he arrived in Provincetown in 1919. To fund his art studies here, he and some friends from the Beachcombers Club ran the Sixes and Sevens coffee house — the town’s first nightclub — on Lewis Wharf, in a shed owned by Mary Heaton Vorse that had been recently vacated by the Provincetown Players.

“In addition to waiting on customers, we all played musical instruments and sang,” Allen told the Worcester Sunday Telegram in 1955. “We were our own floor show. Some nights there were long lines of people who just couldn’t get in because of the throng ahead of them.”

Allen met his wife, the illustrator and ceramicist Erma Paul, at Charles Hawthorne’s Cape Cod School of Art in 1921. Though they settled in New Rochelle, N.Y., where Allen founded the Huguenot School of Art, the couple returned to the Outer Cape often, drawn by a coterie of artist friends that included Jerry Farnsworth, John Whorf, and Edward Penfield. They bought a house in North Truro in 1927 and had one daughter, Charlotte Elizabeth.

From the 1920s to the 1950s, Allen’s illustration career flourished. His work captured the contradictions of America on the brink of the mid-20th century as it seesawed between power and precariousness. The illustrations awakened longing for a time when humans believed they could tame nature, when the struggle was with the dense forest or sprawling plain — not the bank account, the desk job, the threat of nuclear war. The rugged men facing wild animals were a fading ideal of white masculinity, united against a common enemy.

In an undated interview with the New Bedford Sunday-Standard Times, Allen said he preferred to focus on “outdoor stuff” over “he and she stuff.” The women in Allen’s illustrations rarely appear passive. They ride horses, wield shotguns, and stare down men with unnerving composure. These subtle challenges to the dominance of white men undercut the overt bravado of the adventure tales Allen illustrated.

Allen worked across mediums and materials, even venturing into eggshell caricatures. His friend John Whorf told the Worcester Sunday Telegram, “Anything Courtney Allen does, he does well.” As W.L. Francis put it in “The Incredible Mr. Allen” for Yankee Magazine in 1966, “You can’t take him in all at once.” Deborah Minsky described him as “Truro’s own renaissance man” in the headline of a 2005 article in the Provincetown Banner.

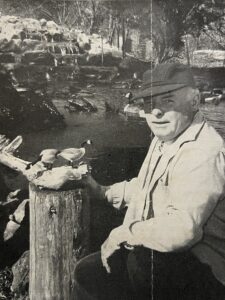

After moving to North Truro in 1951, Allen produced hundreds of carved miniature waterfowl, working from live models in the duck pond he designed and stocked on his property. He also built historical dioramas and replicas of a 19th-century glass factory, Lewis Wharf, and a 20-foot Mayflower to commemorate the Mayflower Compact’s 350th anniversary.

“In view of the earlier, highly perceptive renderings of reality, the transition to carvings of waterfowl and documentary models was a natural one,” wrote Susan Kurtzman, the former curator and director of the Highland House Museum, in 2005.

The Highland House Museum has the glass factory on display in the Courtney Allen Room and the Provincetown Museum has the wharf and the Mayflower.

Allen died in 1969, but his illustrations endure, their existential unease intact. In them, the hunt for identity persists, as wild and elusive as the beasts he rendered.

The prize buck plods through virgin snow. As that story begins, “It’s a curious thing how certain hunting episodes will haunt a fellow through the passing years while others fade fast into the blissful oblivion of forgotten memories.”