Bob Thompson came to Provincetown in 1958 and met a group of peers who would influence his art and his life. “I Am Myself: Early Works by Bob Thompson and Friends,” a recent exhibition at Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects in New York City, displayed his early work next to that of the friends and mentors he met that summer, illuminating the connecting threads between the artworks and the artists. He died in 1966 at age 29, and recognition of the significance of his work has only increased since then.

Thompson was born in 1937 into a middle-class African-American family in Louisville, Ky. He attended the University of Louisville in the late 1950s, where he was taught by painter Ulfert Wilke, a German refugee, and artists Mary Spencer Nay and John Frank. Both Nay and Frank were native Kentuckians who had studied in Provincetown.

In 1958, Frank urged Thompson to spend a summer in Provincetown as a student at the Seong Moy School of Painting and Graphics. Frank helped Thompson secure a scholarship and arranged for him to rent a place from the Roach family, who operated a cottage colony at 24 Conwell St. and were also Black.

Thompson quickly found his people in town through the art school and through friends of friends. The Steven Harvey exhibition included the work of Emilio Cruz, Red Grooms, Lester Johnson, Mimi Gross, Mary Frank, Jay Milder, Gandy Brodie, and Bill Barrell.

A work by figurative expressionist Jan Müller was also included, although he died six months before Thompson arrived in Provincetown. His striking totem-like painting, with grimacing faces, cavorting figures, and horses likely appealed to Thompson’s budding interest in expressionism. It’s easy to draw a line between Müller’s work and the painter Thompson would become, with his use of imaginative color and evocative narratives involving people and animals.

Thompson’s paintings in the exhibition aren’t fully representative of his mature work, but they do capture the ferocity and freedom with which he moved paint across a surface and his general disregard for sentimentality or fussy refinement.

Among the artists in Thompson’s circle who studied with Hans Hofmann, these qualities were common. But what set Thompson and his contemporaries apart was their commitment to the figure. He and his peers eschewed traditional approaches to figuration for something as bold and expressive as any of the abstract paintings being made at the time.

Provincetown’s Sun Gallery was an incubator for this group of figurative expressionists. Run by artist Yvonne Andersen and her husband, poet Dominic Falcone, the gallery operated from 1955 to 1959 with the intention of showing new artists. “Müller’s art remained a center of gravity for artists drawn to the Sun after his death,” wrote art historian Judith Wilson in a text accompanying a Bob Thompson exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

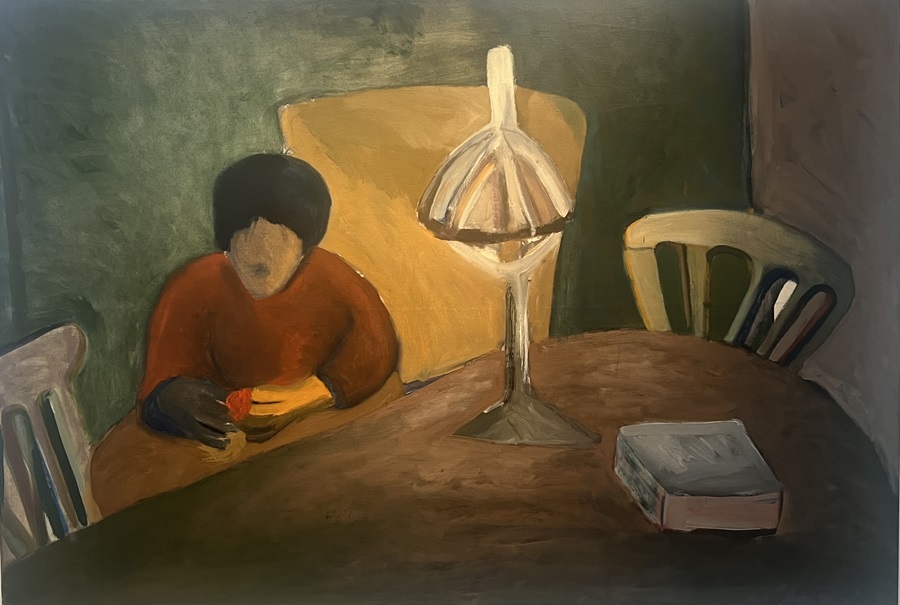

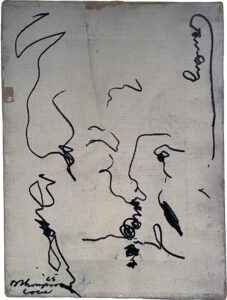

In addition to highlighting the stylistic overlaps between Thompson and his contemporaries, the Steven Harvey exhibition showed how the artists were muses and models for each other. In one painting, Thompson depicts Grooms in murky red and green. In two line drawings done in ink, he illustrates Bill Barrell, who in turn is represented by his piece from 1967, Summer Pleasures, painted after Thompson’s death. Barrell’s high-key colors and primitive forms clearly echo Thompson’s later work.

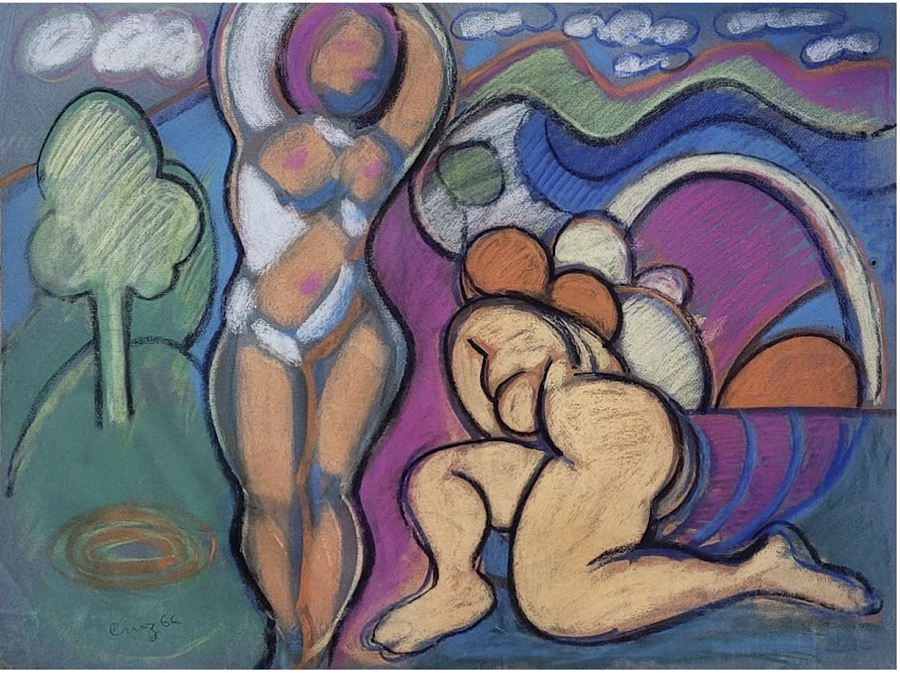

Emilio Cruz’s use of color and liberated nudes recalls Thompson’s art, but his approach to form is more stylized. Cruz — also a Black artist — studied at Seong Moy’s school and met Thompson there. The two were introduced by Gandy Brodie who, according to Cruz, influenced Thompson’s figurative paintings.

Brodie’s painting in the exhibition, A Matter of Life and Death, is a still life of flowers. Its use of washy oil paint echoes the loose, physical approach to painting evident in a collaborative image made by Bob Thompson and Bill Barrell.

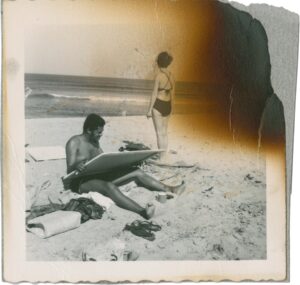

Painter Mimi Gross remembers meeting Thompson at a lumber yard in Provincetown when he was trying to “pick up” a friend of hers. “It was a summer that was so informal,” she says. “People met each other very casually and spent time together whether on the beach or eating or dancing. I had a house in the woods where people somehow all migrated to. We were all kind of a unit right away.”

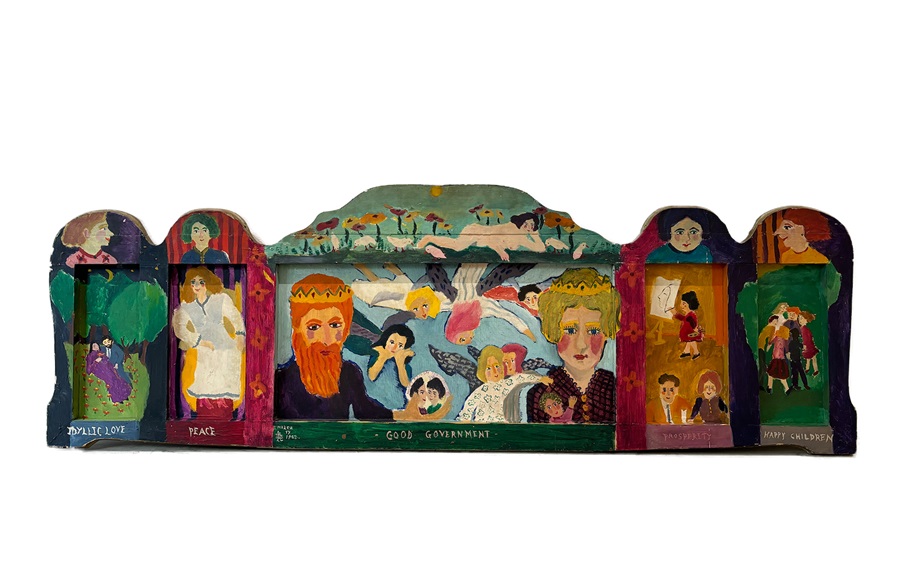

Gross was represented in the exhibition by a shaped panel, painted on both sides with folksy images of people and celestial beings. Like much of Thompson’s artwork, this is a riff on Western art history. Here she’s reinterpreting Italian painter Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Allegory of Good and Bad Government.

During a panel discussion organized by the gallery, Gross underscored the formative influence of her Provincetown peer group. She had grown up under the shadow of her father, sculptor Chaim Gross, and his circle of artist friends in Provincetown. “When I met Mary, Jay, and Bob, I suddenly met people of my own generation,” she said, of meeting Mary Frank, Jay Milder, and Bob Thompson. “I was encouraged to forge ahead instead of listening to those old guys, who weren’t necessarily encouraging, including my father.”

Provincetown also encouraged Thompson to forge his own direction. He returned to Louisville in the fall of 1958 but stayed for only a year. “He had been inspired by a stimulating summer in Provincetown,” wrote art historian Bridget R. Cooks in her essay “Dark Figures.” It was “where Thompson received serious interest and encouragement for his work for the first time.”

Thompson’s work was admired by his peers but also attracted the eyes of buyers, including Walter P. Chrysler Jr., a collector with a checkered reputation and deep pockets who bought 13 of his paintings.

“Bob now had a patron,” said Martha Henry, a private art dealer who helped produce the Harvey exhibition with the participation of Thompson’s family. “It encouraged him to drop out of college and move to New York a year later. He felt he had the support.”

Before moving to New York, Thompson had an exhibition in Louisville and continued to paint ambitiously, evidenced by a large-scale painting of a woman in an interior holding a rose. In 1959, he returned to Provincetown, where he participated in a three-person exhibition at Sun Gallery with Red Grooms and Jay Milder. That summer he also painted Beauty and the Beast, a work shown in 1960 at the Delancey Street Museum in New York and subsequently purchased by Reggie Cabral, the proprietor of Provincetown’s Atlantic House.

In New York, and then in Ibiza, Spain, where he lived with his wife before his death in Rome, Thompson’s networks extended outward, but his friends from Provincetown remained part of his life.

Those early years, spent among like-minded individuals, were essential to his artistic and personal development. Thompson and his friends often hung out at parties in his Conwell Street shack or at the dwellings on Tasha Hill where many artists stayed. “It was a rich place up there,” said Mary Frank in the panel discussion.

She remembers Thompson as a great dancer who had enough energy to run across the dunes while reciting Dylan Thomas poems.

“Whatever he did, he did full out, whether dancing, screwing, poetry, or painting,” she said. “There was a spine of intensity that ran through everything.”

The exhibition “I Am Myself: Early Works by Bob Thompson and Friends” will come to the Berta Walker Gallery in Provincetown in June.