EASTHAM — Sailors approaching Cape Cod’s ports in the 18th and 19th centuries would have seen the windmills first. They stood like sentinels over the bay, with an astonishing 67 of them lining the beaches of Provincetown and Truro alone, according to an 1836 map by James D. Graham.

The gusty shores of Cape Cod were ideal for windmills, especially because nearly every tree had been felled in the 17th century. In Provincetown and Truro, most windmills pumped water from the bay into large vats to dry into salt.

In addition to the saltworks, each town had two to five gristmills, town-owned windmills operated by a miller who turned grain into flour. A few towns, including Wellfleet, had a “tide mill” — a kind of water wheel powered by the changing tides.

Today there is only one windmill of any kind north of Jeremiah’s Gutter, the now-filled canal that once bisected the Cape near the Eastham-Orleans town line. That sole survivor is the gristmill in Eastham, which now stands across the highway from town hall, a testament to the Cape Cod of old.

Eastham’s windmill is unique on Cape Cod in that it is not a reconstruction. Its current parts are the same as when it last operated in the early 1900s, and it is still mechanically capable of grinding grain into coarse meal or fine flour.

A Building on the Move

Despite its age, Eastham’s windmill is probably a washashore. According to Alice Lowe, who wrote the 1968 volume Nauset on Cape Cod: A History of Eastham, the windmill was built in 1793 in Plymouth, then rafted across the bay to Truro. Lowe writes that the windmill was moved to Eastham in 1797. According to the Eastham Vacationist’s Handbook, published by the Eastham Chamber of Commerce in 1960, it took 22 oxen to move the structure.

There are other accounts of its origin, though.

Simeon L. Deyo’s History of Barnstable County, published in 1890, claims that the windmill was constructed in Provincetown in 1776 and moved to Eastham in 1795.

In Cape Cod: Its People and Their History, published in 1930, Henry Crocker Kittredge writes that the Eastham windmill was constructed in Eastham by a millwright named Thomas Paine — not to be confused with the Revolution-Era pamphleteer — in 1683 or 1684.

The Eastham Historical Society’s website offers a combination of the disparate histories: it says that the windmill was built in 1680 in Plymouth, moved to Truro in the 1770s, and arrived in Eastham in 1793.

The windmill was moved more than once, generally in concert with town hall. They initially stood together on a hill overlooking Salt Pond (then called Mill Pond); now they command opposite sides of Route 6 about half a mile to the south. Wherever the political center of Eastham was, the gristmill tended to follow.

Like the lighthouses of old, Eastham’s gristmill was inhabited: the miller and his family lived there, along with a pet cat to ward off mice. There is still a sign on Eastham’s windmill dedicated to Jason, a ship’s cat who lost his home in a wreck and spent the rest of his days protecting the mill.

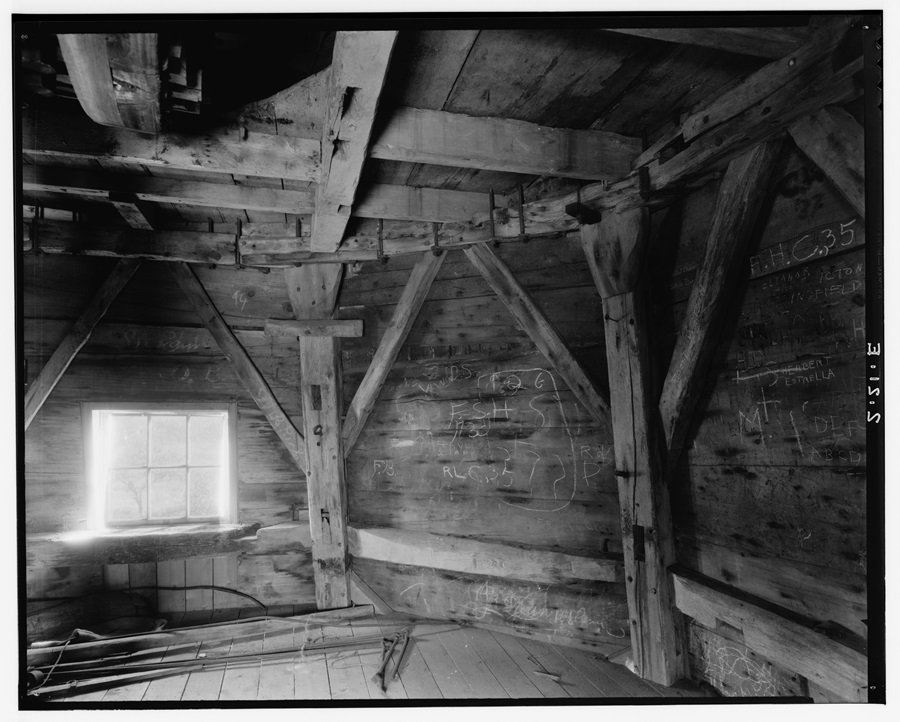

Inside the building, two slabs of granite weighing about 2,500 pounds each would grind against each other, causing the entire structure to rumble and shake. The bottom stone remained stationary while the windmill’s blades turned the top one at the speed of about one rotation per second. The space between the stones was minuscule, according to current miller Jerry Boucher: only about four-thousandths of an inch.

Eastham’s mill hasn’t been used to grind flour in decades, so Boucher’s title of “miller” is something of a formality. He works with the town’s recreation dept. to provide historical tours of the building.

The millstones had to be replaced every 30 years or so or else they could wear thin and crack, according to Boucher. The stone “doormat” at the current entrance to the windmill is one such cracked stone.

While the Eastham windmill’s current structure has only two floors, the original windmill had three: one at the bottom for storing grain, one in the middle where the grinding occurred, and another at the top for operating the gears that turned the millstones. Sometime in the 1800s, the first and second floors were combined into one — perhaps the miller had grown tired of carrying grain up ladders to load them into the hopper.

It was the advent of the railroad that put windmills out of business. Once Cape Cod residents could easily import grain from afar, fewer people needed to grow and grind it at home. Provincetown’s saltworks disappeared in the mid-1800s for the same reason, especially after large salt deposits were discovered in Syracuse, N.Y.

Provincetown and Truro’s salt-producing mills were dismantled soon after they shut down, the timbers finding new uses in other buildings. Many of the town-owned gristmills were sold off to private investors, including the Jonathan Young Windmill in Orleans.

Eastham’s windmill was also sold at least twice. According to the 1995 Eastham Historic Properties Survey, the women of the town’s Village Improvement Society raised money in 1895 to buy the mill and two adjoining lots from James E. Steele. They paid him $113.50 — the equivalent of about $4,250 today.

It is unclear when the windmill passed back into the town’s hands, but based on the Eastham Historical Properties Survey, it was probably sometime after 1928.

The six other windmills that remain on Cape Cod are also mostly town-owned again, but they are reconstructions of what used to be. Only Eastham’s windmill has its original millstones and other machinery — a relic of a time when the bay shore had enough windmills to make Don Quixote tremble in fright.