One December evening in 1971, a masked man knocked on the side door of Dr. Daniel H. Hiebert’s home in Provincetown.

“Turn around, I want to see your back,” the man said, according to a report in the Provincetown Advocate. At first, the 82-year-old doctor thought the man was joking. “What’s wrong with my back?” he asked. Then he saw the man’s knife. Hiebert, who was not easily intimidated, punched him in the face and shouted to his wife, Emily, to call the police. But the man had fled.

The Advocate reported that Hiebert thought the man might have been a “drug pusher.” He had recently been treating several young local fishermen for drug addiction, he said. They’d been spending excessive amounts on drugs. If the masked man was a dealer, perhaps he was angry and seeking revenge.

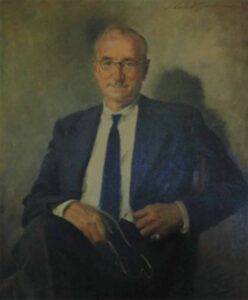

Daniel Hiebert, who was born in Hillsboro, Kans. in 1889, had been practicing medicine from his office at 322 Commercial St. for 52 years. He told the Advocate that he wasn’t afraid for his life and wouldn’t ask for police protection. The man would be “too scared to tangle with me again,” Hiebert said. The doctor had “big cornhusker hands,” the Advocate reported in Hiebert’s obituary the following year.

He was famous for making house calls at any hour and in any kind of weather in Provincetown and in Truro and Wellfleet, too. The Advocate obituary, published on July 27, 1972, said, “Whether it was the middle of the night or in the dead of winter, Dr. Hiebert never refused to visit a patient in need.”

Many of his patients were fishermen. In her Provincetown Magazine column, Jan Kelly described him “at 80 years old walking over planks from boat to boat to get to an injured fisherman. Bag in hand, wind whipping the boards, bouncing off reflecting waves and swaying hulls with his beige overcoat in trenchcoat style with a fur collar dampening in the driven east wind, he was just doing a boat call.”

Hiebert’s father was a farmer and Mennonite minister. His mother died after giving birth to twins when he was two years old. When he was 11, he moved in with his oldest stepbrother, John Hiebert. The four nephews with whom Heibert grew up all became medical professionals. “At one American Medical Association convention,” reported the Advocate, “there were 24 Dr. Hieberts in attendance.”

Hiebert went to medical school at Boston University, where he was president of his class all four years and graduated in 1918. In 1919, he married Emily, with whom he had one daughter, Ruth.

In that same year, he moved to Provincetown and established his practice. He did his own X-rays, set broken bones, sewed cuts, diagnosed unusual ailments, and responded to emergencies before there was a town rescue squad. He delivered some 1,500 babies, including all the children in the family of Provincetown’s Mel Joseph.

Joseph, who was born in 1951 on West Vine Street, broke his nose in 1968 diving off MacMillan Pier into shallow water. He walked into Hiebert’s office, and the doctor stuck a tongue depressor up one of Joseph’s nostrils and braced a large finger against his nose. Then he snapped it back into place.

“Pain went up my forehead,” says Joseph, “down my back, and came out my ass like a fire.”

“You’ll be fine now, son,” Hiebert told Joseph in his gravelly voice. He had “no bedside manner at all,” says Joseph, “but a great smile.”

Joseph adds that he didn’t pay anything for the impromptu nose job. “Back then, paperwork and all that was kind of irrelevant,” he says. “No insurance. No parental permission.”

Indeed, many people never paid a cent for Hiebert’s services. Emily would write down the charges in a ledger — “every nickel, every dime,” says Joseph. But the doctor wouldn’t let her send the bill. “He was going to take care of you no matter what,” Joseph says. “And the town took care of him.”

Those “cornhusker hands” were celebrated for what Mary Heaton Vorse called “Dr. Dan’s embroidery work” — his stitching. “He could stitch up cuts and wounds in such a careful and methodical way that most injuries would heal scarless,” wrote Kelly.

One of those wounds was on the back of the head of Norman Mailer, who claimed that he was clubbed by a Provincetown cop in June 1960 on his way home from a night of barhopping with his wife, Adele. The writer was arrested for being drunk and disorderly and hauled off to jail, and Hiebert was called to tend to him. Mailer’s trial in District Court was reported by Dwight Macdonald in the New Yorker that October.

“When Dr. Daniel Hiebert, summoned from his bed, had wanted to shave the defendant’s head,” Macdonald wrote, “the latter had indignantly refused to let him, saying he was going to a dance the next night; he had made many loud and uncomplimentary remarks to the Doctor (though he had finally let him bandage his head). ‘Why don’t you sober up?’ Dr. Hiebert had said as he left.”

By all accounts, Dr. Hiebert was chronically exhausted. He would drive to the houses of his patients, park his car, and promptly fall asleep. In later years, he hired a driver. “He’d fall asleep taking your pulse,” says Joseph, “and you’d be sitting there not knowing if you should shake him.”

Betty White, who was born in Provincetown and now lives in Truro, split her head open when she was nine. Her family went to Thomas F. Perry, the other doctor in town, who practiced from 1955 through the ’70s from his house at 140 Bradford St. His services weren’t free, though. “He expected to make a living,” says Joseph.

White was driven directly to Hiebert’s office, and he got to work sewing up her head — until he dozed off mid-stitch.

“My mother kept having to wake him up — ‘Doctor, Doctor, please wake up,’ ” recalls White. Emily kept poking her head into the room. “Probably checking to see if he was still awake,” says White. In the end, she says, “Dr. Hiebert sewed my head quite nicely.”

The late Beata Cook told a similar story to Kaimi Rose Lum in a 2019 profile in the Independent. “One night, late,” said Cook, “my grandmother began feeling very unwell, with an uncomfortable feeling in her chest and some dizziness. So she called Dr. Hiebert. He arrived shortly afterwards, removed his Stetson hat, and plunked down beside her on the couch. He asked her a few questions, then foregoing the use of his stethoscope, he rested his head on her ample bosom to listen to her heartbeat and promptly fell asleep. Nanny allowed him to rest in this position for about 10 minutes, then she gently poked Dr. Hiebert and said, ‘Dr. Hiebert, you have to get off my titties and go home now.’ All was well. He got a much-needed nap, and she got through the night just fine.”

Kelly wrote that in 1960 Hiebert said, “50 years from now there will no longer be any general practitioner. Every physician will be specializing. Whatever the advantages, the old human relationship between a patient and the family doctor will be lost and that’s something invaluable in the art of healing.”

“Everybody dies famous in a small town,” says Joseph, paraphrasing Miranda Lambert. Dr. Hiebert died at 83 at Cape Cod Hospital on July 24, 1972. He’s buried in the Provincetown Cemetery, where he and Emily, who died in 1985, share a gravestone inscribed with a caduceus.

Several hundred people attended his funeral, filling every seat in the Methodist Church and overflowing outside the building, reported the Advocate. Busy until the last, Dr. Hiebert had been “stricken while making a house call.”