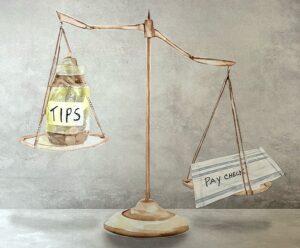

It makes sense that a ballot measure that would more than double the wages that must be paid to tipped employees would be popular with at least one large block of Outer Cape voters: tipped employees. But that does not appear to be the case.

Question 5, if it passes, would raise the wage that employers must pay many hotel, bar, and restaurant workers from the current $6.75 per hour to the state’s full minimum wage, currently $15 an hour, over the next five years. The first increase of $3.15 per hour would take effect on Jan. 1, and a series of smaller increases over the next four years would lead to the end of a separate “tipped minimum wage” in January 2029.

A second provision would at the same time change the state’s laws on employer-mandated “tip pools” — arrangements that formally spread tips across a group of workers.

Under current law, tips can be pooled only with other “wait staff employees” such as bussers, food runners, and restaurant hosts. Question 5 would allow tips to be distributed to any employee who is not an owner or manager once the owner stops using the “tipped minimum wage” and pays all workers at least $15 per hour.

Four restaurant servers who spoke with the Independent said they worried that distributing tips among all employees would erase any gains from the increased minimum wage.

“I’ve worked in restaurants for 20 years, including in California where restaurants have to pay a higher minimum wage to servers, and it was wonderful,” said Ben Kramer, who has most recently worked at Strangers & Saints, Café Heaven, and the Nor’east Beer Garden in Provincetown. “The extra money paid the taxes on my tip income, and there was usually some left over to help with bills.”

But adding chefs, prep cooks, and dishwashers to the tipping pool would dilute Question 5’s wage increase, Kramer said. “The people I’ve talked to are having a bit of a freak-out because increasing the wage by $10 is not enough to make up for splitting a tip pool with 10 more people,” he said.

Matthew Hines has worked as a server and bartender in Ohio, California, and at the Crown & Anchor in Provincetown. He changed his mind on Question 5 because of the tip-pool provision.

“I remember when California increased wages for servers — it felt like I could finally catch my breath and stop counting my groceries,” said Hines.

“After about two years, management started cutting wages for dishwashers and cooks and paying them out of our tips, pushing us back into poverty,” Hines said. “Kitchen employees had always been paid salaries, and owners found a way to pay them with other workers’ money instead.”

Joe MacDougall has worked as a server since 1988 in Boston, New York City, and at Local 186 and Mac’s Seafood in Provincetown. He voted for Question 5 during early voting in Eastham, but he told the Independent he’s worried about what could come next.

“Tipping culture didn’t change when they raised the minimum wage in New York City,” MacDougall said. “And if kitchen staff receive a share of the tips and it means an additional bump in their take-home pay, I’m for that.

“The fear I have is that a dishwasher who used to get $25 an hour will now get $22 because they get a share of tips,” MacDougall said. “I think including the tip pool in this ballot question might have been an error, because even though I support the concept, I’m worried the implementation will make me regret my vote.”

Question 5 was sponsored by One Fair Wage, a national nonprofit that has put similar measures on this year’s ballot in Michigan, Ohio, and Arizona. A page on the One Fair Wage Coalition’s website says that allowing tips to be pooled across all nonmanagement employees would “increase teamwork within all restaurant staff and lift up all workers.”

“Allowing restaurants and bars the option to share tips with back-of-house workers would increase racial and occupational equity,” the group’s fact sheet says.

Although the Mass. Restaurant Association, which represents owners, has long argued that increasing wages for tipped employees would increase costs paid by diners and eventually lower the take-home pay of servers, research done by two UMass Amherst professors suggests otherwise.

Economist Jeannette Wicks-Lim and sociologist Jasmine Kerressey analyzed the take-home pay of tipped employees in hotels and restaurants in several states, including the seven that currently require tipped employees to be paid the full minimum wage: California, Oregon, Washington, Nevada, Montana, Minnesota, and Alaska. The researchers found that tipped workers in states that do not allow restaurants to pay workers less than minimum wage earn more in wages and tips than tipped workers in states with subminimum wages.

Their paper did not directly address tip pooling, and Wicks-Lim told the Independent that she’s “not aware of any studies that have looked systematically at the impact of tip pooling on tipped workers’ earnings.”

The seven states that require full minimum wages have different rules regarding tip pools, and Wicks-Lim said that after a preliminary look at earnings data in those states, “As far as I can tell, there is no pattern between whether there are no tip pools, traditional tip pools, or nontraditional tip pools” that can include all nonmanagement employees.

Wicks-Lim and Kerressey also found that the effects of increased wages on menu prices in restaurants are likely to be small. The overall cost increase would come to about 2 percent of restaurants’ sales revenue, they wrote, “equal to a $50 restaurant meal increasing to $51.”

Nina West lives in Wellfleet and has worked as a server and bartender for more than 40 years, mostly in New York City and at Enzo’s, the Gifford House, and the Crown & Anchor in Provincetown.

“I believe that kitchen staff deserve to be paid better, and I’d love to get an actual minimum wage myself,” West said. “But I can predict how this is going to play out. Management having complete control over the tip pool is a deal breaker for me.”