The results are in from the annual seine in the Chesapeake Bay to determine the status of the juvenile striped bass population, and the news isn’t good.

Samples of fish are collected in 100-foot mesh seines set by hand in 22 stations in three rounds in July, August, and September on Maryland’s portion of the bay. The survey documents not only the so-called young-of-the-year striped bass but also the relative abundance of other fish. Over 100 species have been collected in these surveys since they began in 1954, according to the Maryland Dept. of Natural Resources, which conducts them.

East Coast anglers know why those of us on Cape Cod care about what happens in Maryland: Chesapeake Bay spawning and nursery areas, like the Potomac, Choptank, and James rivers and Susquehanna Flats, produce the majority of the entire coast’s migratory striped bass.

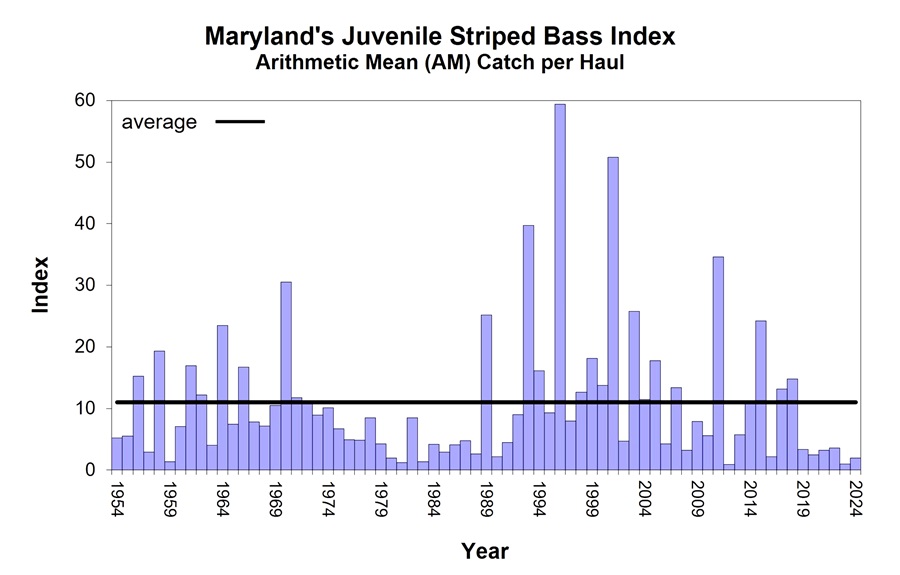

The 2024 survey recorded 2.0 juvenile striped bass per seine haul, a minor increase from last year, but that count was the second lowest since 1957, according to the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. The number is also far below the long-term average of 11.3.

Additionally, Virginia’s 2024 juvenile bass counts recorded 3.43 young stripers per haul, which is also far below that state’s long-term average of 7.77. These seine numbers indicate that low reproduction is a broad issue affecting the whole Chesapeake Bay. It’s especially daunting that the bay has now experienced six consecutive years of striped bass spawning failure.

Many marine science experts consider these annual surveys to be crucial indicators of future population trends. These findings suggest there could be difficult years ahead for both the commercial and recreational fisheries and even legitimate concerns about the future of striped bass along the entire Northeast coast. After all, fewer young fish generally mean fewer adult fish in the future.

The surveys reveal that the decline in striped bass populations is not just a matter of overfishing.

Recent research reveals other serious issues affecting bass populations, including mycobacteriosis, a fatal disease; an influx of invasive blue catfish into the spawning river areas; pollution from the ground and subsequent habitat loss; and the peripheral effects of climate change, which not only mean increasingly warming seas but also ocean acidification.

When it comes to the poor spawning results, the Maryland survey report emphasizes that last issue: “warm conditions in winter continue to negatively impact the reproductive success of striped bass, whose larvae are very sensitive to water conditions and food availability in the first several weeks after hatching. Other species with similar spawning behavior such as white perch, yellow perch, and American shad also experienced below-average reproduction this year.”

For the marine biologists who study the species, the decline in striped bass population points to an ecosystem under increasing strain. These are trends that have deep and broad effects; they jeopardize the fish and the fishermen who catch them for a living and the communities that rely on that balance.

We have a few months to wait before NOAA and Marine Fisheries decide if any modifications to the existing rule will be forthcoming. I am not feeling hopeful.