It bounds down the alleyways off Commercial Street, its black cloak trailing in the wind, dark laughter bubbling from behind its horrible metal mask. Children dash home in terror the moment the sky goes dark; townspeople scream when the towering phantom lunges at them, its glowing eyes drilling into their souls. The Black Flash has returned just in time for Halloween.

It’s October 1939, and winter has come early to Cape Cod. Seagulls wheel in droves over the frigid bay — so many that Charles Moller, a Provincetown hunter, starts a campaign to kill and cook them in preparation for the hungry months ahead. Local police are on the trail of a serial arsonist targeting empty vacation homes on Miller Hill Road. Most of the locals, however, couldn’t care less about fires and birds: they have a phantom on their hands.

The earliest mention of the Black Flash (also called “the Blot”) dates to the Oct. 24, 1939 issue of the Boston Globe, which describes a seven-foot-tall apparition in a black cloak jumping over fences and chasing children through the streets of Provincetown.

“Stories of the Flash have circulated here almost every Fall for the past eight years,” the Globe reported. “About four years ago it was blamed for setting a string of fires which resulted in more than $250,000 worth of damage to property.”

Two days after the Globe article, the Provincetown Advocate printed a front-page story about local encounters with the phantom. “We’ve had the Black Flash here every fourth year ever since I was man and boy,” Phineus Blackstrap, a sea captain, told the Advocate. “I never seen him without he’s gnawing away at a skully-jo” (salted cod or haddock jerky once popular among Provincetown fishermen).

Blackstrap claimed to have met the Flash on the road to Helltown, a fishing village once frequented by pirates and gamblers that existed somewhere near Clapps Pond and Hatches Harbor.

Officially, the Provincetown police didn’t recognize the existence of the Black Flash. Chief Tony Tarvers was more concerned with finding the mystery arsonist — but as reports began to surface that the Black Flash could spew flames from its mouth, he must have wondered if there was a connection.

On Oct. 26, Tarvers and State Fire Inspector John N. Sullivan questioned three local youths about the arsons. Provincetown boys were notoriously belligerent, especially on their way to and from the newly established community center at the Eastern School House (now the Schoolhouse Gallery).

The three youths were never officially named, but it is likely that they were the same three the police suspected of being the Black Flash: one, a boy named Ford, was a hurdler on the track team; another, nicknamed Stretch, was the only one tall enough to resemble the reports. A young man named Rego, who had recently been refused an off-season job on the police force, was the third suspect.

The boys said they knew nothing.

With Halloween fast approaching and no leads in sight, Tarvers decided to sponsor a party at the community center to provide alternative entertainment for potential troublemakers. The gathering, which featured doughnut bobbing, an obstacle course, and a showing of the 1922 adventure movie Captain Fly-by-Night, attracted about a thousand people — 400 children and 600 adults, according to the Advocate.

One of those children, three-year-old Manuel Jason Jr., came dressed as the Black Flash and won a dollar for his costume. “As far as I am concerned, the Black Flash is dead and gone,” Tarvers proudly declared after the festivities.

The following Jan. 31, Tarvers captured the serial arsonist, 40-year-old Joseph “Happy” Viera, who was spotted breaking into a cottage on Bradford Street. With the arsonist behind bars, Tarvers must have thought the worst of the trouble was behind him. It seemed as if the citizens of Provincetown could breathe a sigh of relief.

It was not to be.

The Black Flash, relentless as ever, continued to haunt the town until 1945, even after most of Tarvers’s suspects had left to fight in World War II. According to Massachusetts folklorist Robert Ellis Cahill, four policemen, including Francis Marshall, cornered the Black Flash at the Bradford School (now Provincetown Commons) in November 1945, only to have him escape, laughing manically, over the schoolyard’s 10-foot-high fence.

Officer Marshall said the Flash was “tall, but not as tall as most of his victims had described him.” Its “mask” was supposedly an old flour-sifter — which would explain the “long silver ears” one eyewitness, farmer Charlie Farley, had reported.

The most detailed account of an encounter with the Black Flash comes from Provincetown resident Allen Janard, who told Cahill he saw the phantom twice in 1945, both times prowling by his house at 34 Standish St. “It was enormous,” Cahill wrote. “Its face was so evil-looking that Allen had to turn his own face away, and its horrid laugh, more like a deep gurgle, penetrated his eardrums.”

Thirteen-year-old Janard armed himself with a carving knife during the second encounter, when he saw the thing crawling out of the dunes toward his family home. “All I could hear was my heartbeat,” he said, recalling the seemingly endless moments as the monster lurked at the back door. Janard’s brother Louie, also home at the time, was the one who managed to drive the Black Flash away — by dumping a bucket of scalding water on it from an attic window.

“They saw him retreat through the back yard, a dripping black phantom, shivering from head to toe, not looking half as fearsome as he had when he arrived,” Cahill wrote.

Reports of the Black Flash dwindled after 1945, but its identity remained a mystery. Marshall claimed to know the perpetrator’s identity — “He was four men,” he said, “who sometimes played the part alone, and sometimes together” — but refused to reveal their names. Marshall died in 1995, taking the secret with him.

The Black Flash was a staple of local culture 80 years ago. There was at least one copycat, too: around the same time, Wellfleet residents were tormented by a strange howling at Paine Hollow. Farmers combed the area, armed with shotguns to drive away their mysterious “Tarzan,” but found nobody.

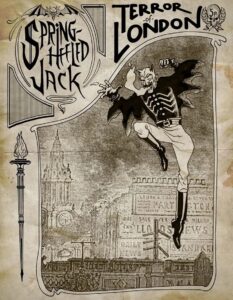

While the Black Flash’s identity seems doomed to remain a mystery, it is far from the only tale of a fire-breathing phantom who terrifies an unsuspecting community. The most famous, London’s Spring-Heeled Jack, is theorized by some historians to have been an alter ego for the 19th century’s “Mad Marquis,” Henry de la Poer Beresford.

While the Outer Cape is rarely thought of as a stomping ground for insane noblemen, it has always been a haven for eccentric characters: indeed, if the Black Flash ever decides to return to its favorite haunt, it may well find itself comfortably at home.