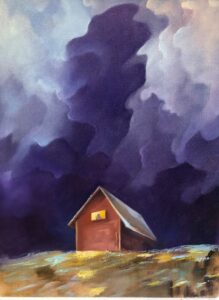

It’s never a clear day in a Bowersock painting. His clouds — rising over sparkling water or looming over farmland — suggest narratives, but ethereal ones. “My skies aren’t real,” the artist says. “They’re metaphors.”

Artist and gallerist Steve Bowersock sits on a stool in his second-floor studio behind Yardarm Liquors on Old Anne Page Way in Provincetown, surrounded by paintings at different stages of completion. He’s in no rush to finish them. Or even to start them, it seems.

He walks to the back of the studio to pull out two wood panels he’s been working on. He’s spent a week on sketches for each. “Planning ahead is key,” he says. “It sets the next stage of your painting. If you have a bad composition, the painting’s going to fall apart.”

When he’s working on wood panels, he sands them down and adds multiple layers of gesso on top. He likes a smooth surface, which allows his paint to glide. He can spend hours blocking in colors in “layers and layers and layers of thin washes of paint,” he says.

The prepped panels in his studio show incredibly detailed underpaintings. He uses raw umber, burnt umber, or any earth tone, he says, for the underpaintings. “This is the old technique of warming up your paints — it tones the canvas down.”

Colors and shapes then rise from those backgrounds, often in brushstrokes that feel so light that the paintings take on the translucence of watercolors.

In one, A Needed Escape, a deep wine-colored cloud rises in a purple sky, waves sparkle below, and the sun lights up the edges. The landscape seems familiar — an Outer Cape pond, maybe. Or in Don’t Let Me Fade Away, the viewer is positioned on a marsh; beyond yellow beach grasses are the faintest whitecaps on the bay. But in All That Matters Is Where You Lay Your Head, four houses are set on a flat landscape of dark, plowed earth, one of them catching a stream of light-filled haze. The home he left behind as a young man, maybe. He paints from his imagination, but his skies reference both Cape Cod and the rural Midwest, he says. He grew up in Bloomington, Ohio.

“I was a kid on the farm trying to escape to somewhere. It took me 25 years,” he says. Part of that need to escape had to do with the fact that “gay doesn’t exist where I’m from,” he says, only half joking. And part of it is that making art as a way to make a living wasn’t an option there. When he goes home, he says, he still gets questions like, “How’s your hobby going?”

Growing up, Bowersock knew he wanted to be an artist. But it was a calling he resisted for a long time. “I was always painting and drawing as a kid, it was my escape, pretty much until I joined the Marines in 1990,” he says. “I joined the military because that’s what masculine men did.” He got a job at an aluminum plant in Ohio after the Marines. He moved to New Hampshire with his then-wife and took a farm job. Neither the job nor the marriage lasted.

Bowersock opened his eponymous gallery with his partner, the late Michael Senger, on Commercial Street 20 years ago. Still, a visitor can imagine him in his farm country hometown. He wears a flannel shirt with a purple undershirt; a streak of green oil paint runs down the right leg of his frayed jeans. He wipes his paintbrush on a pale blue cloth. He has a trim white beard and glasses.

The practice of painting allows him to get out of his head, where the persistent voice of self-criticism resides, Bowersock says.

His compositions are as much explorations or questions as they are narratives — for himself and for the viewer. “I create the story, and now the viewer can see what they want to see in it,” he says. “One painting can have multiple meanings.”

Even after his sketches and layers, “I don’t know what it’s going to be yet,” he says, dabbing a brush on mixed turquoise oil paint as he talks. He lets color lead him. “You throw red in. Is it love, hate, anger? What is it?”

Bowersock painted a series of storms moving over the breakwater when he was in what he calls his “red balloon phase.” In one of the paintings, a red balloon disappears beyond the breakwater. “Here,” he points to the painting, “I’ve lost my balloon — where do I go with the rest of my life?”