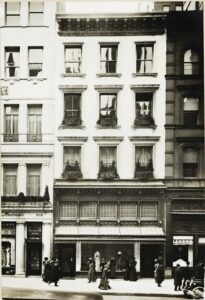

Henri Bendel, the store, was synonymous in the American imagination with good taste, astronomical price tags, and a certain uptown vision of the good life. To shop at Henri Bendel was to enter a sanctum of style and partake in a sacred ritual — shopping! — that dates back to the Gilded Age when, in 1895, the store first opened its doors in New York’s Greenwich Village.

The Vanderbilts bought Chanel there, and it became every society lady for herself during the store’s warehouse sale, when aristocracy was reduced to anarchy by means of feathery hats and silk scarves. Almost a century later, the store would become aspirational to American youth, who watched the trust fund teens of Gossip Girl casually purchase five-figure debutante gowns. Henri Bendel, the store, was a mirage for just how well the well-to-do lived. (The company was dissolved in 2019, and all 23 of its stores closed.)

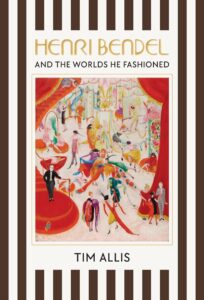

But what about the man behind the eponymous store? “Remarkably little is known about him,” says Tim Allis, a former senior editor at InStyle and the author of Henri Bendel and the Worlds He Fashioned, the first biography of the American businessman and tastemaker. The book is being brought out this month by the University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press.

Allis says the biography almost did not come to be: Bendel left no memoir, diaries, or even letters. He was as elusive as his store was illustrious. But Allis, who comes from Lafayette, the same southern Louisiana city as Bendel, was determined to discover how a man from humble roots could become a symbol for wealth itself.

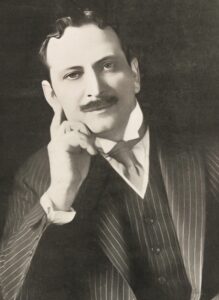

Between the public record — in particular, Bendel’s syndicated column, in which he lavished praise on some fashion trends and dismissed others with droll wit (which Allis’s book quotes to great effect) — and interviews Allis conducted with Bendel’s descendants, a picture of Bendel emerges: “that of a man of tremendous creativity, with a tireless work ethic and a passion for beauty and art in myriad forms,” Allis writes.

Also, a picture of a closeted gay man who was utterly discreet about his “unusual domestic arrangements,” as Allis puts it. “I’m worried I outed Henri,” Allis says. Even though Bendel’s sexuality was an open secret among his friends and family, it is all but invisible in the official records. “I hope he’ll forgive this intrusion upon that privacy,” Allis writes in an afterword, “which might now be appreciated as an act of overdue liberation.”

Henri Bendel and the Worlds He Fashioned is a thorough yet breezy read, full of archival images and documents from the 20th century: sketches of Molyneaux dresses, images of Bendel’s shop on Fifth Avenue, original Bendel hatboxes, photos of Bendel’s mansion on Long Island. The book is itself a beautiful object, which is good because Bendel wouldn’t have had it any other way.

Bendel was born in 1868 to Jewish immigrants in Vermilionville, La., now called Lafayette. “Bendel’s particular nook of Louisiana, a sticky-sweet lowland of barely moving bayous and sprawling live oak trees, not to mention mosquitoes, snakes, and stifling summer heat, was a fairly unique place to grow up,” Allis writes. Bendel’s family ran a general merchandise store on the first floor of their two-story home, and it was here that the young Henri first learned about business.

Bendel was teased as a child for playing with paper dolls, as Allis learned from Elisabeth Denbo Montgomery, a Bendel family friend. Where his peers saw femininity, Bendel’s parents saw talent. He was sent to a local private school and, by the time he was 12, Bendel was enrolled in college at a Jesuit boys’ school. “His Jesuit education is really important to his later career, I think,” says Allis. “He was learning Latin and about antiquity and art. And the Jesuits had him decorating the altar.

“But here’s the special sauce,” Allis confides. “He spoke French growing up in Louisiana — in the house he grew up in and the community around him. Speaking French was his turnkey. It allowed him to go to France as a buyer and crack the French couture houses, which were incredibly snobbish and elitist and not eager to let tawdry Americans in.” By the time his store was up and running, Bendel was traveling to Paris at least twice a year on buying trips.

Allis’s biography thus reveals that what at first look like contradictions — how does one go from small-town Louisiana to French couture houses? — actually make perfect sense. It’s not in spite of Bendel’s Louisiana upbringing that he became the Henri Bendel; it’s because of it.

Bendel was, in fact, enamored of Louisiana, and even as he became more and more a citizen of New York, he never forgot his birthplace and championed it as a future bastion of finance, art, and culture. Bendel expressed confusion as to why Northerners traveled for vacation to Florida instead of Louisiana.

“I have found Palm Beach a sort of artificiality, an unnatural, high pitched vein of life,” he said. “Now consider Louisiana, with her settings of beauty, the charm of her people and the many other things she has to offer. In Florida you have to buy flowers from hothouses. Here, you find the real thing.”

Bendel was prone to such pronouncements. “Above all, the American mentality is not creative,” he said, comparing the way American women and French women dress. “Americans adapt and modify and shape better than anyone else in the world…. But adapting and suiting, ah, that is not creation!”

Allis wonders if he would have liked Bendel. “He reputedly had a great sense of humor, was gracious and charming,” he writes. “He could also be a prig, a fussbudget, and high-hatted. Particular, in the pejorative sense (well, I fear I’ve been accused of that).”

The connection between the two is deep, though: Allis grew up on land that had once been Bendel’s property. “Back then Bendel Garden was just the name of our subdivision, adjacent to Bendel Road,” he says. “It was only in my 20s that I finally made the connection.”

Like Bendel, Allis grew up gay in Lafayette and felt ambivalent about his surroundings. On the one hand, there was all the typical Louisiana stuff: “Fishing? No, thank you. Hunting? No. Football? No, thank you,” Allis says. On the other hand, “Lafayette is a truly friendly, spirited place. Straight guys at the gym talk about cooking as much as sports. It’s known for Cajun food and music and Mardi Gras. I remember that when I’d come home for Christmas in the early 1980s my best friend and I would hit the gay bars and we had — no kidding — nine to choose from.”

Allis is adept at nuance, holding one truth in each hand and then using his fingers to braid them together. In Henri Bendel and the Worlds He Fashioned, this skill is on display as Allis takes the apparent contradictions that form Bendel’s biography and lines them up like clothes on a rack.