Lee McColgan and A House Restored

The first thing Lee McColgan wants you to know is that preserving an 18th-century New England house is not like an episode of HGTV’s Fixer Upper. There’s no big final reveal after the last commercial break.

“It’s endless,” he says of the preservation process, which is constantly evolving. For him, it also requires the use of authentic period techniques.

McColgan, author of A House Restored: The Tragedies and Triumphs of Saving a New England Colonial, will describe repairing the Loring House in Pembroke at the Wellfleet Public Library, 55 West Main St., on Tuesday, June 11 at 7 p.m. The event is part of the Wellfleet Historical Society speaker series and follows a recent New York Times feature.

Before restoring the house, which was built in 1702, McColgan did what many yearn to do but don’t: he quit his corporate job in finance and followed a passion for woodworking. He says his supportive spouse, Elizabeth Bailey, and “low overhead” — i.e., no children — allowed him to do it.

After encountering significant structural issues, McColgan knew he needed help. He apprenticed with a timber framer, worked alongside a window specialist at Boston’s Old North Church and Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House in Concord, and learned how to work with the building materials used in the 18th century. One of the trickiest was plaster.

“What they used to do was take limestone or seashells and heat it until it broke down into a powder that could turn into a putty when water was added,” he says. “Lime plaster is not something you can just go down to the hardware store and buy.”

While few early 18th-century homes remain on the Outer Cape, McColgan says many of the lessons he learned apply to structures built in the 19th century, which are more common here. He doesn’t urge everyone to use centuries-old methods, but he notes that newer is not always better.

“Building technology is driven by ways to do things cheaper,” he says. “If you’re considering something like a building’s longevity, a big eight-by-eight oak-framed structure is going to be far more durable than new growth pine nailed together.”

The talk is free. See wellfleethistoricalsociety.org for more information. —Katy Abel

Oh, the Mysteries of Bohemia

In the early 20th century, artists, writers, and intellectuals flocked to Provincetown, dedicated to reform and a new way of being. These bohemians, as they were known, laid the foundation for the creative experimentation that continues to this day.

“Beyond Bohemia” is a celebration of this legacy with art, music, lectures, book signings, and plein air gatherings at the Wellfleet Public Library, 55 West Main St., through June 28.

It features artists Paul Schulenburg, Dottie Leatherwood, Marc Hanson, Karri Allrich, Maryalice Eizenberg, Jonathan McPhillips, Andrea Petitto, and Marc Kundmann.

Kundmann moved with his partner to the Outer Cape from Minneapolis in 1997 and took painting classes with the artist Jim Peters soon after. “I had never experienced a place where we could totally be ourselves until we moved here,” he says.

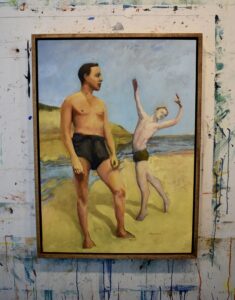

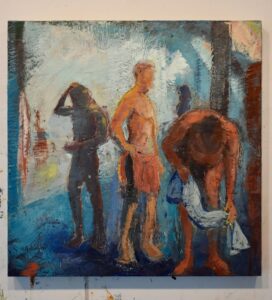

Now, Kundmann works in oil and encaustic, mainly in a studio on Bradford Street in Provincetown’s West End. Often he carves into his work with a palette knife to create depth. The texture of encaustic gives weight and a sculptural quality to his figurative works.

Four of his paintings are on display at the library, and they draw inspiration from bohemian figures of the time. Kundmann says his oil and wax painting Baths was inspired by the artists Marsden Hartley and Charles Demuth. Intermission, he says, is based on a “little snippet” from Warren Beatty’s 1981 film Reds, which is partly set on the Outer Cape. It follows the journalists John Reed and Louise Bryant and their friends, including Eugene O’Neill.

“I was interested in Louise Bryant — as a woman, she really fought to be a recognized journalist,” he says. He adds that John Taylor Williams’s 2022 book The Shores of Bohemia helped him develop the imagined historical portrait of Bryant in Intermission.

“Bohemian artists moved here to find their voice,” says Kundmann. “They came for the same reason I came.”

See addisonart.com for a full schedule of “Beyond Bohemia” events. —Pat Kearns

John Frank’s Experiments With Form

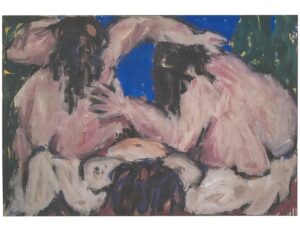

Like his contemporaries Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline, Philip Guston, and others oscillating between Provincetown and New York in the mid-20th century, the painter and Kentucky native John Frank flattened out and abstracted shapes and patterns in his work. He was not an abstract expressionist but a figurative expressionist.

“It was a time when abstraction was very popular, and there was a small group of artists who came out of that into expressionist figuration,” says Robert Henry, who curated a retrospective Frank exhibition that opens with a reception at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum on Friday, June 7 at 6 p.m.

Frank’s experimentation with form expanded beyond the material. His year in a Zen monastery in Kyoto, Japan following service in the Korean War sparked a lifelong interest in the art and traditions of Buddhist culture, which he deepened with regular visits to India, Tibet, and Nepal. For Frank, these experiences not only created an understanding of art as a bridge within and between people but also expanded his understanding and use of line, texture, and color.

Frank, who died in 2018, had deep ties to Provincetown as both an artist and teacher, from his early work as Motherwell’s studio assistant to supporting young artists at PAAM. Most of the paintings featured in the exhibition are on loan from the John Frank Estate and Frank’s widow, Kathi Robinson Frank, but Henry says at least one will be added to PAAM’s permanent collection. He adds that visitors should look in Frank’s work for “the expressiveness of the gestures of the figures and the relationship of the figures to one another.”

The exhibition is on view until July 21. For tickets and more information, see paam.org. —Katy

Josh Cox at PIFF

“I had this image in my mind’s eye of two boys standing with their backs to each other at a distance,” says Josh Cox about the inspiration for his short film Far From Water. “I wondered what could have caused a divide between these two people. That was my starting point, and I wrote the rest of the script around that image.”

Far From Water will premiere at the Provincetown International Film Festival on Wednesday, June 12 at 7:30 p.m. at Waters Edge Cinema (237 Commercial St.).

Cox was born and reared in Sandwich and graduated from Sturgis Charter School in Hyannis in 2016. He now lives in New York City.

Cox shot Far From Water at Great Island in Wellfleet. “There was something special about the trail,” he says. “There was so much beautiful tall grass. And the weather was super moody when we filmed.”

The short, which Cox wrote and filmed last summer, follows two friends who, after a moment of intimacy, begin to question the status and future of their relationship.

“Normally my work is about strangers meeting for the first time,” says Cox, who’s made five short films. “It was challenging to make something from a more established, complex point of view.”

The film stars Jarid Dominguez and Lucas Nealon as the two unnamed friends. “I just reached out to each of them on Instagram to see if they were into it,” Cox says. It was like a digital version of street casting, he says.

Cox says he drew inspiration from Andrea Arnold’s 2016 film American Honey. Arnold is a guerilla filmmaker, shooting quickly and without contrivance. “You get out there and, if something interesting happens, you capture that,” says Cox. “It might be what the actors are doing, but it might be what’s happening in nature. Keeping some parts unscripted makes the film more authentic.”

“This is my first time attending the film festival,” the 25-year-old says. “I have a home base on Cape Cod, which is why I love making films here. Plus, there’s not too many places that will beat the Cape for beautiful landscapes.” —Paul Sullivan

Love Triangle

A funhouse mirror — and its liquid manipulation of figure and form — dissolves the viewer’s signposts of age, gender, and convention. So does Sarah Blakley-Cartwright’s 2023 novel Alice Sadie Celine.

The novel traces the triangle of relationships among three women: Alice, a burgeoning actor; Sadie, a person seeking her sense of self; and Celine, a celebrated feminist and professor at UC Berkeley. Celine is Sadie’s mother. Sadie is Alice’s best friend. Alice is Celine’s secret lover.

“Celine came to me first,” says Blakley-Cartwright. “Then I started wondering who would be that person’s daughter — and who would be the best friend caught between these very strong pillars.”

Blakley-Cartwright will read from the novel and host a Q&A at the Wellfleet Public Library, 55 West Main St., on Friday, June 7 at 6 p.m.

The question of what it is for women to live and love for themselves ricochets between Alice, Sadie, and Celine. Their engagement with each other presents a way to think about the external gendered expectations projected onto women and, in some cases, reinforced by women who judge each other and themselves.

Blakley-Cartwright was curious to experiment with the bounds of that judgment, especially as it related to Celine’s relationship with Alice. “In the May-December thing, there’s this idea that it must be malignant or injurious to the people involved,” she says. Celine might be someone who harms people in certain ways, but the author says she wondered what would happen “if the judgment of her relationship with Alice was taken out.”

The novel stretches over decades, bringing a reader into contact with each character’s perspective and small evolutions. During that time, the relationships between the women shrink and expand and come to a head. Blakley-Cartwright originally thought the novel should end with a grand implosion. That’s not quite what happens.

“I was happy to leave my characters in a place of harmony,” she says. “It was meaningful for me to see them able to coexist, not with any delusions about who each other are but precisely its opposite, reconciled, for the moment, to the fact of one another.”

The event is free and open to the public. See wellfleetlibrary.org for information. —Aden Choate

Space for Interpretation

The painter Valerie Isaacs has been experimenting with scale. In her studio off Conwell Street in Provincetown, wet paintings dry near a handful that she is in the midst of framing for an exhibition at the Wellfleet Adult Community Center’s Great Pond Gallery. Most of them — including two large landscapes — are of the dunes and other Provincetown landmarks.

“I haven’t shown paintings this big before,” she says. “I’m curious to see how people respond to those.”

A reception for Isaacs will take place at the community center, 715 Old King’s Highway, on Sunday, June 9 from 3 to 5 p.m. The exhibition was organized and curated by Robert Rindler, who was Isaacs’s teacher in his “Contemporary Artists of Cape Cod” class at the Open University of Wellfleet.

Isaacs moved to Provincetown in 2017. She was first drawn to painting on the pier, capturing the colors and reflections of the boats. Her fascination with the dunes is more recent and rooted in the complexity and scale of the environment. “It’s really hard to figure out how to paint the dunes and how all the pieces go together,” she says.

She likes the way time outside immerses her in an ecosystem of light, movement, and transition. “The birds come and sit, the rabbits race around, a few people go by on bikes and in cars,” she says.

The engagement with these landscapes also connects Isaacs to an artistic lineage that includes Charles Hawthorne and Frank Milby, who died last August. “The pier and the dunes are motifs that have been addressed over and over again for 100 years,” she says. “I’ve probably seen a couple hundred treatments.”

Yet the environment still offers her space for interpretation, which she is leaning into during her dune shack residency this week.

The exhibition is on view on weekdays throughout June from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. Email [email protected] for more information. —Aden Choate