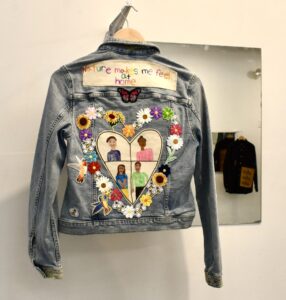

When you walk into the Urvashi Vaid and Kate Clinton Community Room at the Provincetown Commons, you see a collection of jackets and shirts hanging on the walls. The 25 pieces are not exactly garments — not anymore. They were turned into works of art by queer women and women-identifying artists of color.

The works represent artists’ stories about being themselves. “I want people to identify with the stories of others,” says Myra Kooy, the Provincetown artist who curated the show, titled “On Jeans: Embodying Queer Womxn of Color Stories,” which is on view through Saturday, June 8.

“I want to make that happen in ways that are natural and organic,” says Kooy. “That’s why I wanted to use jean jackets. Everyone can identify with jeans.

“These jean jackets are a beautiful canvas,” she adds. “For me, being a Black woman, my ancestors came over as slaves; the jeans material was originally ‘Negro cloth.’ ” She’s referring to the coarse fabrics used not only to clothe enslaved people but to mark them as enslaved.

“This show is a nod to my ancestors,” she says. “When I nod, I nod and say, ‘Thank you.’ When I nod, I reclaim it in a space of joy.”

Kooy made two of the jackets in the show, which she designed for longtime women’s health activists Byllye Avery and her wife, Ngina Lythcott. Kooy sat with them and listened to their stories, then got their permission to create the jackets for them.

For Lythcott’s soft maroon jean jacket, Kooy designed what she calls “a schoolgirl look” on the front. On the back, she included cloth Lythcott brought back from Africa. “Ngina’s jacket is conventional on the front, but what’s on the back is what’s really happening in her world. It’s kind of jazzy,” says Kooy. Symbols that mean patience, loyalty, and family are positioned inside fire-red rectangles and a central diamond.

Avery wanted her jacket to be about her body because she is a women’s reproductive rights advocate, Kooy says. The words “MY BODY” in blue, black, green, and red letters on horizontal white stripes span the jacket’s front. “LOVE” is spelled out down the jacket’s central navy blue vertical stripe. “African colors with the ’70s throwback to finish it,” says Kooy.

Kooy selected the other artists in the show with a local focus, inviting women from the Cape and from elsewhere in Massachusetts. She wants the show to travel to colleges and hopes that LGBTQ women will continue to contribute and can grow the collection. Already, says Kooy, the show includes “a seven-year-old all the way to an 87-year-old.”

Nyanyika Banda is a Malawian-American chef, writer, and entrepreneur. She is the chef at Bread + Roses in Hyannis and the author of The Wakanda Cookbook published by Insight Editions in 2021. A collard leaf is embroidered inside a circle on the back of her vest.

Mixed-media artist Brenda Chapman assembles pieces she’s collected over the years. Kooy says Chapman used to live in Provincetown with her partner before they moved to Staten Island, N.Y. Chapman’s work is geometric. Dark blue patches on her jean jacket are lined with gold and accented with red and bright yellow lines.

Tamora Israel’s jeans shirt sports a pair of colorful headphones on the left pocket. Red and black stars are sewn onto the bottom right of the shirt and the word “life” cuts across the middle in gold. Sky-blue letters spell out “Podcast” across the top.

“Shine usually comes to Provincetown for Women of Color Weekend,” says Kooy. She’s talking about the designer Nikia Manifold, who goes by the nickname a friend gave her 20 years ago. The word “Shine” appears three times on a gold rectangular patch on the lower left side of her black denim button-down shirt.

Mina Stern-Wenk, an artist who has a jacket in the show, will be at the Commons on June 7 for a dance performance to accompany the work. When WOMR asked Kooy if she could do an International Woman’s Day playlist, she asked each artist to contribute a song and say a few words about its meaning. Their song choices and words are included in the show’s pamphlet.

Kooy and artist Jody Johnson installed mirrors next to the garments. Their idea was to show the back side of each piece, says Kooy, “but the mirror made the show sculptural. I realized how a show can be rehung — how craft turns into art.”

Serendipity came into play. “I went into the Methodist thrift store and there was a pile of mirrors — they were $2,” she says. “They were right in front of me.”

Kooy, who is set to open a new Commercial Street gallery, Radiance, wants people to feel something when they come into the space at the Commons. “It’s hard to make a white box room have an energy, but this one does,” she says. “It feels warm. It has to do with the mirrors and the love these artists put into their work.”

Mirrors help viewers see themselves in the work, she says. “You see the jacket, and the people, and the jacket across the way,” she says. “It slows you down. You look a little closer.”