In 2019, when Adam Moss left his powerful perch as top editor of New York magazine after 15 years, he decided to devote himself to painting. It didn’t go well. He was obsessed and tormented with his progress as an artist, and the harder he worked, the more frustrated and unsatisfied he became. To lift himself out of that quagmire, he embarked on a project that would employ his skills as a journalist: he would talk to artists of all stripes and genres and explore how they did what they did so well.

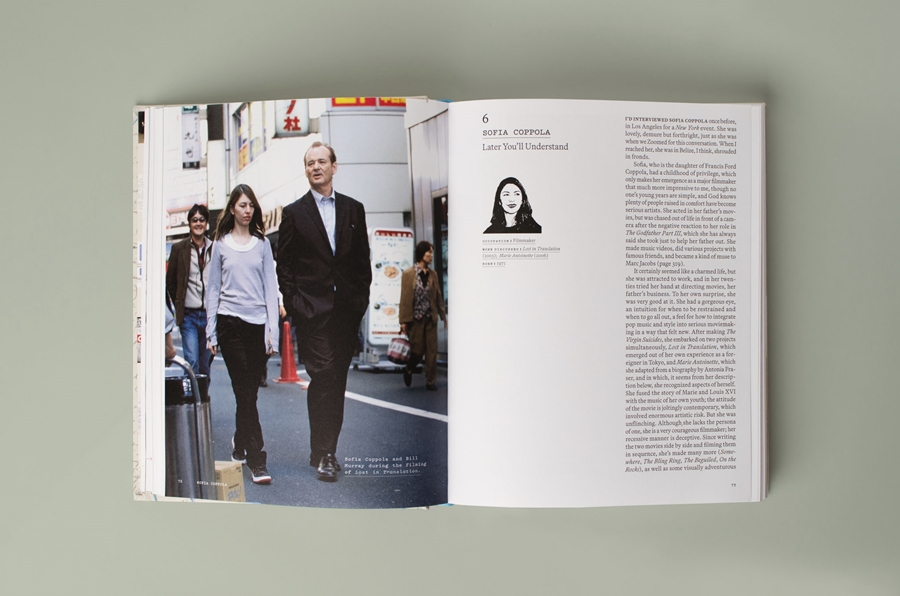

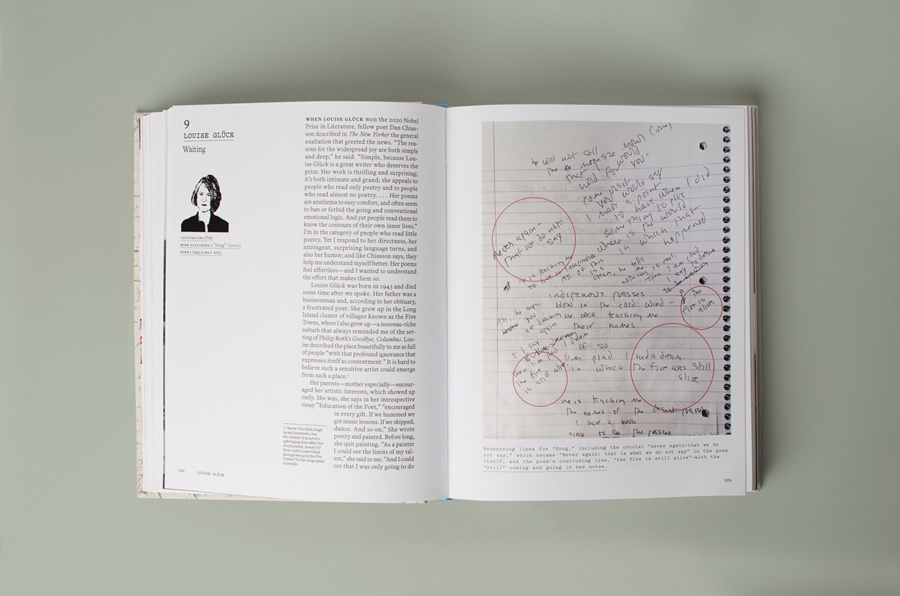

The result is a book, The Work of Art: How something comes from nothing, which was published by Penguin Press in April. It is, in itself, a splendiferous piece of work, filled with thoughtful analysis, joyful and humorous stories, and hundreds of images and doodles and footnotes. The collection of artists’ voices is impressive, even dazzling, reflecting Moss’s diverse tastes: you’ll read about filmmakers Sofia Coppola and Andrew Jarecki, designers John Derian and Marc Jacobs, television series showrunners David Mandel and David Simon, playwrights Tony Kushner and Suzan-Lori Parks, drag performers Grady West and Taylor Mac, poets Louise Glück and Marie Howe, photographers Susan Meiselas and Gregory Crewdson, visual artists Kara Walker and Barbara Kruger, composers Stephen Sondheim and Nico Muhly, and journalists Gay Talese and George Saunders. There are quirky outliers, too: puzzle maven Will Shortz, architect Elizabeth Diller, choreographer Twyla Tharp, radio host Ira Glass. And these are only half the subjects in The Work of Art.

Moss says he considers “process” an ugly word, and his curiosity about what artists do actually runs deeper than that. He wants to know where ideas come from and how they are recognized. He explores how artists motivate themselves and what kind of emotional wherewithal it takes to endure the rollercoaster of success and failure. And, not surprisingly, he wants to know how artists edit themselves — what to preserve and what to junk, and most important, where to begin and when to end.

The 43 artists in the book are profiled in individual chapters that can be read in order or by jumping around. Moss mostly allows the artists to speak for themselves. Some chapters are done as Q&As, some are free-flowing and uninterrupted quotations, and a few are standard profiles in the author’s voice. But in all the chapters, Moss is present: finding connections and lessons in footnotes, introductions, and questions. None of it reads like a textbook or heady criticism; Moss is steadfastly down to earth and self-effacing, even calling himself a “fanboy” when talking to Sondheim. Though Moss’s connections and access are extraordinary, his interest is in sharing his discoveries, not in promoting himself.

Yet the book is surprisingly personal. It’s essentially structured as the journey of one frustrated artist trying to learn from masters. I was acquainted with Moss professionally, as magazine editors in New York City (we were both on the advisory board of Out magazine when it launched) and partially through his husband, Daniel Kaizer, who is a college classmate of mine. Moss’s rise to the top of his field was legendary: he was a wunderkind in his 20s at Esquire, launched the short-lived but influential 7 Days, then helped reconceive the New York Times Style section and became editor of the New York Times Magazine, all before shepherding New York into the internet age.

Pieces of his history keep dropping into the book. Who he is often explains his familiarity with his subjects and his ability to extract choice details from notoriously guarded personalities. The artist Barbara Kruger, for example, created a famous New York cover for Moss that featured New York Gov. Eliot Spitzer, amid his fall from grace with prostitutes, with the word “BRAIN” pointing to his crotch.

Visually, the book explodes with doodles. That’s appropriate for the subject, because many of the artists — especially the writers — collect their thoughts and impressions on piles of scrap paper and in notebooks. But it’s also a trademark of Moss as an editor. 7 Days was noteworthy for its color-coded doodads and segmented copy, and Moss juiced up the stodginess of the Times with his kaleidoscopic taste, offering playful breaks in the swaths of black and white and special issues chock-a-block with collections of short and pungent items. In The Work of Art there are arrows and subheads aplenty; the book itself, with its 43 diverse artists, feels like a special issue of a magazine.

There is also a strong Provincetown connection. Moss and Kaizer own the houses and buildings that surround the historic Hawthorne Barn, and they bought and renovated the barn itself so that the 20 Summers program could be based there. Many of those profiled are Provincetown regulars like designers Derian and Jacobs and writers Michael Cunningham and Tony Kushner. A breakdown of the genesis of Kushner’s Angels in America opens the book. Moss’s interview with Grady West, creator of drag alter ego Dina Martina, is a true find, since West rarely speaks out of character.

Despite assembling, as Moss puts it, a “not particularly rigorous but pretty voluminous dataset” of artists and the ways and means of their creativity, he never arrives at any concrete conclusions. But that wasn’t expected. It’s all about the journey. Artists of all genres and levels of frustration will certainly be drawn to the book, but it’s almost as certain that those who appreciate art but don’t create it themselves will be riveted. As an experienced journalist, Moss knows that learning what’s behind a work of art doesn’t lessen it or your experience — it simply broadens your understanding.