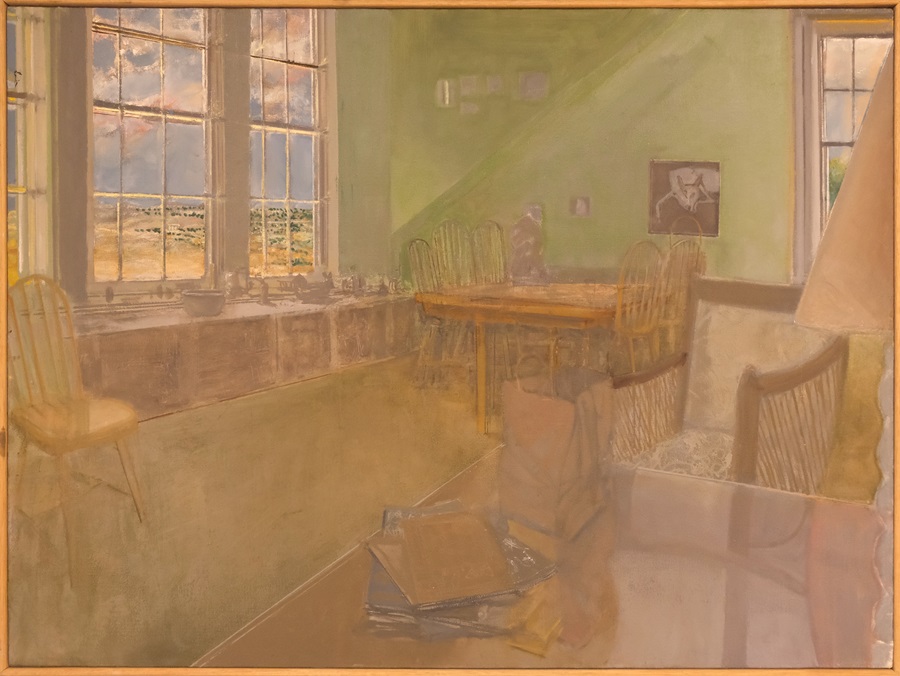

Bob Henry paints all sorts of things but periodically he sets up his easel and paints the rooms he lives in. In these paintings, a few of which can be seen at Wellfleet Preservation Hall, he explores the dialogue between an inner space and the outside. Often the landscape of Wellfleet’s Duck Creek peeks through the windows in his interior paintings.

In Wellfleet, Third Floor he makes a painting of his sitting room, but the real subject here is light breaking through the stormy clouds outside the window and filtering through the room, illuminating ledges and table tops and bouncing across the walls. The burdensome and banal objects of daily life — a pile of papers, a shopping bag, old chairs — are heightened by the transformative experience of light and color.

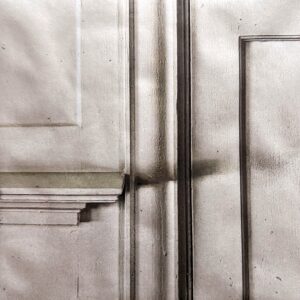

Rebecca Bruyn’s fascination with light comes through in a new body of work in which she photographs the interiors of old American houses and prints them on translucent vellum. “The light enhances the normal everyday things one might not look at when you’re in your home,” she says. In her photographs natural light animates overlooked details like architectural moldings, candle stubs, and curtains. A ghostly atmosphere infuses these pictures, alluding to the histories of the lives that once inhabited the rooms.

Erika Wastrom, an artist who lives in Barnstable and shows in Provincetown’s Gaa Gallery, uses her paintings of interiors to impose order on a less-than-ordered domestic life. The mother of two boys, ages six and nine, she fantasizes about living in a perfectly curated home through her subscription to Homes & Gardens, the British decorating magazine. Her paintings are another form of escape. Mundane objects like a drying rack and more sentimental ones, like a Paul Klee print purchased on her honeymoon are contained in controlled pictorial spaces defined by clean, flat planes of color and passages of expressive patterning.

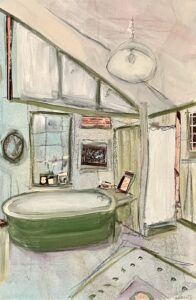

Karen Cappotto has found herself recently fascinated with the interiors of quintessential Provincetown structures, including the dune shacks and the Mary Heaton Vorse house. She made one of her first interior paintings nearly ten years ago after helping a friend move out of a summer cottage on Creek Road. “It was one of those moments where I knew my experience in Provincetown would change,” she says. “I knew our bohemian lifestyle was forever gone.” She memorialized the experience in a 17-foot painting. In Bath Time, a more recent painting of one of the improvisational homes on Tasha Hill, she strikes a tone that is both elegiac and matter of fact in its bare-bones depiction of a bathroom with funky windows. “I’m focused on places that I feel are precariously close to not being around for very long,” Cappotto says.