Sasha Wortzel says that her current work in film, photography, and printmaking is a form of kriah, the Hebrew word for “tearing” that refers to the Jewish practice of rending one’s garments in bereavement. A torn Key West baseball cap she found in the thrift shop at Provincetown’s Methodist Church hangs on the wall of her studio at the Fine Arts Work Center, where she is a visual arts fellow.

The Florida native notes the Key West-Provincetown connection. The hat is a ghostly nod to the effect of climate change on our coastline, she adds.

Kriah also shows up in the strips of torn python skin she was given after filming a mother-daughter hunting team in the Everglades. Wortzel repurposed the shiny snakeskin on two second-hand lawn chairs. Kriah also figures in her photographs of the effects of Hurricane Ian, which ripped through Florida in 2022.

Her feature-length film-in-progress, River of Grass, explores the violence of Florida’s colonial past and the present-day ecological crises of the Everglades through archival images and production footage that she has shot over the past five years.

“These canals, these rivers and chains of lakes here are all Everglades,” says Wortzel as she traces her finger across a map of the state. “It’s just been turned into cities and condos and farms.”

She grew up on Sanibel Island, near the mouth of the Caloosahatchee River. “The water from Lake Okeechobee has been polluted and now is rerouted into this river,” she says. “It ends up in the place I grew up. But it’s also a gorgeous place — 70 percent wildlife preserve.”

Wortzel is based in New York, but her work is about the entire Eastern seaboard. “I travel from South Florida to Riis Beach in Queens, going up the shoreline — all spaces that have shaped me in some way,” she says.

River of Grass reimagines journalist and conservationist Marjorie Stoneman Douglas’s book The Everglades: River of Grass (1947). The book, which has been compared to Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, helped save the Everglades from being drained for development.

Since she arrived at FAWC, Wortzel has been working on the film’s structure: assembling and editing the footage, writing a script, and figuring out how her voice functions in the film.

“This is a big turning point for me,” she says. “It’s the first time I’m putting my own voice into a film. The film is a dive into the Everglades’ past and present to form a picture of what we’ve done to this place.

“This is a massive project about where I’m from,” she adds. “It’s a personal essay film — maybe the most personal thing I’ve ever made.”

In Provincetown, Wortzel wakes up every morning, has her coffee, pulls a tarot card, sets a timer, and writes. “I work for a short block of time,” she says. “When the timer goes off, I walk to the bay and back.”

Her creative process spills out into sculpture, photography, printmaking, and sound. But when the work is done, she always ends up with a film.

“That collective experience of cinema is extremely important to me,” she says. “I think of how cinema can be inside the gallery and how other work can be a companion to the film.”

There is a print shop below Wortzel’s studio at FAWC. “I’ve been going through photographs I’ve taken over the last five or so years while making this film,” she says. “I did a lot of avoiding myself while trying to write it. I’d go down to the print shop when I was struggling with the writing.” Printmaking, she says, helped her develop a physical relationship between her body and the images she was working with.

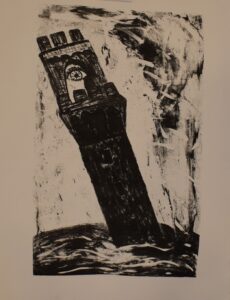

Tower, a stone lithography print of the Provincetown Monument, has a giant eye on it. “To me, the monument is disturbing,” says Wortzel. “It’s a symbol of settler colonialism, and you can’t get away from it. It’s always watching you.”

She describes the stone lithograph process: “You draw on the stone and then use a chemical process to etch the image into the stone, ink it up, and run it through the press,” says Wortzel. “I felt it was important because of the stone of the tower.”

She has one of the few FAWC studios where the monument is in full view. It’s a corner studio with a trapezoid shape. “You can also see the monument from my apartment,” she says. “You go into the woods and turn a corner — it’s still there.”

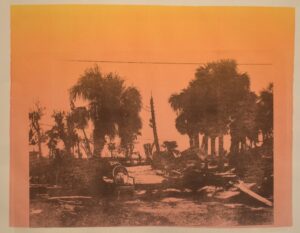

Wortzel’s paper print monotype titled Chair for Marjorie shows destruction in the Everglades after Hurricane Ian. Floodwater pools behind an empty cane chair. A bare palm tree’s trunk rises into the hazy orange sky. The image shows outlines of wreckage, yet most of the tree canopy remains.

“There was a 12-foot storm surge and 150-mile-per-hour winds,” she says. “The entire island was underwater.”

Wortzel graduated with a B.A. in sociology and gender studies in 2005 from New College of Florida, where she researched social movements with Prof. Sarah Hernandez. The college’s gender studies program was abolished last year by a new board of trustees after an overhaul by Gov. Ron DeSantis.

“What’s happening with New College tells a larger story of the political climate in Florida right now,” says Wortzel. “Florida is a microcosm of all the problems in this country. It’s a state that’s trying to erase trans people and Black and indigenous histories from education. That’s an undercurrent in a lot of the work I’m making.

“I’m gay,” she adds. “My parents are hippies, Jews from the Bronx and Chicago, who were activists when they were younger.” Wortzel grew up listening to jazz with her dad, a music lover. Both parents are cinephiles, too. Her mother, she says, knows everything about 1930s and ’40s movies.

Wortzel’s mother took her as a child to feminist bookstores and art museums. “I had access that not everyone has to arts and culture,” she says. “It had a big impact on me and my sister. We also got to be in nature all the time.”

Wortzel’s grandfather was a New York City taxi driver who emigrated to the U.S. from Minsk, Belarus. She paid for her M.F.A. at Hunter College’s Integrated Media Arts Program with some of his taxi medallion money. The program is geared to artists working at the intersections of art and cinema.

Marjorie Stoneman Douglas’s poetry, prose, and short plays about South Florida have heavily influenced Wortzel’s work. She also cites the work of queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz, the poetry of Audre Lorde, Barbara Hammer’s films, and Saidiya Hartman’s idea of critical fabulation. And she says photographer Alvin Baltrop’s work on New York’s Hudson River waterfront and filmmaker Chantal Akerman are other important influences.

Finally, in the spirit of tikkun olam, the Jewish idea of “repairing the world,” Wortzel hopes her films spark conversations, educate, and encourage viewers to think about their relationships with each other. She will be showing parts of her film in progress along with her prints at this Friday’s FAWC showcase.

Repairing the World

The event: A showcase with fellows Rehab El Sadek and Sasha Wortzel

The time: Friday, April 19, 5 to 8 p.m.

The place: Fine Arts Work Center, 24 Pearl St., Provincetown

The cost: Free