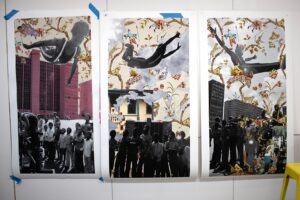

The kids are at play. They’re on swings and trampolines. These contraptions allow them to fly, even if only for split seconds. They’re resisting gravity, getting out from under its thumb. But it is hard to tell if what we’re witnessing is their defiant ascent or the fall that comes when gravity inevitably asserts itself again.

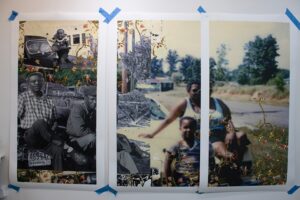

The adults are at leisure. They lean on the railings of their porches and sit on the hoods of their cars.

These images fill nine panels of a massive collage that LaRissa Rogers, a visual arts fellow at Provincetown’s Fine Arts Work Center, has been working on all winter. The photographs of trampolines, swing sets, and cars are in conversation with one another. In Rogers’s hands, which take nothing for granted, they become not everyday devices but astonishing propositions. They transport us across geographies and allow us to transcend time.

“They provide, in a quite literal way, momentary liberation,” Rogers says. “It’s a moment where you’re not grounded, and you’re given a sense of possibility.”

Rogers has culled the images from the online Black Archives project and from her own family photo albums. They span decades and cross state lines, but they reveal uncanny resemblances.

“I was looking for a moment of serendipity,” Rogers says. “I picked this picture, for example, because this boy looks so much like this one, who is a family member of mine.” She draws an imaginary line in the air connecting the two.

The nine panels of the collage are currently in Rogers’s studio on FAWC’s second floor. Some are mounted to the wall with painter’s tape. Others are on the floor, recently fetched from the trunk of her car and still unfurling from having been rolled up. One has a dirty shoeprint on it.

“I’m not very precious about my things,” she says. “I really should be more careful.”

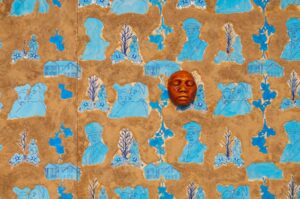

The panels, though strewn about, nevertheless form a coherent visual whole. They’re pulled together by a chinoiserie pattern Rogers superimposed on the pictures. At first glance, the pattern appears to be just a fun splash of color — golden yellow, robin’s-egg blue, and deep pink — but on closer inspection a new reality comes into view.

“This specific chinoiserie pattern is of a hunting scene of these exotic animals,” Rogers says, “and the collage is contrasting that hunting with archived images of Black folks just living their lives and having moments of joy.” Look again and the pattern is not so much framing the people in the photos as it is closing in on them. What at first seemed like beauty now looks more like a threat.

Rogers’s mother is Korean and was born in Seoul. During the Vietnam War, she was adopted by a Black U.S. soldier stationed there and then raised in Virginia.

“The only place where my mom saw herself represented growing up was in the blue-and-white chinoiserie patterns that adorned the plates and tea sets in her aunt’s house,” Rogers says.

That pattern has been a motif in Rogers’s work since her senior year at Virginia Commonwealth University. She graduated in 2019 with a degree in painting and printmaking. Her cohort’s senior thesis exhibition was in an abandoned strip mall. When the group went to choose gallery spaces, they discovered one of the units had blue-and-white wallpaper depicting porcelain vases.

“I immediately said, ‘This room is mine,’ ” Rogers recalls. “It was my mom in that wallpaper.”

Rogers grew up in Charlottesville with eight siblings, five of whom were adopted, and there were foster children as well.

“My parents wanted the house to be a creative space for all of us,” she says. Every summer, her mother would choose a different theme — like “rainforest” or “under the sea” — and they would all paint the basement walls accordingly.

She pursued an M.F.A. at UCLA , and during the first year, Covid hit. She took classes online but lived at her parents’ house without a studio space.

“I was going to protests,” Rogers says, “and having conversations about police brutality and the Stop Asian Hate movement. And, in that moment, I asked, ‘Why am I making something to put on a wall when action needs to be taken?’ ” She shifted to performance art and installation.

“The feelings I was having were completely in my body,” she says, “and I wanted my work to capture that, to be multisensory.” In a 2020 video installation titled We’ve Always Been Here, Like Hydrogen, Like Oxygen, Rogers washes her body with oranges in one clip while in a simultaneous one she gently caresses an orange for so long that it begins to disintegrate.

She is currently painting over the photographs in her collage project with thin acrylic paint. The intended effect is for the photograph to still be visible through the paint, such that the two mediums become blurred. “Painters would say, ‘That’s not a painting, that’s a photograph,’ and photographers would also be upset,” Rogers laughs.

The decision to return to a more traditionally visual body of work while at FAWC was not made lightly. She says, “This project started with thinking about Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Swing,” a 1767 painting considered to be one of the masterpieces of Rococo style. “It was a very over-the-top display of wealth and power. Chinoiserie emerged as a subset of this heavily ornamental style. I’m interested in the aesthetics of excess and leisure. Who has access to those things?”

The idea of adornment comes up again and again in Rogers’s work. She says she’s interested in the ways certain aspects of Black identity “come into being through hair styling and jewelry and decoration” but also the ways in which “Asian people and their bodies have been used as decoration.”

She brings up a passage from Toni Morrison’s Beloved in which Sethe compares the whipping scars on her back to a chokecherry tree. “You got a mighty lot of branches,” Morrison writes, “Leaves too … Tiny little cherry blossoms. Your back got a whole tree on it.”

That passage is a moment of hope for Sethe. “It allowed her to come out of her pain,” Rogers says, “and see it from afar, from outside of herself, as a form of adornment. These keloids can be a grotesque kind of beautiful.”

As she talks about that passage, Rogers walks to the back of her studio, where three sculptures she’s been working on as part of another project are displayed. She calls them “cannibalized tchotchkes.”

Rogers has eBay alerts set up for different 19th- and 20th-century porcelain figurines, many of which are offensive depictions of Asian and Black people. Using these found objects as her starting points, she covers them in more and more porcelain, each layer coming out like a bulbous overgrowth. She creates cracks in the sculpture, and the effect is like an up-close look at flaking skin.

A viewer wavers, unsure whether the sculptures are alluring or disturbing. In either case, it’s hard to look away. Rogers proposes these works as a way to face the violence of our histories. Her art poses the question: “What can grotesque beauty offer us?”

Cannibalized Tchotchkes

The event: A showcase with fellows Adeniyi Ademoroti, Tyler Raso, Miguel Braceli, and LaRissa Rogers

The time: Friday, March 22, 5 to 8 p.m.

The place: Fine Arts Work Center, 24 Pearl St., Provincetown

The cost: Free