PROVINCETOWN — The Mary Heaton Vorse House, at 466 Commercial St., is the informal epicenter of town history. Vorse, a journalist and civil rights activist, spent most of her adult life in the house, from 1907 to 1966, when she died there at age 92. While she was alive, the house was a social nexus, attracting those who shared her interests; after her death, it was a rooming house, recalled fondly by many who stayed there. But Vorse didn’t just live in the house, she literally merged it with her own identity. In Time and the Town: A Provincetown Chronicle, her 1942 memoir, Vorse devotes an entire chapter to her house. And now, in 2020, a house built in 1850 is becoming an icon of the town once again.

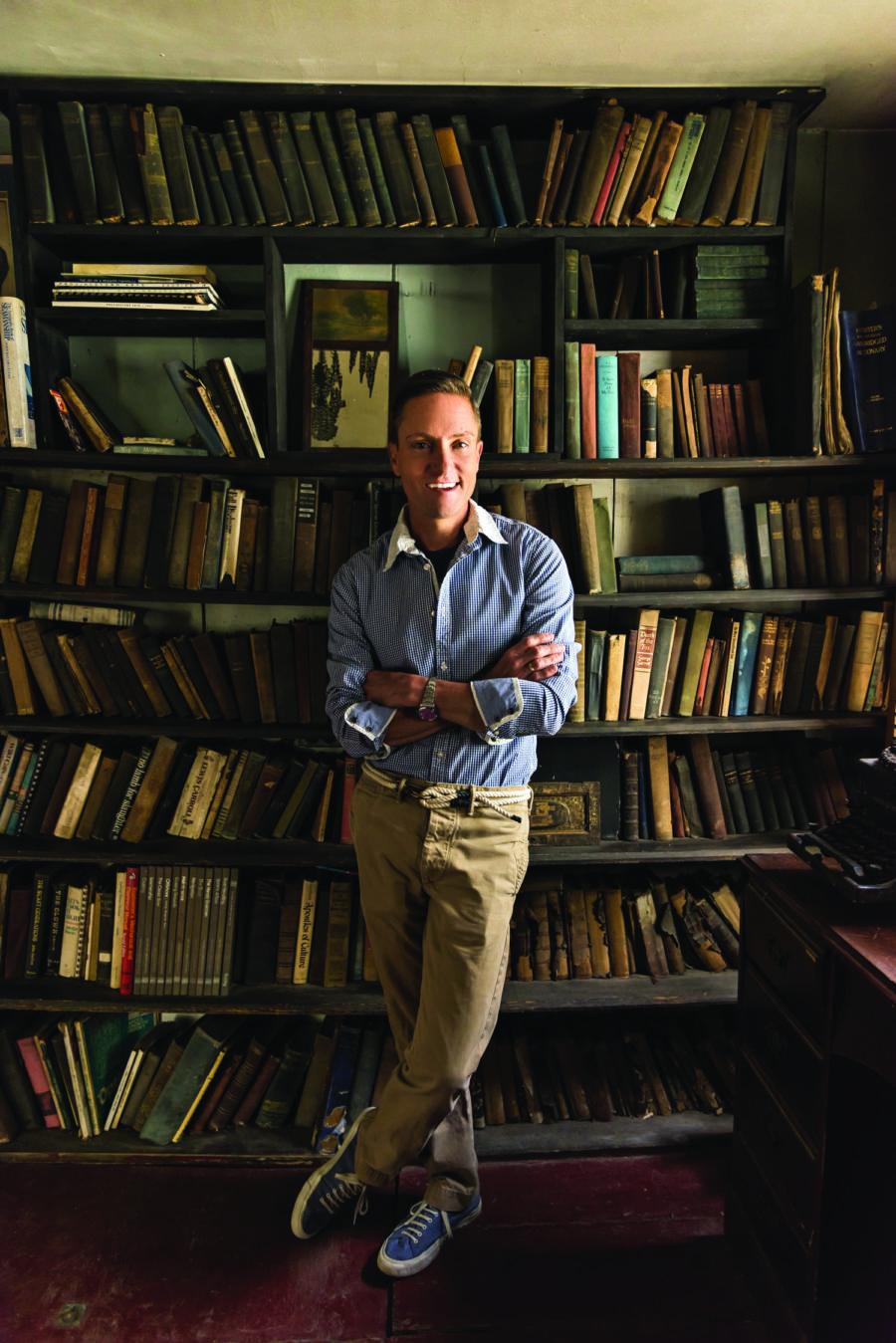

San Francisco-based designer Ken Fulk and his husband, Kurt Wootton, bought the house from Vorse’s descendants in June 2018. They live across the street, at 471 Commercial, in the house that was the late George Bryant’s, which they restored. Fulk, a master of historic preservation, is now meticulously restoring the Vorse house, which will become a resource for the town, its citizens, its institutions, and its devotees.

Last week the Independent set up a conversation between Fulk and journalist David W. Dunlap, creator of Building Provincetown, to learn more about the project. Their dialogue reflected the passion both men have for this unique and invaluable place and its history.

Fulk described progress on the restoration. “We have finally, over the past six months, kicked into high gear,” he said. “It will be done in May. I couldn’t be more excited. We will have spent much more money on the house than we did across the street, which is the irony. And it’s going to look like we didn’t do anything!”

“Who is your contractor?” Dunlap asked.

“Nate McKean,” Fulk said. “People call him Nate, but his mother only calls him Nathaniel. He grew up in Provincetown and went to Provincetown High School. He had a girlfriend in high school, Bronwyn Jackett. They went other directions; now they’re getting married in June. Nate is an amazing craftsman. He understands Provincetown — the handmade houses, the use of salvaged materials.”

Dunlap noted Fulk’s way of taking time to meet people in town and listen to them respectfully. “You have honored George Bryant in George’s own house with a beautiful portrait by Mischa Richter,” Dunlap said. “As if to say that this is his place. So many washashores insulate themselves. You have just opened his place up. No alarm signs and hedgerows.”

“Why be in Provincetown if you’re going to isolate?” said Fulk. “I would lose why I’m here.”

Fulk’s openness led to the Vorse House project.

“Mary Heaton Vorse’s granddaughters approached us,” he said. “They said, ‘We’re thinking of selling the house. Someone told us you might be the right person. We are concerned that someone is going to destroy it.’ That’s how it began. They came to the Bryant house, we had dinner, we had lots of talks. They’ve become dear friends through this process. And they knew that I wanted nothing but to love the house and to return art and artists to it.

“I want to remind folks who buy houses,” Fulk continued, “that one of the greatest assets we have is the architectural integrity of these houses, not just the exterior but the interiors. I happen to be in a position where this is what I do for a living. Maybe people will pay a bit more attention to it through me. That was the initial idea — we wanted to save this house, because I’m 99 percent sure that if someone else had taken it, it wouldn’t be preserved. We couldn’t afford to lose that house and what that house represents. I’ve read Time and the Town dozens of times. I keep it by my bedside. I give it to every person I come in contact with who has never read the book because it so aptly describes where we’ve been and, frankly, who we are.”

“Let me jump ahead to May,” Dunlap said. “What will the layout of the rooms and various spaces be?”

“The house is laid out pretty much as Mary Heaton Vorse had known it,” Fulk replied. “We subtracted a bit, but we really didn’t add anything. We did a little archaeology, opening up the space. You’ll still enter from what was then Mary Heaton Vorse’s library. And we have all the ephemera and books, and Heaton’s typewriter and Mary Vorse’s hat, which will go back into that space.”

“Great!” Dunlap exclaimed. Heaton and Mary were Vorse’s children.

“We have four new fireplaces in the house,” Fulk continued. “We had to rebuild all of them. We restored the door from the dining room that opens and lets the sea breeze in. Some of the windows were able to be restored, but many we had made by hand, with the single pane, using the old glass. All the floorboards came up and were numbered, and are now going back down, because we had to put in a new foundation. New systems have been put in place — plumbing, electrical, heating. All of the bathrooms have salvaged plumbing in them. We have seven bedrooms. The one real change is in the very back, which was the newest part of the house. That entire lower section had to be rebuilt. It was poorly constructed, probably in the ’40s, ’50s, ’60s. It was rotten and not worth saving.”

“To what use will all these spaces be put?” Dunlap asked.

“We want it to be a community asset to help support arts organizations. Whether it’s PAAM, or the theater, or the film society, or Twenty Summers, or the Fine Arts Work Center — the list is long. There’s a place for all of them.”

“What are you permitted to do with the place under town rules?” Dunlap asked.

“It’s a private home — it’s no different from my house across the street,” Fulk said. “If someone stayed there, they’d stay there as our guest. What that allows us to do, hopefully, is fill it with guests from Twenty Summers when they come — we already have a couple planned. We’re going to do a residency with PAAM; we’re going to do a residency with the film society; and with the theater, when we host the annual American Playwright Award. We want to support the culinary traditions of Provincetown and recognize that as one of the arts. We’ve befriended folks who work in sustainable agriculture and who live and breathe the farm-to-table idea of eating and growing locally. We will make sure that that is part of the experience of the Vorse House.”

“You’re creating something without much of a model,” Dunlap said, “and taking time to let it be what it wants to be.”

“We bought a house, and we’re trying to be great stewards,” said Fulk. “We’re going to fill it with good people. We’re going to pay the bills. Right now we’re taking a bohemian, relaxed approach to all this. It will be a very Provincetown moment of just opening the doors and allowing the community to come in. I don’t know what success looks like yet. Currently it’s been enough just to get the house back. Maybe in five years, it’s taken on a life of its own, and we start a foundation and have to hire a director. When I leave the planet, the house will go to one of these organizations with, hopefully, enough money to maintain it. And people for generations past me will get to experience the house.”