There are 50 galleries listed on the Provincetown Office of Tourism’s website, and that list doesn’t include the walls of the town’s museums, artist studios, hotels, inns, and boutique shops that also function as retail spaces for art. Despite the abundance of primary art market selling spaces, there is only one auction house in Provincetown.

The Bakker Gallery and Auction House is tucked into the back of an alley at 359 Commercial St.

“You’re a newbie, right?” Spencer Keasey asks a reporter in the front room of the gallery. He is standing in front of two paintings and holding a blue clipboard. “My gut reaction is 6 to 8 start 3, but we’re going to do 8 to 12 start 4,” he says. This is auction talk.

The two paintings had been brought in by Bill Doriss, a vendor at the Wellfleet Flea Market. Doriss says “stuff” just comes to him. He trolls the thrift shops and estate sales for items to consign at Bakker. “They reject my stuff, mostly,” he says, “but if they take it, it’s going to sell.”

Today, Keasey has decided to bite on one of the paintings Doriss brought in to consign. “I did it because it’s beautiful,” he says.

Ten years ago, auctioneer Jim Bakker and Keasey were both between jobs and decided to open a gallery specializing in historic Provincetown art. Bakker made Keasey the director.

Bakker had started out in the 1970s by opening an antique art gallery on Charles Street in Boston. He says he drifted in and out of storefront retail sales until 1984, when he moved back to Cambridge and opened a gallery at 370 Broadway. A year later, he started doing auctions out of that gallery space.

One customer who attended Bakker’s auctions in Cambridge was Provincetown collector Anton “Napi” Van Dereck Haunstrup. “Little by little, we started selling some important paintings from Provincetown,” says Bakker.

Napi persuaded Bakker to do the consignment auctions at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, which he has done every year since 1988. He opened a summer gallery in Provincetown in 1993.

“I broke even and got to live here all summer,” he says.

He moved to Provincetown full-time in 2001 and continued freelance art appraisals and private sales with his inventory. From 2006 to 2011 he also worked as the director of the Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum.

After he left the museum, Bakker started doing monthly auctions at the Provincetown VFW. “They were fabulous,” he says, “paintings and small furniture, accessories. We sold the remains of painter Gerrit Beneker’s studio that summer.” Beneker was one of the founders of the Art Association in 1914.

Bakker holds the auction record for Beneker’s work after his Self Portrait sold for $22,500 this past summer.

Self Portrait is a 23-by-18-inch oil on canvas. In the painting, we see Beneker’s freshly shaven face and plump pink lips juxtaposed with his furrowed brow. His suspicious right eye is fixed on the viewer. Cracks in the 108-year-old painting only deepen its effect.

The painting has been sold by Bakker twice. In 2021, it was consigned by Beneker’s family and sold for $1,400. But the client who bought it reconsigned it this past summer, and a bidding war ensued.

“Sometimes at auction it only takes two people who really want something to drive the price up,” Bakker says.

Another bidding war took place in 2020 over Ice House Beach, a small oil painting by the late Provincetown painter Nancy Whorf. Keasey estimated it would sell for $2,000 to $3,000, but two bidders drove the hammer price to $27,500. “There are no cut-and-dry answers with any of this,” says Keasey. “All that happened that day is we got two people with deep pockets and egos.”

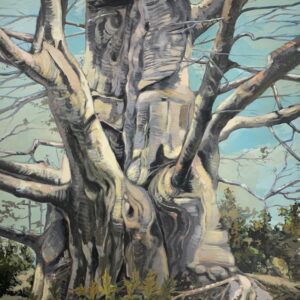

“When Joseph Edwards Alexander died, the family didn’t know what to do with his work,” says Keasey. Edwards Alexander was a gay artist from New Bedford who had connections to Provincetown. A dealer bought his work from the estate, and the paintings are now creating auction records. Alexander’s oil painting The Tree sold for $12,000 at Bakker last summer.

“This all happened because this dealer consigned them in order to establish a market,” says Keasey. “We establish a market, and in turn the artist gets a legacy.”

When Bakker Auctions started, there were some gallerists who thought they were destroying the art market in Provincetown, says Keasey. He says that he tries to bookmark auction estimates right around the artwork’s retail value.

“The estimate is a guideline for what the piece is worth,” he says, “but estimates can frustrate a living artist.”

Bakker Auctions sets price estimates and a starting bid for consigned works. Closing bids are recorded, “but there’s also a buyer’s premium, which is how an auction house makes money,” says Keasey. “A person consigns a piece of artwork to us, and we take 25 percent of the hammer price. But I can’t run a business on just 25 percent of the hammer.”

Keasey says the gallery used to be the primary business and auctions were held only three times a year. “It was old school,” he says. “We had 125 lots per auction at the Harbor Hotel. The auctions were a grand old event.” He would load everything into the hotel while breakfast was served.

Then Covid hit, and the Harbor Hotel was sold. Auctions now take place online and have taken over the larger portion of the business, with five auctions per year. In-person viewings are held in the small back room of the gallery.

When a consigner brings in a painting, Keasey researches the retail price of the piece. “First I try to find out what price the artist would be retailing this for if it’s a living artist,” he says. “The next step is to see if the artist has any recorded sales on the secondary market.” Keasey uses an auction house database called AskArt, which tracks more than 300,000 living and dead artists.

When a client wants to consign a piece but the artist has no recorded sales on the secondary market, then, “That’s hard,” Keasey says, “because I think, well, I don’t want to offend anybody. Right? It’s all about relationships in this town. But we only get to sell about 750 lots a year.”

Even if the hammer price is less than the retail value, having a recorded sale in an auction house is important for an artist’s legacy. “If an artist’s work isn’t recorded anywhere, hypothetically, the value could be zero,” says Keasey.

“Say you spent $6,000 on a painting at retail,” he says. “The artist has gotten three. Now you want to sell it, right? And you come to me, and you’re like, what can I sell it for? You say, ‘I want my money back.’ You’re rarely going to get your money back. I’m sorry, honey. It just doesn’t work that way.”

Keasey gives conservative price estimates to consigned works. They can get bid up at auction or not get bid on at all, especially if Keasey sets the starting bid too high.

He says primary market retail prices are based on what gallerists think a piece might actually be able to fetch. The secondary market is the “reality check,” he says. “Unless it’s a name like Charles Hawthorne or Motherwell, Provincetown art does not appreciate.”

“People are fascinated with that,” says Bakker. “Buying something that might appreciate and might not.” He says the trajectories of some works are more obvious than others. “I would have never dreamed of some of the modern art and where it’s valued today from when I started looking at it 50 years ago,” says Bakker of artists like Hans Hofmann and Keith Haring.

“Auction records,” he says, “are a recording for history. If your gain is cerebral and you like what you have when you’re looking at your walls, then great.”

“As an artist, you look at your death and think about your work not only in financial terms but in terms of its longevity,” says Keasey. “What do you want to leave behind? You don’t want to leave behind a studio where someone’s going to come in with a dumpster and dump it all.”

He advises artists to sign and date their paintings, get into shows, and create auction records. “It creates a timeline for when you’re dead,” he says. “You have to create some structure about what happens with your work.”

“How do you value art?” Bakker asks. “It’s a great question. It’s subjective. But if you buy what you love, you can never go wrong.”