It was just after 5 p.m. on Friday, Aug. 5, 1977, when Mark Adams and four other firefighters from the National Forest Service spotted a lightning storm coming in off the Pacific Ocean toward the wilderness of the Santa Lucia Mountains on California’s Central Coast. The crew drove up the ridge and saw a bolt strike, followed by billowing smoke from the canopy.

Adams spent that night running along a dirt fire road with drip torches of kerosene, starting fires in the brush to try to contain the spread of the fire surging uphill. The Marble Cone Fire was the largest wildfire in recorded California history at that time. Ten days into the fire, Adams finally got to take a shower.

“The fire experience was double-edged because it was demeaning and thrilling at the same time,” Adams says. “It made me realize I wanted to do science in the field.”

Adams became a coastal geologist. But most people in Provincetown know him as a painter.

“My paintings are meant to use the old visual languages to talk about migration and climate. And to sanctify the people on the move,” Adams says. He paints bodies in motion, recalling what he learned about the figure as a gymnast in college at the University of California, Berkeley or later while doing odd jobs for the Boston Ballet, where his brother David was a dancer.

Adams has taken a circuitous route to Provincetown. He is from Chicago. He stayed at Berkeley after college to take graduate courses in landscape design, which led him east in 1987 to work as a planner on Martha’s Vineyard. A job documenting forest history at the Mass Audubon sanctuary in Wellfleet brought him to Cape Cod.

“When I came to the Cape, it was really important to be able to connect to a gay community for the first time in my life, particularly in the AIDS era,” Adams says. In 1992, he lost his brother David to AIDS.

The National Park Service hired Adams in 1991. “It was the dawn of computer mapping,” he says. He recalls trying to sound convincing about his knowledge of technology. Fortunately, he adds, “My new boss said, ‘I don’t understand it. Just make yourself useful.’ ”

Adams became a cartographer at the Cape Cod National Seashore using geographic information systems to map coastal geology.

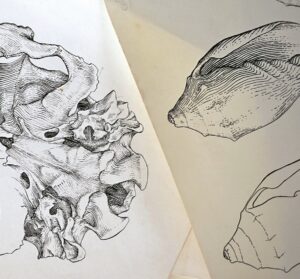

His work has always involved observing and recording the world around him. Adams has sketched fish using a binocular dissecting microscope for ecological analysts, drawn wildfires, mapped the ocean floor, and made studies of the coyotes he has met in his 30-year career with the Seashore. His first show at Schoolhouse Gallery was in 1999.

After 25 years living in a rambling old house in Truro, Adams moved to Provincetown in 2022, where he is a restless inhabitant, his energy green and endless.

One minute he’s walking his bike down Commercial Street chatting with a local innkeeper, the next he’s at town hall in a meeting of the coastal resiliency advisory committee, of which he is a member. He emerges with this on his mind: “Did you know that the Anatolian fault suddenly slipped all at once instead of deforming over 10 million years?” Then he’s off again in his orange backwards baseball cap, leading students or poets on a walk through the parabolic dunes, where “every dune is a slowly moving wave being pushed by weather and water.”

Serving on the town’s conservation commission, Adams says, gives him a role in safeguarding the wetlands here. He points out that Massachusetts was the first state in the nation to adopt wetlands protection laws in the early 1960s.

He is also a board member at the Provincetown Commons. And this year he became the first-ever “scientist/artist-in-residence” at the Center for Coastal Studies.

“I used to go for runs after midnight when I couldn’t sleep,” Adams says. Now he finds time, mostly after dark, to work in his studio on Miller Hill Road, sketching seagulls and portraits of locals he’s met on one of his late-night stops for coffee at Spiritus.

Memories and dreams of the natural world are often his starting points for paintings. “It could be a memory of being underwater or alone on a trail or being surrounded by a massive flock of birds,” he says. “I usually start with a furiously physical sketch, the bodily action of painting. I let my hand lead my brain.”

There is something visionary in the worlds Adams renders in his paintings. And that vision is often big. He brings out a 30-foot-square floor map of the coastal zones around Georges Bank to talk about how the sands of Cape Cod are still shifting after 20,000 years.

Currently Adams is working on a mural for the sea wall in front of MacMillan Wharf. He wants it to show Provincetown’s 10-foot tidal range in the context of storm surges and sea-level rise. He envisions the work extending around town using colors to show where flood levels could reach.

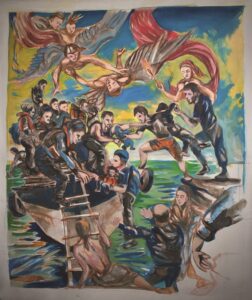

The relationship between humans and climate was more pronounced than ever in the works Adams showed last summer at the Schoolhouse Gallery in which bodies navigate a fluid natural world.

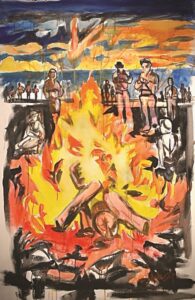

Fires still light up Adams’s work. In Beach Fire at the Bay, he renders a sky at sunset with clouds that resemble wildlife in acrylics and pastels. We see the outlines of figures, their forms reflecting or emitting the light around them. In the foreground, a blazing fire asserts nature’s potential for destruction.

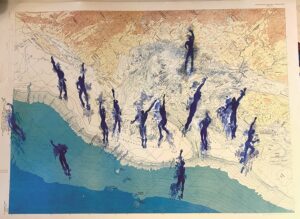

In A Map Painting, No. 2, using inks, acrylic, and graphite on paper, Adams depicts triumphant gliding figures crossing the natural barriers of land and sea along Georges Bank and into the northeastern United States. The figures emerging from the ocean could be signaling sea-level rise, their blue arms reaching out and overtaking the shore. Or maybe they are migrants reaching across borders claiming a shared world.

“Human migration responds to stressors,” Adams says. “People are pushed by war and power struggles and famine and weather.” Adams knows political conflict often has environmental underpinnings and that we need to be open to people’s need to move and live.

Drawings, journal entries, paintings, sketches, maps, interviews, and writings by artists who have close ties to Adams are collected in his 2017 book Expedition. In it, he offers instructions for daily adventures in the natural world: “Let the house flood. Days go by. You begin to understand the moon and the tides as all crabs do. The mail piles up.” His advice is to read the field guides to a faraway place, build a diorama, study the artists, and to pack and go.

Adams teaches sketchbook journaling classes at the Fine Arts Work Center every summer where he instructs students to hold shells, bones, and leaves as they draw them. Then they venture into the dunes to draw the landscape. The writer Michael Cunningham was a student of Adams’s and wrote about the experience in Expedition.

His words seem to capture the problem that propels Adams himself: “It seems that the world — everything and everyone in it — is not clearly outlined, as I might have imagined when I first attempted to draw the skull.”