Jo Sandman wanted a more progressive art education than Boston could offer her. Born in Newton in 1931, she had studied art since she was a young girl, but it was all figurative painting. In 1951, while still a student at Brandeis, Sandman went to North Carolina for the summer to study at the avant-garde Black Mountain College.

The following year, she came to Provincetown to study at the Hans Hofmann School of Painting. She returned almost every summer to vacation with her husband, Robert Asher. She appeared in solo exhibitions and group shows at galleries in town and developed a deep friendship with the painter Robert Motherwell. Now 92, Sandman lives in Lexington and maintains a studio space in Somerville.

It was at Black Mountain, where she first met Motherwell, that Sandman picked up the interdisciplinary mode of working showcased in the current exhibit at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum. Curated by Christine McCarthy, the show consists of a small but illustrative cluster of Sandman’s works that were donated earlier this year to PAAM’s permanent collection. The pieces were sent to PAAM before being catalogued, and McCarthy is currently working with Katherine French, curator of the Sandman Legacy Project, to supply dates and create a chronology of the master craftswoman’s career.

The goal of the project is to display Sandman’s lifetime of creative work at museums throughout the country. French has arranged donations not only to PAAM but also to the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, the Ogunquit Museum of American Art, and the Black Mountain College Museum. The 31 pieces in PAAM’s collection speak to Sandman’s impressive range.

As you walk through the show, you move with Sandman from collage to abstract painting to photography to the written word to pieces that combine all these elements.

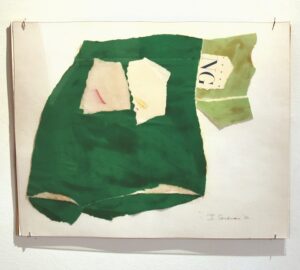

In Torn Paper Collage #2 (“NG”) from 1966, a large grass-green piece of paper takes up most of the surface. A fold at the bottom of the torn paper reveals its true color, faded white, making it clear that the green is just a layer of paint. Two unpainted pieces of torn paper have been pasted over the green piece, looking like the whites of eyes. Uniting all these elements are the jagged and irregular edges of each shape, the mark of Sandman’s hands.

Sandman’s abstract collages are from the 1960s, but she continued to work in collage throughout her career. These earlier abstract works show an affinity for experimentation, shape, color, and found materials. They were precursors to her work with folded fabric in the 1980s and 1990s.

In her large abstract painting Libel, Sandman uses acrylic on canvas to send us into a deep consideration of shape, color, negative space, and line. The three grass-green bars could have been painted with the same paint as the torn paper collage, but the painting is undated.

The relationship between Sandman’s works on canvas and her collages runs deeper than mere hue. For a long time, at the beginning of her career, Sandman only painted on canvas. She left that practice behind for more abstract work with found materials. She was so done with painting that she stuffed many of the canvases into garbage bags that she would bring out only when she needed inspiration.

As the exhibit delves into her photographic work, from a later stage in her career, Sandman’s thematic use of bodies — particularly her own body — becomes clear. In Cluster, a photogravure print from 1992, we see a negative of bent and twisted automotive parts. Their shadow shapes come alive in the print and make them look like an assemblage of the limbs of dancers on a stage. Below the print is an exhibit of the actual automotive tubes in the image.

In a gallery talk in 2022 at the Black Mountain College Museum, Sandman said that, when she went to buy the automotive parts, the mechanic looked at her strangely and asked, “Why on Earth would you want these?” Sandman responded, “I put them in the studio and let them gather energy.”

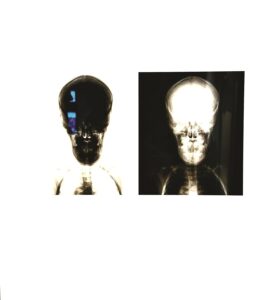

Her works from the 1990s dealt primarily with mortality, represented by the human skeleton. Sandman documented the state of her own figure as she struggled with arthritis. In Transmissions, a collage in acrylic, a circular grid radiates from the image of a skull on a field of translucent yellow. Words are superimposed on the skull form poems in four loose columns. They can be read them horizontally or column by column.

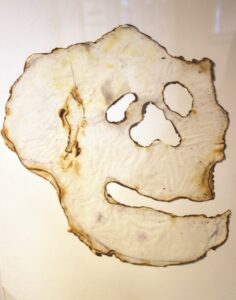

In Skull, Sandman has once again torn paper to create the shape we see, drawing cutouts for eyes and nose. This work is less abstract, a straightforward skull, though not anatomically accurate.

In Positive/Negative, Light Memory No. 33, a black and white version, ed. 4/20 from 2006, Sandman presents two altered X-rays of her own skull viewed from the front: the original X-ray image is paired with a negative version. The negative looks as if her skull has been picked up out of an oil spill or a pool of ink that seeps through the canals of her bones. We are able to witness the state of her body with her.

Hanging next to the X-ray work is Echoes From the Garden, a wood collage on panel. Put in context and conversation with the X-ray, it is equally haunting. Two cut wooden nubs, one black and one bone white, stand out from the white background board. The collage reflects Sandman’s proclivity for breaking her own pieces down into simple abstract forms that increase the drama of a work. One thinks, in the metaphysical sense, of the contrast between light and dark.

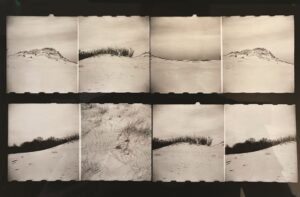

In Dune Scenes, one of the few works that depict the Cape’s landscape, two rows of dune photographs are laid side by side in what look like film rolls. The dunes in the images read like gestural drawings — we can see arcs of black beach grass lining their curves like eyelashes. The changes in the wind’s direction on the grass add subtle variations.

Sandman makes clear that the natural world, like her own work, is full of rhythm, repetition, and bold contrast, sometimes all at once. Sandman once said, as quoted in the show’s catalogue, that photography allowed her to speak “to the tentative nature of life” and “our limited time on Earth.”

Though she made plenty of photographic works, Sandman did not consider herself a photographer. In the same way, a critic once called her “a painter who doesn’t paint.” She worked in so many mediums it’s impossible to clearly define her other than as an artist. She used what was at hand. She used her own life. She collected the pieces in her studio and transmitted the energy they gathered there.

A Painter Who Doesn’t Paint

The event: Jo Sandman, Works From the Permanent Collection

The time: Through Jan. 14, 2024

The place: Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 460 Commercial St.

The cost: General admission, $15