Christine and Michael Jones first encountered Truro artist Nancy Ellen Craig in 2010, five years before she died. After meeting them at the Cape Cod Museum of Art, Craig invited the couple for a studio visit. “We hit it off immediately,” says Christine.

A common interest in cold-water swimming served as an initial bond between the Orleans couple and Craig. As their friendship deepened, Christine, a poet and therapist, and Michael, a visual artist and intellectual property lawyer, became fascinated with both her body of work and life story.

Christine and Michael have now coproduced a 15-minute film, directed by Sarah Hachey, on the life and work of Nancy Ellen Craig that will be screened at Orleans Modern Art and the Provincetown Film Festival. The Orleans gallery is also showing a selection of her large-scale narrative paintings and more conventional portraits from earlier in her career.

“We knew Nancy; we love Nancy,” says Michael. “We didn’t want her memory to just die off without any continued recognition.”

Her large paintings are grandiose in scale and subject. Two pieces in the exhibition depict dramatic events of the early 21st century: 9/11 and the torture of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib. Other paintings explore mythological themes, including a water scene with flailing nude figures and animals. Preston Carter, the great love of her life, is presented regally in two life-size paintings.

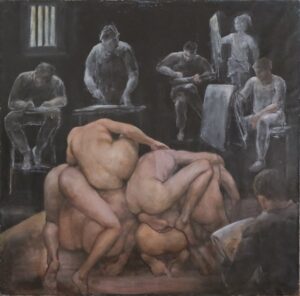

The film’s title, Daughter of Rubens, refers to Craig’s nickname. “Right away I thought there was something unusual about this person that was drawing like Rubens,” says Rob DuToit, a Truro artist interviewed in the film. “People don’t do that anymore, and among her friends we referred to her as the daughter of Rubens … which of course she loved.” Like the 17th-century Baroque painter, Craig had a penchant for the operatic and a virtuosic facility in describing human anatomy, as evidenced in her Abu Ghraib painting.

In this painting a pyramid of naked bodies is based on the well-known disturbing image of the Abu Ghraib atrocities. The figures are rendered with a keen sensitivity to anatomy and line. They are bodies that pulsate with color and life despite their violent and humiliating positioning. This is a 21st-century version of work common in art history, where atrocious events were captured in sensuous detail. Rubens’s Prometheus Bound is a classic example: an eagle plucks flesh from Prometheus’s writhing torso, rendered in over-the-top flourishes of detail and virtuosity. Craig seems to comment on this disconnect in her painting. The human pyramid is surrounded by artists, lifelessly rendered in black and white, sketching the bodies. They are dispassionate observers, mining a tragedy for the sake of beauty.

Craig’s devotion to art was absolute. “The rest of her life rotated around her painting,” said Michael. In the film, Cherie Mittenthal, an artist and director at Castle Hill in Truro, comments on how Craig always “stunk like turpentine.”

“She couldn’t have been anything else other than an artist,” Mittenthal says.

The film discusses her abandonment of her two sons, whom she left with their father when she met Preston. One son, Craig Nelson, who is interviewed in the film, relates memories of beating on the door of her studio as a child and crying when she would not let him in. Ultimately, though, he offers a gracious opinion of his birth mother, with whom he reconciled toward the end of her life. He is now the executor of her estate, overseeing her paintings, most of which are kept in an Eastham storage facility.

Like her paintings, Craig’s life was dramatic. Born into a wealthy family in Bronxville, N.Y., she found success as an artist early in life. She was in demand as a portrait painter for the rich and famous, including Frank Lloyd Wright, the Guinness family, the Duke of Argyll, and Sean Connery. A portrait in the Orleans exhibition, painted in 1952, of a black woman in a yellow dress shows her raw talent as a portraitist. The sensuous light recalls the work of John Singer Sargent, an artist to whom many compared Craig early in her career. The woman looks downward, caught by Craig in a pensive moment. After meeting Preston, Craig continued to travel around the world with him painting portraits on commission, but by the early 1970s they had moved to Truro, where their life took a more reclusive turn.

In the two paintings of Preston, he is represented as a central figure. In one black painting he stands dressed in a yellow tie with his hands on the lapels of his coat. His white hair circles his head like a halo. His gaze is distracted, as if he’s caught up in his own thoughts. In another painting he sits on a chair in a self-satisfied pose. A book is open on his lap as he looks directly at the viewer. In the background, a painter, perhaps Craig, works on a canvas. A painting within the painting depicts a larger-than-life male torso in a cruciform pose. It’s a complex painting, ripe with psychological implications.

The film introduces Preston as an enigmatic and eccentric character: a voracious reader, a hoarder of books, and a writer who never published. He held powerful sway over Craig’s life until he died in 2007. His death and the destruction of Craig’s house by fire paved the way for a new chapter in her life and a greater integration into the Truro community.

Regarding the legacy of her artwork, Michael Jones says she was always indecisive. Many of the paintings are battered — the result of not being properly cared for, or of being transported on top of the black Mercedes that she and Preston owned. She let her early glittery career expire without much regret.

“She only lived for the day,” says Michael. “When Nancy stood in front of a canvas she went to a different place.”

“ ‘Vissi d’arte, vissi d’amore’ was a motto she loved to quote,” says Christine. “I lived for art, I lived for love.”

Daughter of Rubens

The event: Documentary and exhibition on Nancy Ellen Craig

The time: June 17-28; opening reception Saturday, June 17, 5 to 8 p.m.

The place: Orleans Modern Art, 85 Route 6A

The cost: Free